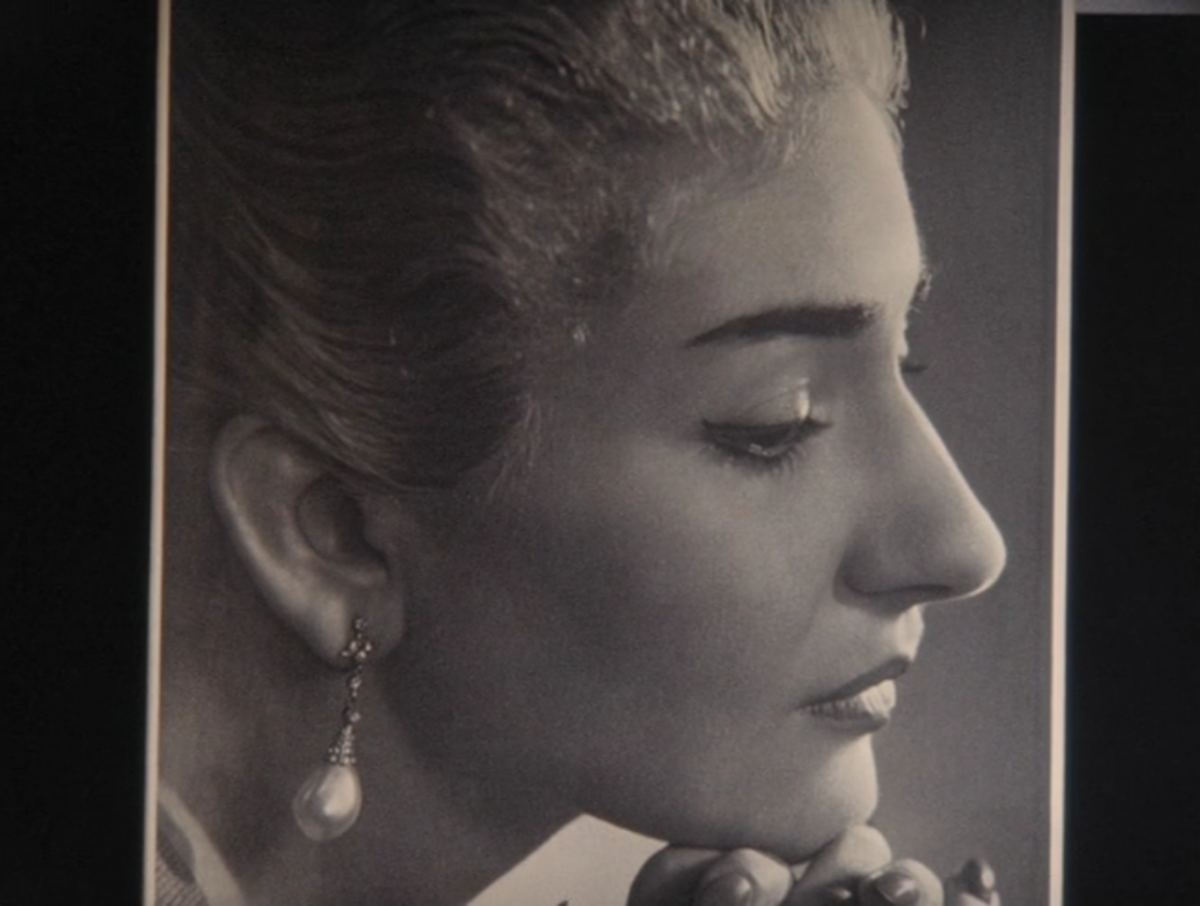

Grand opera diva Maria Callas’ position in the history of cinema is a collection of strange paradoxes. She worked with Italian directors Luchino Visconti and Pier Paolo Pasolini, but is nowhere else so prominently present as in the films of the German filmmaker Werner Schroeter, placing her at the heart of the New German Cinema of the late sixties and the seventies. However, Schroeter and Callas never actually worked together. Their relationship is based on a one-sided admiration and idolatry, with Schroeter adding Callas’ voice and photographs to just about everything he brought forth, as if looking for her approval. They briefly knew each other, having met for the first time around 1974, only three years before Maria Callas passed away, but long enough for Schroeter to find out she had a “melancholy humor” similar to his own. Schroeter wanted to make a film with her, but never got the chance to. Nevertheless, this did not stop him from incorporating her into his films, and the various ways in which he does so allow a rethinking of what it means for a performer to be present, even if they are not present at all.

Callas im Kino

Even though she died much too young, Maria Callas, playing leading roles in major operas before WWII, had already changed the face of the artform at a very young age. Although her technique was outstanding, her musicality unquestioned, she favored dramatic expressiveness and tragicism in her voice and gestures over the habitually expected brilliant (as in crystal clear) vocal performance, shocking the people. You either loved or hated her. It almost made her a (tender) rock star. In his memoriam to her, Schroeter mentioned her next to Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, in addition to the oft-made comparison with the 19th century vocalist Maria Malibran, who was just as popular a diva—and a force to be reckoned with—in her own time. To Visconti, Maria Callas was Maria Malibran and it was because of Callas that he staged La sonnambula in the Italian opera, as an ode to Malibran—which he did immediately after shooting Senso (1954). Visconti had often stated he turned to opera out of love and adoration for Callas. They continued to work on a handful of opera productions together, such as Spontini’s La vestale in 1954 and Verdi’s La traviata in 1955, but they never collaborated on a film. According to Pierpaolo Polzonetti, the Italian critic Teodoro Celli “accused Visconti of treating Verdi’s music as a film score of one of his movies and of contaminating Verdi with neo-realistic aesthetics.”

All three filmmakers, Visconti, Pasolini and Schroeter, when asked “Why Callas?”, stressed how she naturally dominated every room she was ever in. Being a very tall woman, for Visconti she was nothing less than a Greek goddess; Schroeter said she could only be compared to those mythical figures she brought to life on stage; for Pasolini, she had an unquestionable tragic aura, being the only actress who could express “spiritual catastrophe” without uttering a word. For Schroeter, she eventually meant many things and adopted many forms and shapes, which mutated throughout his oeuvre. She was the cause of his tormented love, she was his muse, she was the reason he studied Italian, the reason he fell in love with opera. Perhaps most importantly, she was the absent muse to complement that conversely ever-present muse Magdalena Montezuma with whom Schroeter worked together on practically every one of his theater and film productions until Montezuma’s death in 1984.

Both women had a statuesque figure with highly distinctive features: big almond-shaped eyes and large noses. Combined with ever gracious and sensual movements, they appeared to be living sculptures, moving their limbs as if they were heavy as marble. Montezuma did the make-up and costumes for most of Schroeter’s films and often painted herself completely white, accentuating her own angular face. Callas never hesitated pulling an ugly visage whenever a role requested intensive emotional buy-ins. At the opera she was often booed because the audience felt she was too much of an actress, too little a singer.

Intrigued by the grotesque, the larger than life, the mythical, Montezuma and Callas embodied Schroeter’s variegated fascinations and allowed the director to tell stories through expressive physical appearances, through small gestures, through fragmented imagery, through music. His cinema consists of a continuous layering of things he found, read, collected, recorded. As diffused as all kinds of things came into his life (art, poetry, love), willfully or contingently, it entered his work in a similarly ethereal sense. Mismatching time and place, body and voice, allowing things to happen unexpectedly, mixing up stories and styles, Schroeter assembled his films with the leftovers of life and love, hardly containable in narrative structures and coherent plot lines.

Maria Callas always stressed the fact that she was an actress—opera is more than music. In a similar gesture, Schroeter claimed he hated his work being called “operatic,” because it is so often used in a pejorative sense. Both artists imbued their work with a sense of vitalist tragedy, simultaneously living and dying for it; a way of working, through knowing what you’re after, not confusing art with life, but self-consciously erasing the difference between the two, at a (large) cost. Callas often rephrased she wasn’t an optimist. Schroeter calls her to the scene in the most disheartened, unmistakably sad moments. In Goldflocken (1976), one of Schroeter’s last and relatively pure collages, Magdalena Montezuma is lip-syncing to Conchita Supervía in the opening minute and is heard truly singing the Cuban national anthem a bit later. In a third close-up, in a chapter called ‘Death’, she is once again engaging with the soundtrack—Maria Callas singing the overture of Verdi’s La forza del destino—but this time Montezuma doesn’t sing nor imitate. Behind bars, she listens. Her eyes, her brow, her chin is reacting, but her lips hardly move. They merely tremble to the weight of Leonora’s words opening the opera, ready to give up her family for love. The possibility of cinema to capture these miniature gestures is what attracted Callas to the medium. Close-ups allow for gestures to be small. Someone’s skin, in all its psychological intimacy, can fill large screens entirely and wordlessly.

And wordlessly she appears on the silver screen. Although she was offered many roles, Callas deliberately chose Medea (Pasolini, 1969) as her debut (and unfortunately also her closing act) in cinema, convinced it was important to make the right choice. Pasolini greatly displays her expressionist features but silences her, although that was also Callas’ decision. Callas pushed Pasolini to drop the music, to free Medea from the extraneous. Her pain and anger do not require large and loud notes, they are expressed through her fiery eyes. Apart from not singing in her role as Medea, Callas’ voice is also dubbed in Italian. For the first time, she is only moving in visuals, molded by the hands of Pasolini. Choosing and being Medea most likely added to the living myth that Callas was. Schroeter however felt that Callas’ “special dramatic character” could only be incited/invoked on stage, apparently insisting on the liveness of the medium. It reiterates the question of how to unite Callas’ absolute absence in his films with his desire to have her present at all times.

Une voix plein d’images (8mm)

Schroeter’s fascination for Callas began when he was about 13 years old. It will take another 12 years before he meets the woman whom he refers to as the mother of his art or, vicariously megalomaniacal, a messenger from the Gods. Callas meant the beginning of his film career: he first experimented by ‘animating’ magazine snippets of the performer, recording her off the radio and transferring these fragments onto film. He collected these snippets and advertisements in an album already as a young kid and refers to them plainly as memorabilia.

What he did in these first experiments where Callas is inspiration, content, form, title, method—and all else that a film is—was create movement with the objects he found that had her face or voice on them (stage sets, records and their sleeves, newspaper images, opera house advertisements and so forth). He framed, alternated and repeated pictures, made cut-outs, split screens, passe-partouts. He brought Callas to life, animated her, albeit still in an austere manner. The movements are subtle, elegant but also stiff, and it is Callas’ absence that prevails in the overly focused Maria Callas Portrait (1968) for which he made 2 preliminary studies titled Callas Walking Lucia and Callas Text with Double Exposure. There is another Callas film from the same year, titled Maria Callas Sings, 1957 which consists of a ten-minute recitative and aria from Verdi’s Ernani.

Nevertheless, Schroeter was already researching how he could (re)present the diva in these short films, which never lasted more than 15 minutes. He doubled her voice and had her singing duets with herself. The montage is fast-paced and adds movement to still set pictures. Elsewhere, the director’s own hands come into view, bringing both absentees together. In his memoir Days of Twilight, Nights of Frenzy (2011), Schroeter also warm-heartedly mentions a short film where Carla Aulaulu is playbacking to a track of Callas, a film that was never released. Instead there is a similar one, titled simply Carla where Aulaulu is playbacking to a German schlagerlied—often the counterpart to the long, intense hauls of opera in Schroeter’s films. Apart from these works that carry Callas’ name, the mezzo soprano can be heard in practically every other film he made in 1968: Mona Lisa; La morta d’Isotta; Johannas Traum, and so on. Callas was Schroeter’s guide in his earliest experiments with film, a kind of known and trusted woman—his spiritual mother—that offered him the confidence to go on and experiment in his further career, to create with her imagery, rather than using it. In his feature films, Callas is no longer a complete, unquestioned element, she is no longer the title kid, Schroeter no longer paints her portrait.

Cutting up Callas (16mm)

Only a year after his first experiments, in the full-length opera collage Eika Katappa (1969), Schroeter doesn’t hesitate to cut up Callas or even to silence her entirely. In his autobiography he wrote that he tried to sabotage normal narrative structures by carefully puzzling the soundtrack together—which he meant “affectionately”:

At the end of the film I had a picture of Callas, accompanied not by her own voice but by that of Celestina Boninsegna, a fine Italian spinto soprano. I was playing with the myth of Callas, linking her image to the sound of another voice. It was up to the viewers to gauge where the ‘truth’ of the performers’ identity lay.

He lets us in on this one occasion, but the image he speaks of returns at least four times in the last five minutes of the film and by extent the entire film is full of pictures of Callas, matched with her own or someone else’s voice. (These are all inside jokes for people who are well-versed in opera.) Apart from moving cut-out images of her before a camera, Schroeter adds a new way of turning Callas into one of his performers: the pictures of her serve as title cards, or still-image-breaks in which Schroeter switches music, moving from the sway-along of ‘An der schönen Blauen Donau’ or the Schlager-classic ‘Spiel Noch Einmal Für Mich, Habanero’ to an aria sung by the soloists Callas, Boninsegna, Dame Joan Sutherland, Maria Cebotari, amongst others, leaving in a second or two of silence to change the record.

In a singularly extraordinary instance, hardly noticeable but of great delight when discovered, Schroeter fools us all. The director spent entire nights cutting together the music for Eika Katappa. Halfway through the film, ‘Tu che invoco’ is set in, and what you hear is the Scala Orchestra Del Teatro, led by Serafin, who shaped Callas’ vocal performance, in a recording that is supposed to have the actress as the leading voice. Yet, right before singing the first note, Schroeter cuts the recording and adds instead a much older tape, of a lesser material quality, bearing the voice of Rosa Ponselle, who obnoxiously (yet beautifully) rolls her ‘r’s for seconds to last and who is most definitely not Maria Callas. When you know it, the cut in the soundtrack is very audible. Switching records without cutting the composition, moving obviously towards a worse iteration of the song, is no coincidence. Schroeter kept Callas to himself, and the truth of the performer’s identity becomes an infinite (and unfair) game. Through this “radical split between body and voice” such as Gertrud Koch describes it, these sequences overcome the status of memorabilia, of objects of idolatry or portrait pieces. It is no longer an ode to an absent Maria, as she is most certainly present. Or in a Hegelian sense, her absence provides space for new things to come into being. Most often, Montezuma enters this open space, Callas, Malibran, perhaps Ponselle with her, preventing the gesture from falling back into nothingness.

The love-triangle of Callas, Montezuma and Schroeter—in between whom there never actually was a romantic love—was adopted by R. W. Fassbinder in Warnung vor einer heiligen Nutte (Beware of a Holy Whore) in 1971. Fassbinder supposedly asked Schroeter if he could copy a scene from Eika Katappa (1969) depicting a young man sitting on a boat, accompanied by a song from Austrian composer Hugo Wolf. [Pictured below, on the left. – ed.] Fassbinder replaced the young gypsy with Montezuma wearing a blond wig and added a track of Callas singing Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, turning the scene into a complete, rather vapid ode to Schroeter and his then-still humble cinematic universe. In Beware of a Holy Whore, Montezuma plays the heartbroken assistant of the director. [Pictured below, in the middle. – ed.] In reality, the voice of Irm Hermann—at that point the ex-girlfriend of Fassbinder—overlays Montezuma’s performance in the film entirely. Apart from making Montezuma more or less look like Hermann, the wig also seems to refer back to Carla Aulaulu’s short blonde coupe, as does the make-up. In 1970, in between Eika Katappa and Fassbinder’s Holy Whore, Schroeter presented Der Bomberpilot, in which Aulaulu is seen sitting in a boat, wearing a large hat, divalike. [Pictured below, on the right. – ed.] A regular in Schroeter’s early films, Aulaulu becomes part of Fassbinder’s clear-cut tribute to the director.

“Long-keeping sausage” or doing away with sensuality

In Eika Katappa Schroeter has great fun—he admits playing with “the myth of Callas”—juxtaposing Callas’ voice with Magdalena Montezuma’s intentionally off and lazy lip-syncing. Magdalena Montezuma and Maria Callas are two irreplaceable girders in the entirety of Schroeter’s imagination and after the two were briefly absent in his neorealist projects Palermo oder Wolfsburg (1980) or Nel regno di Napoli ( The Kingdom of Naples) (1978), the director reintroduced them into his later work. More than twenty years later, in Deux (2002), Isabelle Huppert plays a twin called Maria and Magdalena, embodying the Callas-Montezuma-duo. In the same film, we hear Callas sing ‘O madre mia’, an excerpt from Ponchielli’s La Gioconda, which tells a story that revolves around three women—no unusual premise for Schroeter, think of the three ex-Nazi-entertainers on the search for a new job in Der Bomberpilot or the 1973 American melodrama Willow Springs where love (literally) kills the friendship between three young women. Contrary to what the title suggests, in Deux many more women are called to the stage, but at the core again there is the trio of the twin and their mother, making the soundtrack fit the general plot of the film perfectly.

In these later works, Callas is content and complement, an all-around less experimental approach. But to call her voice into existence after her death—Schroeter wrote, “to call the sensuality of her voice into being again”—as if she hadn’t died, made him feel uncomfortable:

At heart, I didn’t want that divine voice to be preserved on disks for infinite repetition, like a long-keeping sausage, as I once put it in conversation with my friend Daniel Schmid.

The way in which Callas is contained and subsequently featured in Deux is very different from the more experimental phase that precedes it. In the earlier works, sensuality lies in a lasting tension, in the subtle tear at the edges of the magazine snippets, in the slight crack in Callas’ voice, in Montezuma’s lazy lip-syncing or in the slowed down, beautifully controlled movements which take the godlike woman from her pedestal, a place Callas had an ambiguous relationship with anyway. Sensuality is an essentially human concern, one that is central to tragic longing, to operatic theater, to a gloomy form of aestheticism.

If we must divide Callas’ presence into discrete parts, Deux represents the homecoming of the spiritual mother, opening the jar with the long-keeping sausage (not a very sensual image indeed), allowing it to be sandwiched between/scattered over content and form, to be consumed entirely, to be used up. Callas is indirectly part of said story and she is integral to the way it is told. She is the contouring of her own shadow, she is both present and absent.

Ultimately, Schroeter is in full control of Callas’ presence in his work. She never appears alive or moving. She is being moved (or pictures of her are moved), lights are shone over the pictures to create movement, her voice is ‘summoned’ or cut off. On the other hand, Callas also slips out of the director’s hands, who can only work with what she has already done, what she has already been, with Callas the internationally renowned diva. Callas can never truly act, never be anyone else in his films, she cannot be molded or transformed the way she could be by Pasolini. However, to keep all the pieces of the puzzle from falling too neatly into place: in her many works on stage in large operas, Callas did embody fictional and mythical characters (Tosca, Medea, Carmen) over and over again. So entering Schroeter’s films, she already is a collage—of herself, of her stage persona, of the many versions/portrayals of those fictional figures that came before her. Add to this Schroeter’s film concept, the sounds over Callas’ image, the images over her voice, and the pairing of Schroeter and Callas appears not as a sovereign artist’s one-sided manipulation of innate material, but rather as the interplay between director and performer.