The ‘artist documentary’ is by no means a new genre. In fact, documentary films on artworks and artists have existed since the emergence of cinema, rising in popularity throughout the twentieth century alongside its historical-fiction complement that employs actors, the artist ‘biopic.’ Nonetheless, artist documentaries produced within recent years continue to grow in popularity and have taken on figures from high art to popular culture, from artists Eva Hesse (Eva Hesse, 2016) and Robert Mapplethorpe (Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, 2016), author James Baldwin (I Am Not Your Negro, 2017), to the late singer Amy Winehouse (Amy, 2015). Despite their marked differences, these films (and artist documentaries more broadly) deploy footage of artistic lives defined by exceptional creativity—often alongside eccentric personalities, outspoken political views, and personal scandals. Beuys (2017), Andres Veiel’s documentary on the prolific German artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), is the newest addition to the increasingly visible genre. Yet whereas some artist documentaries, at their best, formulate new modes of historical narration and can critically reappraise an artist’s oeuvre and life, Beuys obfuscates Joseph Beuys amidst the controversies that his name and image have come to mythologize.

Beuys is unique in its stylized visual scripting, where original photographs and filmed footage of Joseph Beuys are edited in succession, privileged over chronology, interviews, interpretive commentary, and present-day imagery. As The Guardian reports, the original Beuys was planned to be only 30% archival footage; its final version is closer to 95%. Beyond being an impetus for creating a documentary, the sheer abundance of the archival footage of Joseph Beuys is simultaneously the most prized and undermining constituent of Beuys.

The most evocative affordance of what ultimately reads as an excess of archival material is the possibility of glimpsing Joseph Beuys’ process across artistic, pedagogical, and political endeavors. Most renowned for his maxim “everyone is an artist,” Joseph Beuys sought an “expanded concept of art” that emerged in non-exclusive social forms. In addition to the everyday and organic materials to which Beuys was inclined (most notably fat and felt), his art practice and identity transgressed disciplinary categories and included didactic, performative, and shamanic activities of extended duration. However, the film’s most intriguing archival footage of Beuys is not of his artworks, but rather of his work as a professor and aspiring politician.

Beuys taught as a professor of sculpture at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1961 until his dismissal in 1972. The archival footage in Beuys provides a fascinating depiction of Beuys’ animated lecturing style as well as the mass protests that ensued among his expulsion from the academy. Beuys rebuked the academy’s admissions process, inviting all rejected applicants to attend his seminar—leading to the academy’s rescinding of his teaching position and the gripping footage of the students’ and art world’s outrage over their decision. Moreover, the film’s recordings of Beuys’ involvement in the founding of the German Green Party and his sense of political disappointment at failing to become an elected official reveal the artist’s depth and manifold aspirations irreducible to singular artworks or the artist’s performative persona. The film’s illustration of Beuys’ inclusiveness and activism within the academy and the political realm provide compelling counter-narratives against his reputation for idealism, absurdity, and self-mythologization.

Yet such redeeming elements of the archival footage, which constitutes Beuys nearly in its entirety, are overwhelmed by the film’s insufficient quantity of interpretive commentary regarding Beuys’ artworks and biography. Neither clarifying, critiquing, nor preserving complexities and contradictions, the film’s vague narrative and lackluster sequencing of the archival materials suspend Beuys and his artworks amidst the myths and omissions from which their controversies stem. For instance, Beuys fails to meaningfully revisit the artist’s voluntary participation in Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe during WWII. What could have been an opportunity for a revisionary interpretation of the motifs of complicity, guilt, and trauma evident throughout Beuys’ oeuvre (such as in his recently uncovered, yet unfortunately unmentioned, 1957 proposal for a memorial at Auschwitz) is lost amidst unproductive archival images that romanticize artistic clichés of destruction and rebirth.

The film instead adheres to Beuys’ identity-concealing self-promotional legends. A full interview is shown, in which Beuys recounts his artistic ‘origin myth.’ Supposedly crashing his plane in Crimea during WWII, Beuys maintained that he was rescued by Crimean Tartars who healed his injured body by wrapping it in fat and felt, thus mythologizing his frequent use of fat and felt throughout his sculptures. That it is widely known that this event never happened and was fabricated by Beuys, and that Beuys presents the artist’s recounting of the story without any dispute or critical commentary to frame the interview ultimately does a disservice both to Beuys and to the viewers attempting to understand his controversies, provocations, and strategic fabulation. Leaving the archive to do the work of narrators, editors, critics, and historians thus mystifies Joseph Beuys amidst the noise of his own antics.

Ultimately, that Beuys is unable to ask the right questions results in an incomplete representation of his outstanding artistic oeuvre. Perhaps the most illuminating aspect of the artist documentary genre is its ability to present and interpret an artist’s entire output within the short duration of a film (such as in Eva Hesse and Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures), thus presenting chronological breadth paralleled only in museum retrospectives. However, the vast quantity of archival footage in Beuys seems to operate in an inverse relation to the number of artworks discussed. While striking footage of several canonical performances is included and critically contextualized, such as his monumental tree-planting “social sculpture” 7000 Eichen / 7000 Oaks (1982-87), too many works are regrettably omitted, including Unschlitt / Tallow, the spectacular sculpture comprised of 20 tons of fat cast under a pedestrian ramp at the 1997 Skulptur Projekte Münster. Another inexcusable erasure of context occurs in the presentation of Beuys’ 1976 Venice Bienniale installation Straßenbahnhaltestelle / Tram Stop. While many archival photographs of the installation are presented in sequence, no narrator (art historian or otherwise) describes the artwork, especially its entanglement of visible associations: the tram stop in Beuys’ hometown of Kleve, its French Revolution iconography, the monumental sculpture of the Third Reich, and the train transports of the Holocaust. Archival excess met with absent commentary in Beuys thus neutralizes the complexity of Beuys’ artworks amidst the atemporality of what visually resembles a Google Image search.

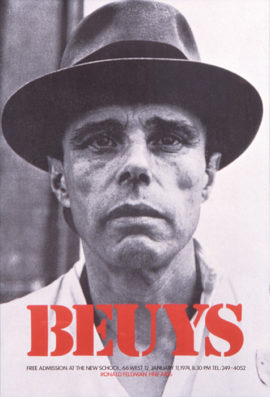

At various points in Beuys, the camera pans over contact sheets of innumerable photographs of Joseph Beuys. Singular photographs, most often frontal black and white portraits of the artist, emerge from the contact sheets and overtake the filmic frame. Beuys’ portrait is repeatedly presented, as if history, creativity, and identity can be read from his deep-set eyes, pronounced cheekbones, crooked nose, and signature felt top hat. The portrait fails to crystallize the explanatory work necessary for beginning to understand Beuys’ visceral artistic language and his intricate actions across art, education, and politics. Instead, it emphasizes the surface-level distractions of reputation and controversy that his image inherently calls to mind. The central question of Beuys is not of the artist himself but rather that of the archive, of whether a remaining abundance of photographs and film footage can meaningfully reconstruct an exceptional life and its multifaceted history. But rather than proceed with precision and commentary towards the possibility of new understandings and revised interpretations of the art and life of Joseph Beuys, the archival overload of Beuys instead leaves us viewers with fragments of myth.