A teenage boy looks into a bathroom mirror as it slowly fogs up with steam. The film cuts just as his reflection is arrested in the misty glass, and now the boy is outside standing on the banks of one of the various inlets that borders Helsinki, looking beyond the city and back at it. As a train approaches and crosses a tall concrete bridge spanning the water, the bridge collapses and the train violently nosedives into the murky black depths. Outside and inside are spliced and reversed as the film cuts again, and the boy is now trapped inside of the sinking train, gasping for breath as the carriage fills to its brim. Yet as water overtakes air, the boy does not drown but can seemingly breathe underwater, opening the train doors to glide alongside jellyfish, seaweed, and into the liquid abyss. Only as the dream withers away and reality gradually emerges on the precipice of waking up is the boy imprisoned again. Still underwater yet banging on an invisible glass plane as if trapped inside of an aquarium, the boy awakens.

Pirjo Honkasalo’s Concrete Night (Finland, 2013) begins with this haunting dream sequence, in which the teenage boy protagonist Simo (played by Johannes Brotherus) comes to terms with the end of his life and realizes a way to survive. A black-and-white adaptation of the Finnish novel Betoniyö (1981) by Pirkko Saisio, the director’s partner, Honkasalo’s Concrete Night takes Simo’s dream as the film’s organizing motif and progressively unravels its ambivalent meaning. Imbricated into the actual spaces of the film as it is mutually redefined by them, the dream and its visual hieroglyphs set into motion the film’s two sets of oppositions that overlap yet remain irreducible to one another—simultaneous entrapment and liberation in real and imagined spaces, and between fear and the possibility of hope. Upholding the generative conflict of these paradoxes, Concrete Night thematizes the fragility and freedom of life’s emplacements.

Concrete Night is set across a day and night in a social housing estate in Helsinki, where Simo lives with his erratic mother and his volatile older brother who is to be put into jail the day following the film’s time frame. Literal imprisonment is on the horizon for Simo’s belligerent brother, yet entrapment is already palpable in Simo’s daily life as the three are cramped into an undersized and sordid apartment within an expansive Brutalist housing block.

From Simo’s dream of constriction to its actualization in the architecture of his everyday life, the apartment forms the site of the film’s hopelessness, particularly through its symbolic alignment with the negativity of Simo’s mother and brother. Like the dream-image of being submerged underwater and trapped behind glass, Honkasalo’s filming of many scenes featuring the apartment’s windows functions to re-instantiate the former imagination of spatial confinement. In the various moments that Simo and his brother look out of the opened windows, their wobbly reflections double back onto themselves in the glass panes to underscore their estrangement from the outside world and the insurmountable distance from the graspable hope that it could potentially offer. Orthogonal grids of shadows from the window blinds are often cast onto Simo and his brother’s faces, further likening the apartment to the prison cell that awaits Simo’s brother. The foreboding present and future of incarceration in Concrete Night is written in the light of reflections and shadows.

Visible from his window, the apartment that directly opposes Simo’s in the adjacent housing block is contrarily emblematic of his dream of liberation within and beyond spatial enclosure as well as of the possibility of hope that haunts Simo’s existential detention. An unnamed presumably gay man, referred to by Simo derogatorily as “that poof”, inhabits the apartment. For Simo, the man is a source of simultaneous fascination, desire, and abjection, and later returns in the film as a figurative martyr of hope itself. When Simo gazes across at the man and into his apartment, the powerful Baroque voice and harpsichord cantata (Giovanni Battista Ferrandini’s Il pianto di Maria, 1739) that resounds from his living room immediately overtakes the film’s dissonant soundscape. Honkasalo thus draws an associative linkage between the man’s apartment and a church, further underlined in a scene where Simo wanders into an Orthodox cathedral and encounters the man singing in the church’s choir. The liberation into a spiritual space of the sublime that the man and his apartment together embody diametrically opposes the morose people and places of Simo’s world. Iconizing the queerness of hope, the man and his apartment function as Simo’s personal and spatial doppelgänger by dramatizing the tangibility of dreams set elsewhere from the imprisoning noise of quotidian disillusionment.

On a broader scale, the city of Helsinki functions as a character of the film’s irresolvable paradoxes—oneiric imprisonment and architectural liberation, and between lives inscribed with proximate fear and others lived through belief in a future of hope. One of the film’s symbolic sites is the fenced-off coast of an inlet, where Simo and his friend—both naked— run, swim, and climb on defunct industrial structures. On the one hand, this scene of homosocial pleasure and its spatial enchantment is figured through Helsinki’s Eden-like openness. However, this forbidden site, set on the industrial backside of Helsinki’s waters, foreshadows the return of Simo’s dream of simultaneous drowning and swimming into freedom, as the site is structured by imprisoning imaginaries that underscore the cruelty of optimism. Solely accessible through spatial trespass, escape is both dreamed and rendered impossible once the watery bank is reached. As Simo looks out beyond his entrapment in Helsinki towards the symbolic possibility of investing hope in an outside, what sits on the other side of the horizon is not elsewhere but in fact Helsinki reflecting back and closing in on Simo.

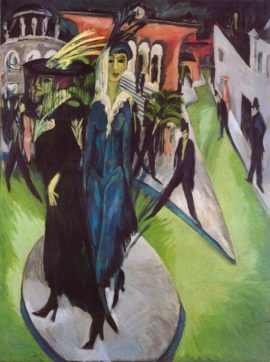

Urban scenes in central Helsinki constitute Concrete Night’s world of magic and reveal the interrelation of autonomy, pleasure, and danger. The dream-space of the train destined from its catastrophic sinking into a vision of freedom is actualized by the train transport throughout the film, which brings Simo from his claustrophobic housing estate into contact with the whimsical allure of urban encounters. The former image of homosocial purity, of swimming openly into the horizon, is directly contrasted with the sexual and spatial disorientation conveyed by the train station—his first point of entry into central Helsinki—where transvestites and hookers stare back at Simo to symbolize the monstrous otherness that opposes yet upholds his world. These figures of urban alterity conjoin Honkasalo’s modernist cityscape views, as Helsinki is filmed at sharp diagonals that disorient its structuring axes. Through these erotic images and expressionistic angles of a chiaroscuro cityscape, Honkasalo likens Helsinki to the experience of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Straßenszenen (“street scenes”) paintings cycle. Dreams structure urban spaces of bewilderment and recombination, oscillating irresolutely between entrapment within reality and a new way of seeing beyond it.

The imprisonment and liberation that Simo dreams into Helsinki’s lived spaces is magnetized in the architectonics of two conversations that lay out the film’s existential dualities. On a night out with Simo, the drunken older brother recounts his extraordinarily poetic apocalyptic vision in which humans have exhausted life on earth and scorpions will be the only species to survive the end of the world. As supposedly the only animal that can survive radioactive fallout, scorpions can also willfully kill themselves by stabbing their bodies with their tails. Drawing this premonition of science into a philosophy of life, the brother tells Simo, “The one thing in the world to be afraid of is hope. If you’re free of hope, you’re free of everything.” The hope of dreams constitutes the structure of fear that saturates the already-damned world; the evacuation of hope jettisons the bondage of everyday life to activate deeper freedoms.

Later on in the night, Simo winds up in the gay neighbor’s apartment. Attempting to seduce Simo, the man, in direct opposition to the brother’s former tale, narrates: “There are two things in this world: love and fear. In this world, there’s only one bad thing—and that’s fear.” For the man, fear negates the possibility of hope; rejecting fear actualizes the spaces of empathy and a belief in a structuring relation of love.

From its originary dream to its traversal of dreamed and lived spaces, Concrete Night builds its momentum up to these contrasting philosophical dialogues that fold back onto the spaces encountered in the film, retroactively situating their meaning within a spectrum of fear and hope. Impacted by the inverted philosophies and spaces of both his brother and the man, the young Simo nonetheless beats the man to death upon his continued seduction attempts. Running from the scene of his desacralizing crime to the Edenic space of the fenced-off coastline, Simo restages the image of his death, which came to him in the film’s opening dream. Beginning and end are dreamed into reversal as Simo removes his shirt, places it on the water’s surface to signify his drowning, and swims into an enclosure of freedom amidst the shadowy depths of the inlet’s abyss—a repetition of the opening dream’s sequence of liberation from the sinking train. The film ends with Il pianto di Maria replaying as Simo swims into the coexisting space between hope and fear—in life, in death, and in dreams. As Pirjo Honkasalo said of the film, one either sees “total darkness” or “extreme light.” In Concrete Night, both lightness and darkness are built into the architectures of being as confining spaces of shadows that set us free us in the hope of dreams.

Concrete Night was featured in the Focus on Nordic Cinema at Film Fest Gent (2016).