Let’s try to talk of Amma AriyanAmma Ariyan can be watched on Potato Eaters Collective’s YouTube channel., a film that is about nothing in particular.

On Page 21 of a particular edition of Arun Joshi’s The Apprentice (1974), the hitherto unnamed protagonist describes for the titular apprentice—a proxy for the reader—a remarkable event from his ancient, long-spent youth. In the said scene, the protagonist, overcome by the desire to join the ranks of Subhash Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (INA), neglects the pleas of his mother, mounts his bicycle, and embarks on a journey that will help him fulfil a personal delusion. At a certain point within this telling, his tone begins to falter. Overcome by emotion, he registers with the reader a confession, “…and then, suddenly, quite without warning, all had turned to ashes, dust and ashes. All of a sudden I knew that I could not go through with it. Each succeeding mile, my courage dropped another notch until finally, sweating and exhausted, in sight of my destination, I sat in a mangrove and wept.”

The noticeable feature of the scene is the time that it takes for the protagonist to arrive at a point of personal exhaustion. In effect, he cycles continuously for two days before an abrupt apocalypse befalls his chosen purpose—it is then that he can, as he says, no longer go on. Here, movement in itself is rendered totemic—in this, like in the cinema, space is employed as a means by which to account for the passage of time. As he continues to cycle, to move, from his home and towards his chosen destination, the protagonist allows for the potency of his original, revolutionary intent to undergo a natural decline. Disillusionment is verifiable not by the crumbling of the spiritual edifice itself, but by debris left behind once the siege is over.

I.

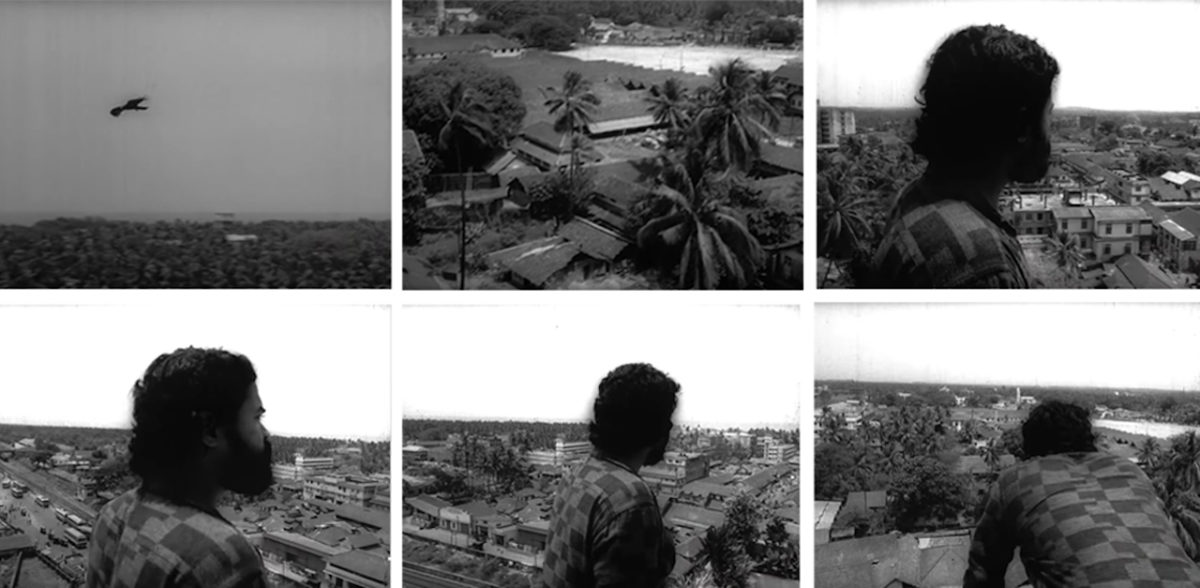

John Abraham’s Amma Ariyan (1986) rests uneasily between sequences of a similar, temporal deflation; in essence, between two sequences that germinate from a specific intention, but by the time they conclude, are rendered devoid of meaning, symbol, insight, or intent. The first documents the aftermath of the discovery of a tragic suicide: a young tabla-player named Hari—problem-child, a lost soul, a would-be revolutionary—has hung himself from a tree atop a hill, and his compatriots gather resolve to travel to his hometown in order to communicate the news of the death to his mother. The camera begins to perform a kaleidoscopic encirclement of a rooftop that looks down upon the city below, and a voice begins to float, overlaid onto the image. “How many violent deaths…”, it asks, “…this is how spirits break, this is how skulls are split open.” And even as one of Hari’s friends—presumably the owner of the voice—aligns himself with the axis of the camera and begins to chart a bipedal trajectory in tandem with it, the contemplation resumes, “….what do we get in return,” before the scene concludes with a collapse into Socratic admission: “…I don’t know, I don’t know,” it mutters. The anxious intensity that lies at the beginning of the scene is reduced to a mere mumble by its end—a gross, existential fluctuation that will permeate the entire film.

II.

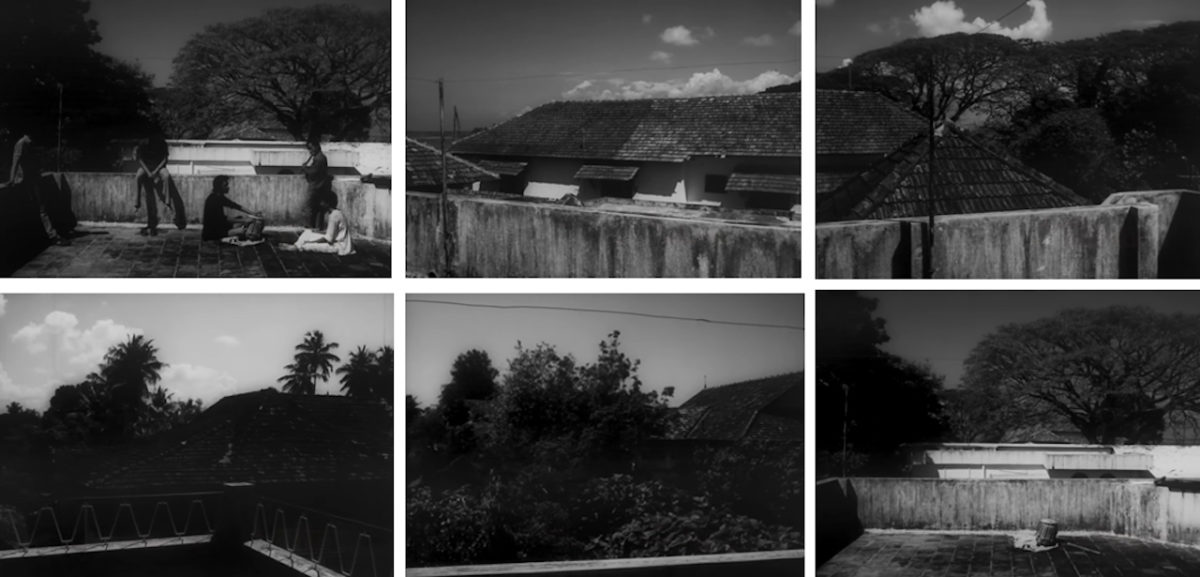

In another scene, which takes place much later in the film, but also set atop a roof, Hari is seen playing the tabla alongside a group of his fellow classical musicians, each of whom perform their own respective instruments. The film is suddenly possessed by the rhythm of the song and the camera, enraptured, begins to travel along a circular path upon the plane of the roof—the music continues to play as the camera continues to travel; a splendid synthesis of cinema’s material, until suddenly, the percussion reaches a crescendo and the performance comes to an abrupt halt. Within a beat or two, the camera completes its journey and arrives back at the point of its origin: the image is now empty, the musicians have all left, they have taken their instruments with them, and a solitary tabla remains. Abraham affects through this move, as in the previous circumscription, a glorious decay—in that case, of spiritual tension, of a desire for clarity, of blasé rhetoric, and in this, even more radically, of the song first, and then, of the image itself (and to think, composition is central to both of these; but by the end, both decompose).

Amma Ariyan remains enmeshed within similar cycles of becoming and then unbecoming—it is at its heart a road-movie which recognizes travel as an opportunity for the accumulation of a tableau of consciousnesses. (A trait it shares with another seminal Indian film, where the filmmaker takes a train journey to document the inevitable crumbling of a romance: India at 20 (1967), by S.N.S. Sastry.) As the characters in the film—a strident caravan of the young who have misgivings—move across the landscape of Kerala and reach its various major centres, they become the conduits through which mentions of the particular city’s historical trysts with violence or oppression enter the film’s own narrative. This causes the film to function out of a strange fugue: the bodies of the characters are all here and visible, but their minds are always displaced, fugitive from their lived reality. In this, Abraham uses Amma Ariyan to posit a formidable definition of politics: an exercise that allows for a continuous and perpetual formation of new meanings.

The young men who haunt the film are typified in the film through the character of Purushan (a name that interestingly means, in essence, ‘person’, or ‘self’, or ‘consciousness’ itself; he is everybeing), the individual who the film begins with but whose presence is subsumed gradually within the larger group. The opening of the film frames his departure from home, where he prepares to leave his mother (the titular ‘Amma’) behind, in order to fill an employment opportunity in Delhi, the national capital. His mother extols him to keep her informed of the progress of his journey by writing letters to her (the title of the film translates roughly to, ‘Report to Mother’—even though it is encouraged in certain quarters that the original be used instead of the translation, owing to its larger, semantic connotations).

III.

Purushan’s conflict seeps into the film rather early: as soon as he steps out of his home, his individual crisis begins to inhabit the film. As he walks the forest path that leads out of his village, his interior complication leaks in as a voiceover. At the outset itself, it laments, “…why must I go? I don’t want to go. In this village, dry and scorched, I seem to find myself…”, but even so, he continues to tread further. Later on, he takes a bus, transfers into another private vehicle, continues onwards on his journey; until suddenly, a rupture: the police have blocked the road and need the vehicle to transport a freshly discovered dead body. As Purushan disembarks from the jeep and sets sight for the first time upon the cadaver, a churning seems to transpire within him. He decides to not leave for Delhi, and instead devote himself, at first, to the establishment of the identity of the deceased, and then, to the communication of his death to his mother. The rest of the film assumes an epistolary format: Purushan continues to report—a collection of intimations, reflections, confessions—to his mother, who waits, as all mothers in the film must, at home.

In Amma Ariyan, however, the mother-figure comes to constitute a strange anomaly: Abraham revises the icon imposed on her in mainstream cinema, where the ‘mother’ came to represent a fixed, immutable idea of India itself, and instead allows her to emerge as an abstract, developing subconscious, which resides within the characters—not autonomous of them, but resident within their being.

A sequence occurs and recurs through the film: whenever the bandwagon of men arrives at the door of a prospective recruit to inform him of Hari’s death, he inevitably goes to his respective mother to inform her of the tragedy, and asks for her permission to leave for Hari’s hometown. The film assumes in this manner a cyclical posture—a ritualistic séance through which Hari is resurrected as a myth; bit by bit, organ by organ, an impression of him is sutured together, in order to composite, finally, a seeming whole, but one which one cannot be entirely certain of (when his mother is finally informed of his death, she remarks, “…even I did not know who he was, or what he truly wanted.”—nor do we).

IV.

The figure of Hari comes to occupy a near-archetypical position within Abraham’s oeuvre; and emerges eventually as the most radical enactment of the being that the filmmaker spent his fifteen-year-long career attempting to manufacture: an individual who will resist, but who will eventually fall to the immense oppression of the institution that hovers around him, above him.

Abraham’s Donkey in a Brahmin Village (1977)Also available on YouTube, courtesy of Potato Eaters Collective. witnesses a series of expulsions: Professor Narayanaswamy is ridiculed for his decision to adopt a donkey as a pet, the donkey itself is punished for its desecration of the village, and Uma, the professor’s mute and dumb helper, loses her mental balance when she witnesses this horror. Similarly, the protagonist of Cruelties of Cheriyachan (1979)And yet again Potato Eaters Collective offers the restored version on their YouTube channel. undergoes a spiritual unbecoming when he sees the police enact barbaric violence upon a group of poor peasants. Much like them, Hari exists not as a person, but a myth, composed through diverse, anecdotal accounts of him—a status accorded, ironically enough, to Abraham himself, who is reanimated in the annals of Indian film history through the legends that surround him.

The film presents no definite account of him, but merely the contours to his spectre—we form, at best, a notion of who he may have been. This means that the news of his death elicits a diversity of responses from the litany of individuals who receive it: some react with shock, others with indifference, while the remaining with an outright dismissal (“he was half-mad”). Another one, his erstwhile roommate, remarks, “he was a musician, but he did not sing political songs…” Throughout the film, Abraham affects a deliberate obfuscation: Hari is not one thing or another, but exists as a fossil of imagined truths; a colony of ciphers.

In this, Amma Ariyan demonstrates a marked shift in Abraham’s own preferences as a filmmaker. While the film shares its disdain for the effects of institutional tyranny on the spirit of an individual with both Donkey in a Brahmin Village and Cruelties of Cheriyachan, its articulation of this sentiment is filtered through an entirely novel register. With Donkey…, Abraham engages an observational, semi-realistic aesthetic that activates the village of its title and the chief events that transpire in it with the distant, detached draughtsmanship of a company painter—in fact, it is only with its final sequence, where cosmic forces set the village asunder, that the film begins to acquire a fulminous fervour. In Cruelties… he transitions fully to this expressionism, when he recruits the assertive geometry that surrounds the character—here, one is reminded of the films of Hideo Gosha and Nagisa Oshima, directors who were artistic predecessors to Abraham—to relate to the audience his tremendous paranoia: a greater depiction of mental illness may not exist in Indian film. Filled with the guilt inherited from his witness of drastic barbarism, the titular protagonist spends his time merging himself with the shadows: he hides under the bed, climbs into the loft, atop a tree, in the shed, and in one sequence, bears the cross (literally). It is with Amma Ariyan, however, that Abraham transcends mere commentary and instead carves as his locus the muckiness that inhabits the interior selves of his characters.

Even as Purushan’s body—as the bodies of the other members of his convoy—surges forward in its chosen exodus, he cannot be entirely present: he is here, but also, elsewhere. At various points in the film, his character stares out of the window of the moving vehicle he and his friends are in, and launches into singular flights of fancy: he imagines a union between the mother he has abandoned, and the lover he has left behind. He thinks of the two women, dressed in pristine, traditional saris, as they stroll around the ancestral house, and commit themselves to the performance of a set of most mundane, daily activities (they pray, they fold clothes, they sit, they amble, they stare). His being is rendered—as are the various other aspects of the film—through a peculiar adulteration: he participates in organized politics and seems to believe in its radical ambitions, and yet, also longs for the conventional comforts of an ordinary, folk existence. Abraham establishes—much like Arun Joshi does in his books, and who remains Abraham’s closest spiritual cousin—the impossibility of absolutism within a country where life is marked by a set of shifting, slippery realities. This must yield, therefore, a life of continuous navigation, movement and confusion.

This ensures that the ‘political’ in the film manifests too through mere cosmetics: a litany of text looms over the film, often in the form of direct and visible quotations: as passages read from a book, a speech delivered by a union-leader in the distance, or as voiceover; devoid of passion, a string of words, voluminous but rhetorical. The lack of sentiment allows for Abraham to erect a universe where his characters operate under the influence of a diverse set of streams that exist not within a vertical hierarchy, but parallel to each other, besides each other, as a series of expressions of ‘and, this too’, as opposed to ‘or this’. (Here, Godard’s use of the book-object as a cosmetic object, or in general, words as decoration in La Chinoise (1967) comes to mind; as also the universes of the films of Matias Piñeiro, where characters are subjects under regimes of text.)

Abraham’s construction of this Hegelian-framework of nuances extends, even more significantly, to his method of employment of the image in relation to the text that continues to ambush it. In a scene where a young man visits another’s house to inform him of Hari’s death, he settles down with a printed catalogue of images of atrocities from around the world. The leftovers from a conversation about astrology, superstition and ritual from the neighbouring room filter into this, and are laid as contrapuntal narration over the set of depictions of the grotesque consequences of an uber-scientific, modern world.

Such similar gestures allow Abraham to set up a series of paradoxical constructions that exist through the film, a set of eternal scrambles: between faith and science, between the heroic and the ordinary, between subscription and disavowal, and between—most significantly for him—an individual’s cultural and essential selves. He extends this to the material construction of the film—which builds often on the rhetorical dialecticism of Sukhdev and S.N.S. Sastry—with sequences where this confusion becomes most pungent: as Hari and his fellow musicians perform a tranquil tune in a flashback set upon a beach, the director suddenly cuts to the image of Hari’s dead body stored inside of a drawer inside the morgue—a device employed to heighten the tragedy of the loss of his youth, the loss of any youth.

A radical despair therefore manifests in his cinema—the strongest expression of which is the permanent ‘lostness’ that is expressed in Amma Ariyan—but this is not a despair born out of an inability to believe in anything at all, but from an aggressive acceptance of doubt itself, and therefore, from a belief in the very act of non-believing. When Abraham, a staunch atheist, was invited to Rome for a presentation of his film at a festival, he wrote from there to Adoor Gopalakrishnan, a compatriot from the old days at the film institute in Pune: “I am not proud of being a Christian, but the architecture here may convert me.”

Amma Ariyan’s jagged form itself, which allows it to exist as a portmanteau of different filmic styles—its editor, Bina Paul, describes it as an odd assortment, or as fiction with the anthropological impulses of documentary—seems like a result of Abraham’s own disillusionment with the then prevalent mode of industrial filmmaking. The films of the so-called ‘parallel cinema’ could, for instance, appear sophisticated and elegant, even if they were about ugly realities or truths. Amma Ariyan marks a conscious disregarding of this model and an embracement, instead, of poverty in cinema. It exists as such as the most potent example of the intention put forth by Odessa Collective, a co-operative which posited an alternative model of film production, which, in essence, would use resources gathered from the people to produce films, and who would also then become its first and primary audience.

As such, Amma Ariyan remains, much like its protagonists, in a state of perpetual flux—a film that is being made in the present tense; a landfill of gathered stimuli, rather than a monument born out of design. This present-continuous quality allows Abraham to engineer, on-the-go, several of its chief accomplishments: from the scenes that depict workers arranged in serpentine queues to collect their rations, to one which sees Purushan sit atop the hill that is the location of the suicide and begin to conspire a redemption for the dead, and eventually, one suspects, the ending, where the film itself becomes a projection on the screen, in a gesture that constitutes one, final mutation.

V.

Regional cinema production in India, through its relay of hyperlocal contexts and homegrown narratives, sought an immediate decentralization of the national film canon, forged as the latter was in the image of the Nehruvian vision of India: a unitary, homogeneous state that must imbibe centrally mandated virtues of scientific temper, industrialisation, a definite individualism and a ‘modern’ outlook—qualities presumed necessary in the evolution of a freshly independent country. Curator and Art Critic Premjish Achari told the author, “…in my film studies course at a major central university, I realized that the movies from languages other than Hindi, the so-called vernacular, remained invisible from within the curriculum. I am not making a case for inclusivity or pluralism of material choices here. The canon is built on the comfort of a pre-given timeline starting from Independence onwards to liberalisation and then advancing to the arrival of global capitalism. There are plenty of examples from Indian cinema to dispel this narrative or allowing us to further complicate the picture.” Various institutions have, of course, pursued the cause of a canon-formation in India, from archives, to defunct print magazines, to digital museums, to websites, but it remains an exercise that is fraught with complication: how does one consolidate that which is essentially a manifold? In this, regional cinema is defined by examples of films that assert the essentially federal and dare one say, fragmentary nature of the Indian republic—to reconstitute them into a single whole, which while possible, will still resemble a distortion at best; a Frankenstein with odd stitching.

Even so, and even within the most pertinent examples of films from the different regions in the country, there remains a distinct tension: a negotiation of the question of belonging itself (and to whom?). As a result, the films’ declaration of their disenfranchisement becomes, as a corollary, an acknowledgment of the franchise itself. This is to say, even as they portray a disillusionment with the central tenets of the Constitution, they still choose to exist within the paradigm of the same discussion. On the other hand, Abraham’s films abandon this cause entirely. Instead, he continues to lay out the blueprint for a utopia where an individual may finally be extricated from any institutional affiliation (when the titular protagonist dreams a nightmare in Cruelties of Cheriyachan, the figure of the landowner floats over him, followed as if on a conveyor belt, by the priest). As such—and similar to the films of Shinsuke Ogawa, to whose curious conflation of documentary and fiction Amma Ariyan owes its central propulsion—the ‘nation’ emerges, as in the summary of Ernst Renan, a ‘daily plebiscite’, a discussion through which the characters can choose to navigate this question every living second. In this, therefore, Abraham aims to install in his films a true modernity, one which prioritises, above all, a postulation that is the motor of all new wisdom: it reads, “I don’t know.”