At 125, cinema is still in its youth: painting is 40,000 years old. The oldest known melody dates to 1400 B.C. While photography only had about a 70-year head-start on moving images, it was enough leverage to be graciously allowed into the art world. Honest cinema remains the neglected child, under-loved by parents who wonder why it can’t be more like its siblings. Sometimes moving images wonder the same. As with time, the development of cinematic art is non-linear; nearly indiscernible connections in visual development of formal interdependence often span decades. To this day, the short form is widely unrecognized (outside of the avant-garde) for its possibilities, considered instead as a mere stepping stone to directing features rather than a specific form in its own right. In this sense, cinema still has a great deal of ‘coming of age’ to do. Medium-length films (roughly 30-60 minutes) are still scarce and virtually ignored by mainstream film culture when they do appear.

Over time the short form has proven itself more than capable of technical innovation while advancing the language of moving images—with and without sound. The 21st century has brought forth a stable of filmmakers who have developed an interest in the short form, tapping into its powerful potential. Historically, short films were a starting point for filmmakers in training, though many continued in that form. For avant-gardists like Gregory J. Markopoulos and Stan Brakhage, the short form became a consistent framework within which to develop conceptual elaborations of montage and manifestations of the mind’s eye. Regular feature-length filmmakers like Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet would semi-regularly return to uncommon runtimes of an hour or less, as well as ideas best suited to those shorter durations. One specific work by each filmmaker seems a particularly fitting representation of furthering their personal pursuits in cinematic language within the framework of a coming-of-age themed short film: Christmas U.S.A. (Markopoulos, 1949), Desistfilm (Brakhage, 1954), and En rachâchant (Straub-Huillet, 1982)En rachâchant can be watched for free on Vimeo, courtesy of Grasshopper Film: https://vimeo.com/246288299.

As it was Markopoulos’ third film, Christmas U.S.A. was fittingly shot on 16mm, after shooting his first film A Christmas Carol (1940) on 8mm—typically the format of home movies or amateurs gaining their footing with celluloid. His second film, in three parts, Du sang, de la volupté et de la mort (Of Blood, of Pleasure and of Death) (1947 – 48) was his first experience shooting on 16mm. Markopoulos claimed “that the language of film was in constant birth within me, myself as filmmaker.”Film as Film, Markopoulos, pg. 60

Reversing this ‘ordinary’ pattern of development, Brakhage shot his early shorts on 16mm, and stuck to the format until 1964, when he began to employ 8mm for his Songs film cycle. Straub-Huillet often shot their short works on 35mm, the format most commonly used on major motion pictures.

Why bother with variegated film stocks, visual grammars, or runtimes? As Brakhage put it:

“I am dreaming of the mystery camera capable of graphically representing the form of an object after it’s been removed from the photographic scene, etc. The ‘absolute realism’ of the motion picture is unrealized, therefore potential, magic.”‘The Camera Eye’, Essential Brakhage, Stan Brakhage, pg. 23

How can we visualize a reproduction of an object short of photographing it literally? And taken one step further, how might one visualize emotions and thoughts for which there exists no physical object to photograph? Markopoulos, Brakhage, and Straub-Huillet all approached this question metaphysically, yet their results vary greatly in their portrayals of such elements which extend beyond the physical realm. For Markopoulos engaging with history could mean the rapid cross-cutting between physical (albeit empty) spaces (currently lived-in apartments or 19th century castles) and historical objects (such as portraits, pianos or even strips of celluloid) as per Ming Green (1966, dedicated to Brakhage) or Sorrows (1969). For Brakhage it could mean a cosmic investigation of physicality on the scale of Dog Star Man (1964) or a manifestation of his own vision problems after a fall that resulted in eye surgery in Black Ice (1994). Meanwhile the materialism of Straub-Huillet meant that filming historical texts in modern times necessitated acting them out in a world which held no illusion of temporal transport—thus the traffic jams and architecture of the late ‘60s are visible in the background of scenes of ancient Rome in Othon (1969).

There was then and remains still much to explore, attempt and learn—playing with film stocks, visuals and runtimes are but three elements to be altered in the pursuit of the potential for magic. As an echo of how to find and present such magic, Markopoulos noted, “There can be no hope in what is called research itself; research is only evident at the precise and never calculated moment when the filmmaker decides to be a filmmaker, and takes the materials in hand and begins his work.”Film as Film, Markopoulos, pg. 61 That is to say, the furthering of formal film aesthetics largely stems from intuition—developments will only be made by those artists willing to delve into the unknown.

Christmas U.S.A. is a film that I put off watching for too long, expecting the missteps of youth to noticeably separate it from later works I have managed to see from Markopoulos. I was pleasantly surprised at being proven wrong. Not only had I confused the film in my memory with his first short, A Christmas Carol (although it was referred to by GJM as The Christmas Carol in some instances, all other official records opt for ‘A’), but there is a surprising technical competence to this short, considering its maker was only 21 at the time. We crosscut between a circus, and a young man waking up, shaving, preparing to go about his day. He receives a telephone call—a message from the other side? A remembered (or dreamed) alternate reality colliding into the present lived experience, culminating in a sexual self-growth spurt when the actual self and idealized self meet, and our protagonist gains the gumption to leave home, and with it, his well-meaning but overbearing conservative parents. The climax, which sees the two ‘selves’ meeting, takes place under city viaducts [pictured left]—visually echoed in another coming of age short, Brakhage’s Interim (1952) [pictured right]—where a couple initially meets and eventually separates. The final shots see him in his coat, descending the stairs to his mother and sister’s frightened stares of disbelief.

Though we as an audience are not entirely sure of what we’re shown, Markopoulos is certain in his stylistic choices of what he is showing us, carefully blending dreamed and actual realities, following Maya Deren’s lead with Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) [pictured left], six years prior. In fact, Deren’s image of a man’s face cracked apart as a mirror with a beach seen through the hole reappears in the similar crumbling of the protagonist’s face—as if made of glass—at the conclusion of Markopoulos’ Twice a Man (1963) [pictured right].

With Christmas, U.S.A., we are invited to examine another kind of break from social structures, as the young man leaves home. This departure is both literal in a narrative sense, metaphorical in his exploration of personal sexuality (in this case, a highly taboo homosexuality), and metaphysical in the film’s exploration of visual forms beyond the accepted norms of the time. Leaving home is an essential step for personal growth. In cinema, this means leaving behind the ‘safer’ formal choices of the day to explore the unknown.

It is this filmed departure from the domestic space that sets up Stan Brakhage’s fourth film. In Desistfilm, teenagers smoke. Yes, they’re having a party, but Flaming Creatures (Jack Smith, 1963) or Chumlum (Ron Rice, 1964) this is not. The free love of the coming decade’s sexuality is not even hinted at here, for the characters of Desistfilm seem to know only desire, lust, frustration and anger. The young men all channel their gazes at the only woman in the room, the negative power of each stare manifested into camera movements catapulted with frenetic energy from eyes to breasts, eyes to laughing mouth. The men smoke. Everyone seems to be putting on the act they feel expected of them. She begins to playfully throw a ball of yarn. The soundtrack of unsettling hums gives way to a distorted piano, the score for a pan which sees one youngster digging into his bellybutton, another building a house of books which crumbles, and another lighting seven matches at once, fanned out across one hand.

When we return to the woman, she’s tangled herself up in the yarn, throwing it in the air like a cat. The soundtrack escalates to horror as a young man approaches her, catching the ball of yarn, and pulls her toward him. We see the shocked looks of the rest of the boys, mouths agape, as they watch the yarn puller kissing the woman, he and she somehow suddenly exposing bare shoulders to the world in medium close-up. When we see the crowd again, they are still watching intently, but have managed to close their mouths. This is about two-thirds of the way into the film.

As for the rest of it; their embrace seems to drive one onlooker into a frenzy, running circles around the room until the rest of the boys toss him onto a sheet, use it to launch him into the air and onto the floor, and the whole gang goes running wild into the woods. The pair are briefly left to embrace in peace, though the soundtrack and warped view of the couple through a glass bottle suggest anything but. The glass falls and—presumably—breaks, the couple is shocked, and the camera shows our lost boys have returned to leer. That’s the film. Personally, I see next to nothing of the Stan Brakhage I know and love in this work, yet it plays a crucial role in his coming of age as an artist. Here he has already developed beyond controlled attempts at psychological realism, beginning a path toward greater expressionism. In a sense, Desistfilm demarcates the beginning of Brakhage the explorer, camera careening and vibrating as if operated by a madman.

Unlike Desistfilm and Christmas U.S.A., En rachâchant is far from Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s first film. In fact, it is sandwiched between their two major pieces to kick off the eighties—Trop tôt, trop tard (Too Early, Too Late, 1980/81) and Klassenverhältnisse (Class Relations, 1984)—and was preceded by two decades of intensive and demanding ‘literary adaptations’. En rachâchant is adapted as well, from Marguerite Duras’ children’s tale Ah! Ernesto (1971). Everything begins well and as it should be in the domestic space: the mother prepares dinner until the silence is broken by her child singing, “I shall not go back to school anymore.” Ever the economists, Straub-Huillet condense interactions which happen across time in the written story into a single pan—an excellent example of adapting from the page. A wide lens pivots perfectly from left to right, revealing the source of the singing, and beside him his father, reading the newspaper and smoking a cigarette as he asks, “why?” “Because at school they teach me things I don’t know,” the boy replies, still singing. This alarms the father, who finally puts down the paper and takes out his cigarette.

His parents take little Ernesto to school, but the headmaster doesn’t seem to recognize the child. Again a condensation: in the source story, the parents first go to the school without Ernesto, but the headmaster doesn’t remember the child based on his description, so they return the next day with the child in tow. Ernesto asserts that the school refuses to be taught. Pointing to a photographic portrait, the headmaster asks, “Who is that?”

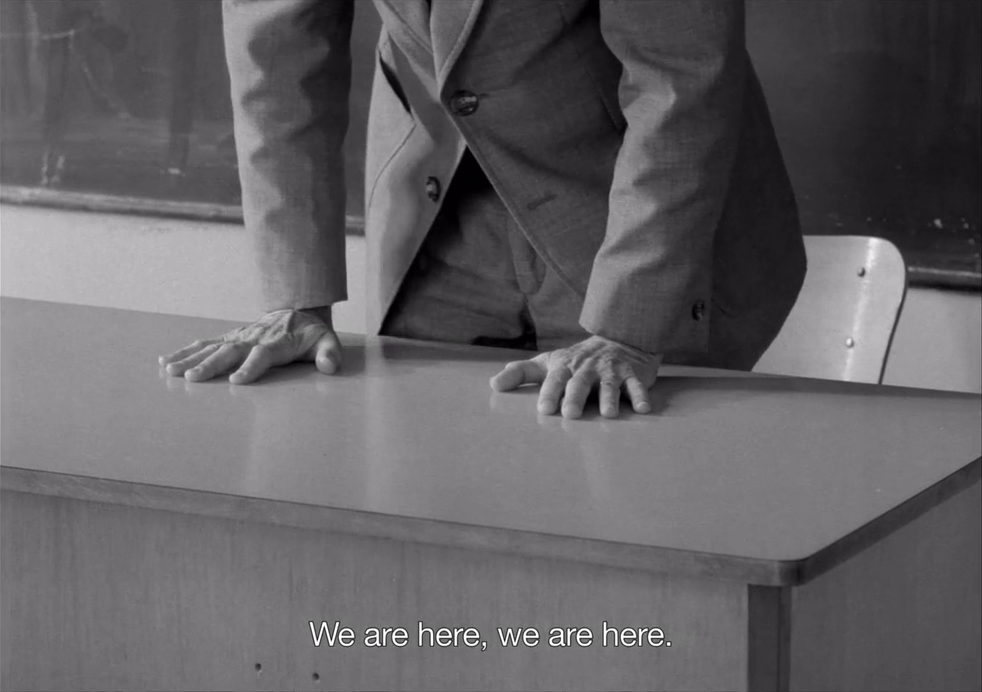

“A man,” replies Ernesto. When they repeat this routine with a butterfly under glass, Ernesto rebukes “a crime.” Playing along and clutching a globe, “And that, it’s a football, a potato?” asks the headmaster. Ernesto: “It’s a football, a potato, and the earth.” In a carefully spaced delivery, the headmaster notes, “So we find ourselves… in front of a child…who only wants to learn… what he knows… already.”

“Voila!” the father. When asked how he plans “to learn what he doesn’t know yet,” Ernesto replies only with the title, enunciated monosyllabically, “En ra-châ-chant.” When asked how, using his new method, Ernesto plans to learn to read, write, and add, he repeats his carefully styled separation of syllables, “in-ev-it-ab-le-ment” (“inevitably”). Shortly thereafter, he gets up and leaves his confounded teacher and parents to sort out exactly what it all means on their own.

Translating “rachâchant” online yields various alternate solutions: ‘spine’, ‘re-create’, ‘spit out’. When I asked my (native French speaking) mother how she would translate it, she said “repeating over and over.” Repeating over and over could sum up more than a few directors’ careers, yet the path that is repeated looks different each time. Indeed, Markopoulos, Brakhage and Straub-Huillet certainly advanced their film languages by ‘repeating over and over’. It is fascinating how well En rachâchant does and does not sum up the creative career of its makers. In—shall we say, relaxed—opposition to their signature Brechtian acting, Ernesto shows a playful confidence. He is assured of his position, and does not retreat an inch, absurd as his words sound to the adults.

All three films highlight the isolation inherent to being a younger person temporarily stuck in an adult world, and the separation in modes of thinking, as well as suffering. Yet Ernesto flips the tables to some degree; he’s not just different—he’s confident, and the formal elements of the film reflect that. So too does the young protagonist of Christmas, U.S.A. take his stand by leaving home. In all three cases, the filmmakers are Ernesto–artists forging new paths in education while being told they do not adhere to established logic, for in growing away from home, they have left the classroom behind as well.

“There is no language. There is no art. There is no knowledge. There is but film as film: the beginning and the eternal moment.”Film as Film, Markopoulos, pg. 79