These notes on this year’s edition of Cineteca di Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato are long overdue, over a month after the curtain fell on what was once again a magnificent edition. Seeing that the festival is now more widely covered in the press, it felt less urgent to share my impressions. By now, everyone who’s read reports on the festival knows that it was busier than ever. (Read the excellent recap in Film Comment to get a general feel of what Cinema Ritrovato is like.) There were more people attending and more screenings to attend. Admittedly there are some discomforts that can be linked to this increase in popularity, but nevertheless the exhilaration of attending a packed screening of a gorgeous print of a lesser-known early Hollywood studio film trumps everything else. “This is how these films were meant to be seen,” you keep thinking, whatever false assumptions such a feeling may hold. One facet of this sentiment does seem to have some wider validity however, one that Cinema Ritrovato inherently draws attention to. Over the last couple of years, the festival’s line-up increasingly included digital screenings, and this year’s edition was the first whose program folder featured small film reel icons to indicate which screenings were actual film screenings. This came as quite a shock, a wake-up call for the more willfully idealistic nostalgics among us. Our age is claimed to be digital; choices need to be made in the face of the dominance of digital projection, and not all of them will be very satisfactory. Something to think about, surely.

So, I really didn’t have a valid reason for neglecting the – mostly mental – notes I made during my week in Bologna. And after all, having the distinct pleasure of spending a week at what is arguably the most cinephile event on Earth is still a huge privilege, increased attendance or not. To boot, the festival celebrated its 30th anniversary and by golly, ’twas a reason to be jolly.

Which conveniently brings me to Jerry Lewis, whose 1964 slapstick romp slash industry critique slash autobiography, The Patsy (pictured above), was the first screening I caught at this year’s festival. (Lewis’ co-writer, frequent collaborator and longtime friend Bill Richmond died exactly a week before this screening. Read the New York Times’ obit here.) In it, Lewis plays bellboy Stanley who’s chosen to be groomed as a new star by the team behind a recently deceased comedian. Of course, his only qualification is simply showing up at the right time in the right place. Or, seeing it’s Jerry Lewis we’re talking about, at the wrong time in the wrong place. Classical Lewis shenanigans ensue, all depicted in glorious Technicolor. The latter is of course a hugely important part of Lewis’ comedic expressionism and the original – or vintage, as they call it in Bologna – 35mm print showed off how inventive Lewis and his team were in their use of color. The screening was part of a program strand called Technicolor & Co., which festival director Gian Luca Farinelli explicitly declared not to be against digital technology, but rather “intended […] to stimulate an informed conversation about the value of film stock prints and their restoration.” But we’ll get back to that.

Director of photography Wallace Kelley brings out the best in both sets and wardrobe, whose color design is less aggressive and more subtle than in better-known films such as The Nutty Professor (1963). Lewis’ mastery as a director goes beyond color however, and includes set design, sound design and especially staging, which is admirable in just about every scene in the movie, but attains brilliance in the scenes that really bring comedic performance to the fore.

In a sense, every scene in every Jerry Lewis movie is about performance, but in The Patsy he upped the stakes by not only thematizing performance in acting but also in story, script and direction. The story examines the comedy process and seemingly incongruously derives much of its humor from its main character failing to be conventionally funny. Lewis appears to be after demystification, with his emphasis on the construction of the star, the act, the hype and, in the end, the film itself. In truly modernist fashion, The Patsy ends with a reveal of the world of the movie – its spaces, its objects – as a set. Whereas in Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain (and similar examples), the construction is revealed by the camera-as-embodiment-of-the-director – the camera pulls back to reveal the film crew – in The Patsy the construction is revealed by the performer, through the (re)moving of elements of the set. Yet, however modern and interesting this deconstruction may be, for me the real value of The Patsy, and by extension of Jerry Lewis the filmmaker, lies not in the artificiality or in the reveal of the artifice, but precisely in that which is unescapably real: the physicality of the performance as staged and shot by the director slash performer.

The standout scene in this respect, is the one where Lewis visits a classical voice coach called Professor Mule-rrr (Hans Conried) at the latter’s sumptuously decorated house, filled with precious and fragile antiques explicitly forbidden to be touched. A commandment which Lewis of course can’t resist breaking. Several times he manages to avoid disaster, catching knocked over vases and statues at the very last second, nearly stumbling into various pieces of furniture and other valuable objects, only to have the whole place – ceiling and all – come apart at the end. All of this is presented to us in wide shots, highlighting Lewis’ excellent timing and agility, the fluidity of his movements, catching objects just before they would hit the floor and shatter into a million pieces. In this respect, the highly artificial setting is treated as something very real. The sense of seeing an actual act of physical ability never fails to cause a jolt of pleasure in me. Somehow, both the artificial setting and the materiality of the film projection heighten the sense of reality of what we see. It created in me the distinct feeling that I witnessed something real happening. I am fully aware that when stating this I’m probably influenced by the aphorism, attributed to Jean-Luc Godard, that “every film is a documentary of its actors,” or Rivette’s version, that “every film is a documentary of its own making,” but who am I to contradict those guys?

Watching Jerry Lewis, one of course cannot help but be reminded of Buster Keaton – whose face graced this year’s Ritrovato poster. The complete opposite of Lewis when it comes to facial acting, but never the less Keaton’s extraordinary fluidity of movement is obviously reflected in Lewis’ post-slapstick style, be it as if in a broken mirror. I only caught one of Keaton’s shorts, The Paleface (1922), brilliant as always, although on the less inventive and memorable side of the Keaton short film spectrum. The Paleface was presented in a new digital restoration, part of the ongoing Keaton project, an initiative of the Cineteca and Cohen Film Collection. Which brings me back to the materiality of film. Let me be clear: the restoration of many of Keaton’s films is an absolutely essential endeavor, especially since there aren’t that many good prints of Keaton films available. Testifying to this are the great many sources from which this restoration draws. Nineteen elements from five different film collections were inspected, four of which were used for the restoration, ranging from an incomplete first generation positive nitrate to a duplicate positive. There is no way such a monumentally important work can be unappreciated. However, at this point in my life, if I’m given the choice between seeing a good print of The Patsy and an excellent digital restoration of a Keaton film, I will always choose the former, no matter the latter’s greater artistic merit as a film. This is not to say that one is better than the other, just that they are two very different things. The digital image is a different beast, which holds less attraction for me. It seems less alive, it lacks the flicker, it lacks movement. You might think I’m nitpicking, sure, but these are the kind of things one is confronted with at festival as great as Cinema Ritrovato. Is it preferable to see a Keaton film where Keaton is actually discernible, where the picture’s contrast is actually an artistic element, rather than something that makes it hard to figure out what’s going on? Of course it is. But if time is running out for actual film screenings, I know where I will spend mine. And then of course there’s the strange fact that some films register more powerfully even on a battered print than on a pristine digital restoration.

Such could be the case for the rarity and oddity that is Who’s Crazy? (Thomas White, 1966), a film that was widely believed to be lost and hadn’t been publicly screened since it’s appearance at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival. It was filmed in rural Belgium, the setting for my childhood, and features a score by none other than Ornette Coleman. It’s basically a filmic representation of improvisational vignettes by the New York-based Living Theatre troupe, framed within a story of escaped mental patients. The story of the film’s survival is as wild as the troupe’s frenzied improvisations. The only existing 35mm print was moved between the consecutive residences of it’s director, in a large cardboard box. It ended up in his garage in rural Connecticut, where it rested for a long time, the movie unheard of except by a couple of jazz film experts. Vanessa McDonnell, an independent producer, tracked down the director by calling every Thomas White in the local phone registry and retrieved the print, which led to its restoration and the screening of a digital “print” at Cinema Ritrovato. The restoration was a success, and without it, it would have been impossible to see this curious film. However, its exultant transgressions, its focus on rituals, symbols and subverting natural order seemed to scream for being seen in flickering 35mm. Once again, the feeling of seeing something very real – the film feels like some kind of transcendental version of Godard’s aphorism – was muffled by the stillness of the image. It missed the spark of life that is always present in an actual film projection.

It should come as no surprise then, that my favorite program strand was the one that focused on the lesser-know films made during ‘Junior’ Laemmle’s stint as Universal’s head of production form 1928 to 1936, featuring a great many pristine archival prints form the Universal vault itself. The program was curated by Dave Kehr who noted the distinctly European flavor of Universal’s output at that time, the quality of which further contradicted any notion of Carl Laemmle Junior being nothing more than a fils à papa, if the famous monster movies hadn’t completely discredited that reputation yet. Filled to the brim with pre-Code goodness, this program was truly a joy to watch from beginning to end. Seeing these amazing prints, projected perfectly before often capacity crowds at Cinema Jolly – the festival’s least air-conditioned theater, which means something in the Bologna heat – one can’t help but think that this was how these films were meant to be seen. Or at least, that these are the best circumstances under which to see these film, minus the heat and the lack of oxygen of course. Elsewhere on this site, Anke Brouwers has written astutely and at length about the melodramas in the program, so I’ll focus briefly on two other standout films in the series, A House Divided and Laughter in Hell.

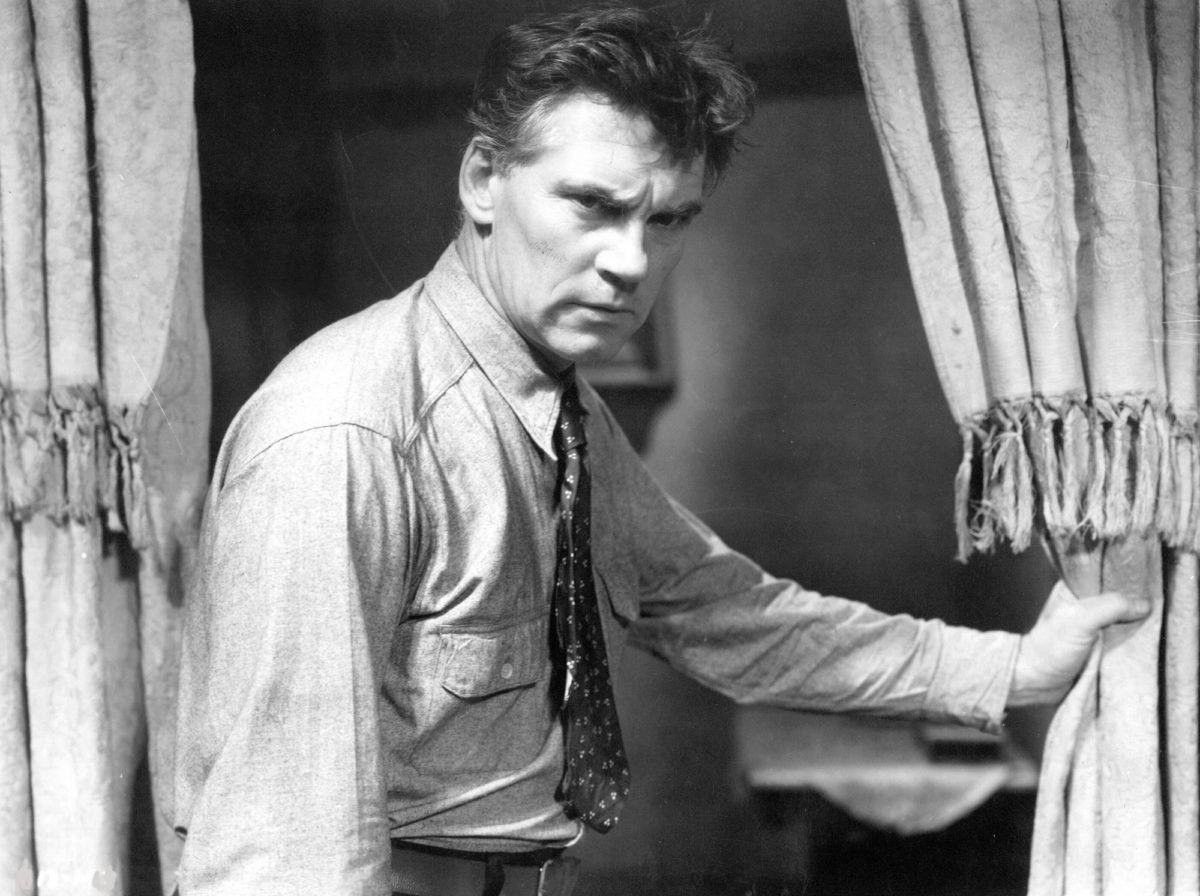

A House Divided (1931), starring Walter Huston reciting dialogues written by son John, is an early William Wyler film that bears all the distinguishing elements of his mature style. A stark drama, totally devoid of non-diegetic music, set on a remote island off of America’s Pacific coast, it features some brilliant staging in depth and inspired cinematography. Walter Huston’s towering turn as a brutish father who gets pitted against his own son, is awe-inspiring in and of itself but Wyler’s moody direction certainly brings out the best of his physically ferocious performance. The crown jewel of Wyler’s staging is his use of the staircase, arguably his favorite part of any décor. (David Bordwell has written extensively about Wyler’s style and his dramatic use of stairs in Little Foxes on his blog.)

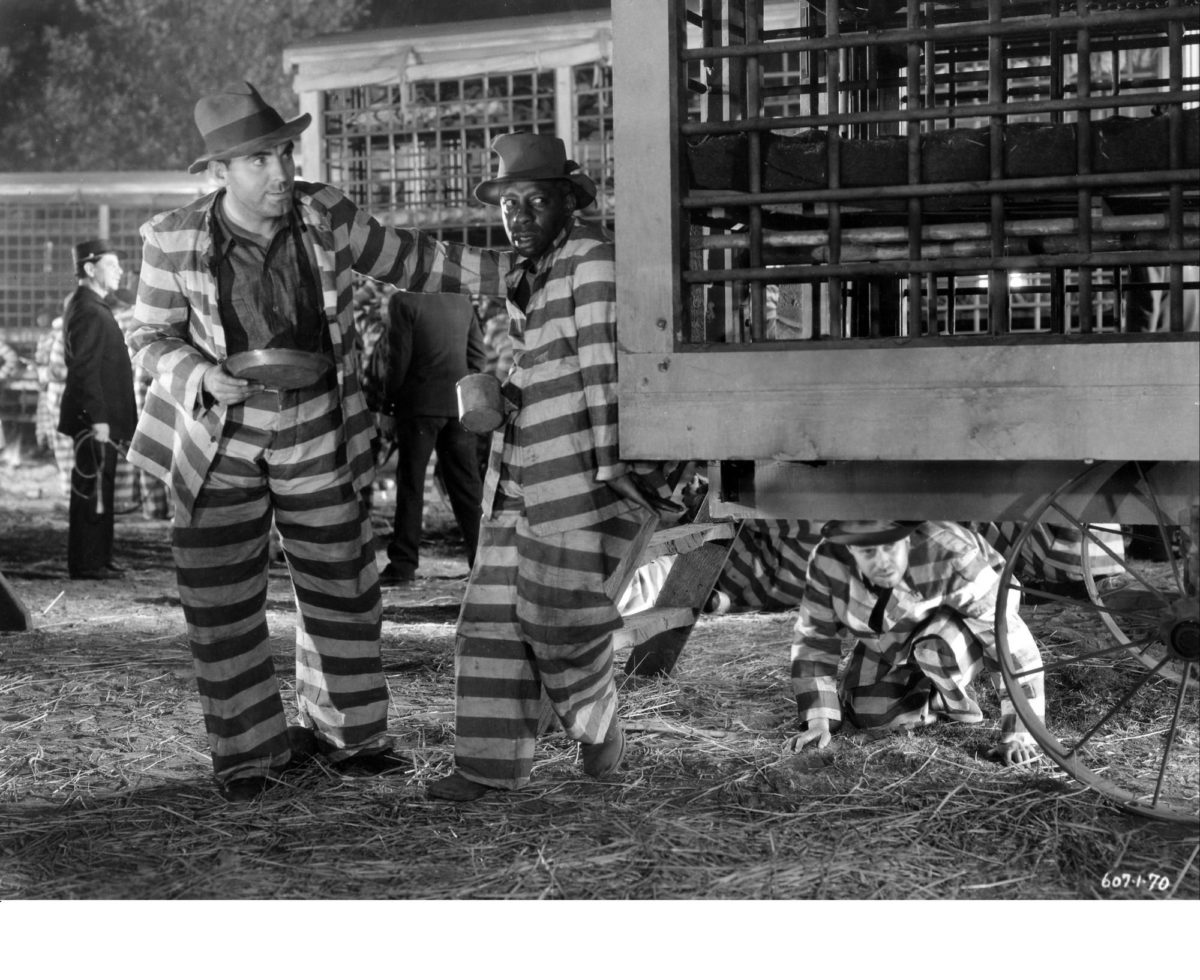

Laughter in Hell (1933) is something of an oddity. Part melodrama, part chain gang picture, its pacing and staging are relentlessly economic in its first part, rushing through a story of love, betrayal and revenge. It really finds its stride in the chain gang part, only to come to an abrupt and exquisite bitterly ironical end. Laughter in Hell was directed by Edward L. Cahn, who as legend has it earned his reputation from, as Dave Kehr writes in the catalogue, “his rapid re-editing of All Quiet on the Western Front, working in an editing suite set up on the train that was carrying the preview print from Los Angeles to New York.” Pat O’Brien is wonderful as the railroad engineer whose crime of passion earns him a place in a chain gang, oscillating between fury and despair for the duration of the movie.

Both of these pre-Code pictures share a bleakness and dark sense of humor that are also present in two brand new digital restorations of films from the same era, part of the festival’s Recovered and Restored program. Pat O’Brien reappears in The Front Page, the benchmark for all newspaper movies to follow. The first screen version of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s comedy gives preference to the ensemble of reporters rather than focusing on the Walter-Hildy pairing in Hawks’ masterpiece His Girl Friday, and even today the pre-Code naughtiness seems audacious for a Hollywood movie, ranging from sexual innuendo to flipping the bird. The Front Page, although widely available, was notoriously hard to see on a decent print or video copy, and to boot this restoration was based on an American domestic release print, a version which hadn’t been seen in decades. As was customary in those days, an international version was made for release overseas, containing alternate scene compositions and dialogue – more suited for an international audience – and lacking the aforementioned flipping of the bird.

Likewise, Tay Garnett’s Her Man (1930) was salvaged by its digital restoration. Part fateful love story, part Irish comedy, this lost gem shines thanks to its roving camera – tracking trays of glasses being carried around its dive bar setting – and over-the-top fight scenes. The film was restored from an original 35mm print in the Columbia archives, which sadly was a mess, riddled with scratches and having several scenes in the wrong order. The sound was taken from the optical soundtrack of original negatives in the Library of Congress. There still is some material missing however, resulting in some jarring jump cuts, but the overall result is nothing less than a resounding success.

So if there were any sense in keeping score, that would be two points for team digital, which scored again with the brilliant Jacques Becker retrospective. Il Cinema Ritrovato excels at bringing underappreciated figures like Becker to the foreground, as they had recently done with Jean Grémillon (read Tom Paulus on that topic here and here), and if it takes digital restorations to get it done, then hurray for team digital! Which brings me back to why I’m writing all this. As with every shift in movie consumption, be it video to DVD, or analogue to digital, some films get “lost” while others are “found”, as is the case for the incredibly beautiful Taipei Story (1985). We can only applaud that films such as Edward Yang’s masterpiece or the other examples mentioned above will be available to a wider audience, in excellent quality. At the same time we must not become too pleased too easily, as many films are threatened to be forgotten, or to suffer from sub-par digital transfers doing the rounds, with fewer screening prints or venues that can screen them available and not enough interest in or time and money available for restoring them. As I said earlier, choices need to be made, but not all of them will be entirely satisfactory. We do however need to be watchful that the scale doesn’t tip all the way to the digital end, especially where sub-par digital transfers are concerned.

In the end, it would be counterproductive to pit digital and analog against each other, whatever our preferences may be. After all, they are very different beasts. A good case in point here is the restoration of Westfront 1918: Vier von der Infanterie (G.W. Pabst, 1930), an impressively realistic early sound war film, whose turbulent release history left it relatively unseen for decades. Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek referred to this restoration as a simulation, an approximation of what the film looked and sounded like upon release in 1930.

A first attempt at restoring the film was made in 1988, based on a dupe negative – not the original camera negative, but a negative made from a print of the final edit of the film. Scenes missing from that negative were inserted from a poor quality release print. The second restoration started from a dupe positive (a positive image made from the edited camera negative), which had been exported to Britain in the 1930s and had been cut down for British release at the time. This time, the missing scenes were inserted from the dupe negative the 1988 restoration was based on. The result of this painstaking work is far better than what could be achieved almost 30 years ago, but as Koerber writes in his introduction to the film, “the result is compromised even after applying the latest digital methods.” Aside from the impossibility to recreate the film as it was because of the quality of the surviving film elements that were used in the restoration, the fact also remains that the end product is in itself a different object. It is this ontological difference that makes people like me choose analogue over digital. After all, a filmstrip contains an actual image, while a digital file is a set of numbers that can be translated into an image. Some might consider this fetishistic, but I believe that this tangibility, this direct relation to the real, is of great value.

This year’s Ritrovato coincided with the annual FIAF congress, which brings together everyone who’s someone in the world of film preservation and restoration. At the congress, Nicola Mazzanti, big boss of the Belgian Cinémathèque and local celebrity, delivered a keynote speech entitled ‘A Horse is a Horse is a Horse’, in which he likened the differences between film and digital to those between a horse and a camel respectively. To end this piece, I’d like to take his metaphor and run with it. A cinephilia that focuses on the history of cinema can hitch a ride on both the camel and the horse, just as it can find its object of affection on every type of screen, big or small. As Nick Pinkerton writes in his Sight & Sound piece on extended cinema: “[W]ho can say we aren’t living in interesting times? The idol of cinema has been toppled, and now its fragments are everywhere. And isn’t it terrible? Isn’t it exciting?”

It is both of those things, which makes the camel metaphor even more appropriate. The digital restoration camel is perfectly suited for navigating the repertory cinema desert we often find ourselves in. It can keep repertory cinema alive in circumstances that nostalgic cinephiles find less than desirable, and it can take it places it wouldn’t be able to reach otherwise. However, there are quite a few horse tracks still in business, places where we can revel in the joy of seeing actual celluloid projected in optimal conditions. Places like Cinema Ritrovato or the Belgian Cinémathèque, and many others. I firmly believe it is our moral obligation as cinephiles to do everything we can to keep the races going. Even if we have to place our bets on the odd camel every now and then.