With his latest film, Lucifer, Gust Van den Berghe tackles 17th century poet and playwright Joost van den Vondel’s world-renowned tragedy. The filmmaker prefers to call his work a ‘cinematographic translation’ rather than a film adaptation. But what exactly is being translated, and how?

Lucifer (2014) is the closing piece of a film trilogy based on theatre classics. Little Baby Jesus of Flandr (2010) was inspired by Felix Timmermans’ En waar de sterre bleef stille staan, Blue Bird (2011) was based on Maurice Maeterlinck’s L’oiseau bleu. For each film the setting of the original text has been changed. In Lucifer Van den Berghe replaces Vondel’s celestial realm with the Mexican hinterland. The film was shot in Angahuan, a small village at the foot of the Parícutin volcano. The village changes from a place of paradisiacal peace into a living hell with the coming of a mysterious stranger: Lucifer, carrier of the light of good and evil.

THE FILMMAKER AS TRANSLATOR

In an interview with Belgian weekly Focus Knack Gust Van den Berghe characterized his films as cinematographic translations: “I’m not a storyteller but a translator. I try to translate a certain time into another, the same way a ferryman carries his passengers from one shore to the other.” Indeed, the German word Übersetzen or ‘to translate’ literally means ‘to cross a river’. In his essay Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers (1921) Walter Benjamin states that a literary work’s ‘survival’ (Überleben) beyond the fringes of its original language also implies a ‘survival’ beyond the fringes of time. According to Benjamin this indicates a ‘suprahistorical kinship between languages’: in its most radical form a translation makes the period in which a work was written accessible to today’s audiences. A translation essentially rests on the anachronism that makes an era materialize in another era. That is exactly what Van den Berghe’s filmic translation of Vondel’s Lucifer aspires to: not to carry the original text as such, but rather to carry Vondel’s era and its worldview from the depths of 17th century Counter-Reformation to contemporary shores. How does such a filmic translation work, and what exactly is being carried across?

The original 1654 tragedy – dealing with the jealous angel Lucifer and his battle for superiority over man – ends with Lucifer’s expulsion from the heavenly realm. The film on the other hand starts with Lucifer on his way to hell landing on earth, confronting a small, paradisiacal community with his knowledge of good and evil. That knowledge is based on a contemporary translation of Vondel’s theological and literary worldview, deeply rooted in an all-encompassing, circular and geocentric cosmology that was handed down to him from the Late Middle Ages. Lucifer is a cinematographic parable that illuminates the ‘survival’ of the central themes of good and evil, faith, doubt and redemption in our own contemporaneity. The film does not attempt to update Vondel or to make him more relevant but conjures up unexpected remnants of a pre-Copernican, circular worldview. In that sense, Lucifer turns us, albeit ironically, into Vondel’s anachronistic contemporaries.

BETWEEN HEAVEN AND EARTH

Lucifer’s anachronistic strategy permits Van den Berghe to ‘translate’ Vondel’s story to another time and another place. The nameless and remote village is portrayed as a closed community where old customs go hand in hand with Catholic religion and where the influence of Western modernity is hardly felt. Cut off from the rest of the world the town’s inhabitants are subjected to their self-proclaimed truths and convictions – verging on an almost naïve superstition. The only overarching means of communication is a megaphone, perched high upon a pole, operated through a sound system in a small store. The central and privileged position of this primitive mass medium, sending out its reverberating sound waves over the rooftops of the village, grants a status of truth to the proclaimed messages. ‘Attention, attention’ crackles through the speaker. ‘A ladder is hanging from the heavens. Look up, everyone.’ Fallen angel Lucifer (Gabino Rodriguez) – the ‘carrier of light’ – does not make his entry by land, but comes tumbling down straight from heaven.

The scene of Vondel’s Lucifer is laid in the strictly vertically organized hierarchy of the hosts of angels in heaven and even though the film is set entirely on earth, images, looks and storylines continuously glance upward, into the sky – as if the director is cinematographically investigating Vondel’s vertical world order. The town’s priest tries to ‘repair the relationship between heaven and earth’ by rebuilding a church in ruins. To justify this restoration of faith, he casts begging and praying glances to heaven, awaiting a sign from God. When the church is actually inaugurated at the end of the film, accompanying fireworks underline the renewed connection as an ironic reversal of the fiery act of God’s revelation.

Also, the destitute population of the impoverished village doesn’t seek salvation in the earthly powers or in humanitarian services but rather longs for a saving grace from heaven. In the film the Vondelian conflict between the heavenly and earthly powers is fought in the complete absence of those powers: just as mundane politics shy away from this forgotten community, God remains deaf to the prayers of the religious. The villagers are not medieval subjects ranked lowly in the cosmic hierarchy, in the bosom of God’s grace. They are hemmed in by the claustrophobic circle of their own mortality, yearning for the revelation that will ascertain God’s existence and his return among mankind.

Within this power vacuum, the jealous angel Lucifer sees his chance to enter the community disguised as a savior. The closed-off world of the film offers the diabolic title character an ideal playground. Feigned compassion and an aura of inviolability and moral superiority grant Lucifer the power to simulate miracles – a power he does not hesitate to exploit. The ‘miraculous’ healing of town drunk and self-proclaimed cripple Emanuel (Jeronimo Soto Bravo) sparks Lucifer’s self-aggrandizement. At the feast organized in his honor, Lucifer consummates his deification with an almost frightening indifference. Before promptly disappearing into the tar and sulfur of the volcano, Lucifer impregnates young Maria (Norma Pablo) and makes her grandmother Lupita (Maria Acosta) doubt her faith. In his wake, he leaves a battered and broken community that awakens the next day with the acerbic aftertaste of the apple of good and evil.

What then, makes this fairly simple story, permeated by naïve moralism, daring and provocative to today’s audiences? It is as if Van den Berghe, in radically advancing the strategy of historical anachronism, is making us believe that the Enlightenment never took place and that the cycle of life and death persists in an ever-recurring tendency towards heavenly salvation. As if today’s humanity is forever trapped in its longing for divine intervention. It seems like an outdated worldview but the ironic connotation – that Benjamin claims to be inherent to every good translation – makes it plausible. Playful references, like an apple heedlessly rolling by reminding us in passing of the Fall of man, help the contemporary viewer to reconcile himself to the ethical horizon of the tragedy.

SURVIVAL OF THE TONDO

It’s not just the ironic tone but also Van den Berghe’s daring visual strategy that adds to the contemporaneity of his filmic translation. In Lucifer,a circular filter transforms the usual widescreen format into a completely circular frame – an almost unheard of process in the history of moviemaking, barring a few exceptions in early and experimental cinema. Yet, from the outset, ‘raw’ optical images, as projected through the lens, are circular. Thus Van den Berghe’s round frame returns the film image to its optical origin and to the natural field of view of the human eye.

And there are other advantages to the round frame: cinematographer Hans Bruch Jr. developed a concave mirroring instrument that transforms the landscape, representing it as a world globe turned inside out. It’s much more than a simple optical effect. This ‘tondoscopic’ visual strategy serves the cosmological eloquence of the film: in this panorama the characters are doomed to a closed perambulation from which there is no escape. The centre of the image, coinciding with the zenith, remains inaccessible and empty. The divine is absent and replaced by the optical eye of the camera.

Nothing escapes this all-seeing eye: it suggests a film image that has no off-screen space at all, a world completely folded onto itself. Even the sound design contributes to this claustrophobic tunnel experience: Lucifer’s voices, sounds and music all emerge from the plunging, empty centre of the image. The image does not function in its width but in its depths. Thus Vondel’s vertical movement between heaven and earth becomes a tunnel-shaped connection between our natural field of vision and the circular frame of the film; like looking at the world through a monocular device. Whereas a rectangular film format retains the horizontal perspective we’re familiar with through our daily observations, Lucifer, quite literally, offers a global view.

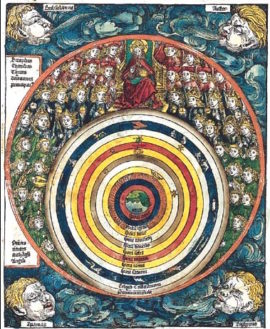

The oscillation between the tondoscopic opening sequences and the circular cropping in which the action unfolds, underlines the ambiguity of Vondel’s Lucifer as an allegorical figure of transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The circular frame brings to mind the ‘tondo’, a circular kind of painting the name of which derives from the Italian rotondo (‘round’). In the bourgeois Florence of the quattrocento the tondo became a popular form of domestic Andachtsbild, bringing the sacred atmosphere of the church into the secular atmosphere of the middle-class residence. The tondo’s round frame summons the ideal of higher perfection and can be read as a profane translation of the medieval aureole. By wrapping up the entire visible world into the geometrical perfection of a circle, that visible world is ‘sanctified’. At the same time the tondo embodies the humanist ideal of a paradise on earth. Thus, this circular painting plays a pivotal part in one of western visual culture’s most radical transformations. On the one hand there’s the aftereffect of medieval cosmological miniatures, representing the spheres of the universe in an all-encompassing circle under the eye of God and his hosts of angels, and on the other hand there’s the revelation of the middle-class aesthetic of the Renaissance tondo, making heaven impenetrable.

FILMING WITH A PAINTBRUSH

The same iconographic tension forms the core of Lucifer’s visual strategy. The tondoscopic scenes suggest a higher moral presence overseeing everything, but that impression is in contrast with the picturesque landscapes that bring to mind the so-called paysages moralisés of the Renaissance masters from the Low Countries. Also, Van den Berghe’sviews on humanity are no longer medieval. His images rather bring to mind Hieronymus Bosch’s famous tondo entitled Homo Viator. The panel depicts an allegory of the wandering man, the eternal pilgrim looking for spiritual security; uprooted and godforsaken in the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. He expresses a humanist ethics, permanently questioning the cosmologic coherence of the universe. This profane interpretation of the tondo format leads, both in Bosch’s and in Van den Berghe’s case, to an ironic turn that has the perfect shape of the circle clash with the humanist ethics of the narrative.

Lucifer might question our contemporary faith in man, earth and heaven, but its true merit is in its questioning of our faith in the power of cinema. By representing the Mexican landscape as a paysage moralisé enriched with allegories, Van den Berghe joins a tradition of Renaissance art inspired by humanist ideals – and with this anachronistic visual strategy he joins cinema to the history of painting. The friction between the sacred imagery of the Middle Ages and the humanist ethics of the Renaissance becomes a contemporary cinematographic problem that questions the potential sacredness of film itself. Balanced compositions, muted and intimistic sound design, countless musical fragments from the Renaissance, painterly vista’s, sfumatoof the slightly overexposed digital image, random references to the Christian aureola in close-ups of characters: in all of these stylistic choices an attentive viewer discerns the desperate search for an all-encompassing and sacred film image. The tondo’s survival on film is not just a formal gimmick, it becomes the theater of war between sacral and profane visual strategies. It supports the anachronistic translation of Vondel’s tragedy into a contemporary parable.

As contemporary parables should, Lucifer occasions a speculative proposal. What if Vondel’s worldview ‘survives’ in our time as a deeply rooted desire for salvation? What if Lucifer, bearer of good and evil, would show up today to once again divide a splintered society into two opposed moral categories; the Fall of man turned upside down? What if film, as a medium, would be capable of prying itself loose from the ties of a secular visual culture and what if it would harbor the ‘survival’ of sacred visual strategies within the limits of its technological instruments?

The surprising image at the end of the film, bringing back the magic of the widescreen format and returning the medium to its profane comfort zone, suggests that such a ‘consacration’ of cinema would ultimately be untenable. Lucifer, carrier of light, has never had a more ideally suited accomplice than cinema, the art form that catches light, transforms it and intoxicates us with its illusions in order to, finally, cast us back into reality.