Seven months before Bruce Baillie’s passing, I sat down to watch Castro Street (1966). His was a name I had often heard, yet failed to investigate. I was immediately awe-struck; it is a work that observes, with reverence and imagination, labor carried out on the titular street near an oil refinery. Rarely are images so invested in physicality and the concrete so whimsical and visually adventurous. While the lineage of such work traces back to the 1920s through titles such as Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Walter Ruttmann, 1927), the work of Joris Ivens, and theories of montage demonstrated practically in Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)—and can even be traced forward in time, such as to Dominic Angerame’s Continuum (1987)—nowhere else in this ‘type’ of filmmaking does one see the potential for hardened steel elements to stretch, for stiff lines to soften and congeal, as in Castro Street. Apparently inspired by Erik Satie, such fluidity makes perfect sense. Yet there remains a strict logic to the montage. For Baillie, superimposed images must inform one another, rather than simply clutter the page (and therefore the mind) as they so often do in the avant-garde; a moving train informs a static one, two trains traveling in opposite directions create a singular yet multidimensional and impossible object.

Six days before Baillie’s passing, I published a virtual film festival program (the third in a newly kicked-off series) curated by Michael Sicinski on Ultra Dogme. Sicinski titled his program ‘The Death Channel’, citing titles he “might like to see, just prior to experiencing the warmth of a more penetrating light.” This program ends with Baillie’s film All My Life (1966)—a single shot set to Ella Fitzgerald and Teddy Wilson’s rendition of the 1936 song of the same title. J. Hoberman calls All My Life Baillie’s “most extraordinary movie”. While Castro Street remains the one that got to me first, there is no arguing that what he manages to accomplish in a single, continuous pan is nothing short of miraculous.

On April 8th it came as something of a surprise to me when Dominic Angerame announced on the Frameworks e-mail list that Baillie was not in a good state, and that his wife Lorrie was in need of financial help, too busy working to give him proper care—that he was even sleeping on the floor for some reason. Two days later it was announced on the same mailing list that Baillie had passed, and that the donations received would be used for funeral costs.

I’ll try not to ‘make this about me’ to the degree that I am able, but as an experimental filmmaker, it’s hard not to look at the facts and wonder if—no matter how ‘good’ or ‘important’ or ‘influential’ one’s body of work might end up—I remain at risk of meeting a similar end lest I pursue more financially supported options. I have always considered that I had ‘my whole life ahead of me’, but even from my young age, I can’t help but start thinking ‘this is my life’ and rather than ‘ahead of me’, it’s right now.

Like Baillie, I believe art should be available to those interested in viewing it rather than hidden behind arbitrary financial barriers to maintain their perceived value; an ideal which faces considerable challenges in a world ruled by money. Every time I complete a new work I am faced with the conundrum of ‘how to release it’, knowing that a link on Twitter is as good as chunking a rock into space. Late in life Baillie maintained a YouTube channel which housed many of his works, free to watch in full—practically self-bootlegged when you consider that he was distributed by Canyon Cinema. Canyon was the first major experimental film distributor, of which Baillie was co-founder alongside Chick Strand. It was a particularly unusual practice for a filmmaker of his generation; even those who made the jump to digital portfolios and profiles tended to make only excerpts available to encourage paid rentals and screenings of the analog prints. (Ken Jacobs is another major exception to this rule.)

In October I was coaxed back into a cinema for the first time since the Berlinale ended in February. The program which convinced me to leave the safety of my home was one curated and presented by filmmakers Ute Aurand and Robert Beavers, as part of a loose ‘series’ in which they aim to engage younger audiences in experimental film. The flier said it was suitable for ages 6 and up—a brilliant initiative that we could use a lot more of, if you ask me. The screening began with a 16mm print of All My Life, obviously a substantial upgrade from the version available on YouTube, and beautifully battered—it even stuttered for a millisecond. Nothing quite beats the room-filling hypnotic fuzz of old-school analog sound. In between titles, Aurand and Beavers would pause to ask the younger viewers in the room what had stood out to them about what we had just seen. Ute mentioned something which I considered quite revelatory: that the fence pickets panning by sort of resembled the piano keys being played by Teddy Wilson on the soundtrack. Visual-aural harmony.

Castro Street and All My Life seem to be the natural culmination of a style Baillie had developed throughout the previous five years, calcifying the natural Zen and earthy, grounded documentary of Mr. Hayashi (1961) and Here I Am (1962) into the headier, nearly-abstracted presentations of To Parsifal (1963) and Mass for the Dakota Sioux (1964). These adventures reach dizzying heights with Quick Billy (1971) before easing into simpler, diaristic experiments on VHS in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Quick Billy is a slow investigation of the animal kingdom, blended through pleasing, soft sounds and flourishes of deep color. It opens with pure light: a nearly white screen with edges of orange, set to the sound of an occasional bird chirp and the soft distant rumble of what might be ocean waves. The soundtrack languidly gives way to the sound of air bubbles created deep under water as the image gifts us orbs of refracted light, floating in a deep orange glow. This gradually extends into a deep blue, and concrete images become visible (however slightly): a horse’s mane; the still image of a lion stretched by a glass surface moving across it; and light glimpsed through fabric, generating a cosmic vision of an ordinary sunny day. Eventually waves crash through the layers of imagery. As the film continues, so does the interplay between the physical world and the many ways we might perceive it, between the unwavering solid elements and fickle flourishes of vibrant colors.

In his remembrance of Baillie, P. Adams Sitney notes that without Brakhage, Baillie never would have made the types of films that he did. Like Brakhage’s Dog Star Man (1961–1964), Quick Billy is a portrait of consciousness. Yet where Dog Star Man moves at a Mach 5 clip, Quick Billy plays out with serene patience. Where Brakhage relied on silence, Baillie uses a steady stream of natural sounds: flowing water, blowing wind, birds chirping—not to mention classical music and some narration. Their depiction of sexuality differs as well. Baillie presents us first with a hardly decipherable silhouette of a breast, and then the full-on clear view while he’s copulating. Later, soundtracked by a golden oldie, an extreme close-up of fellatio haunts the background of a stream of old school photographs, warped as they’re seen through what appear to be sunglasses.

There is narration of making donuts, describing people in the photographs. At one point, while we watch slow life unfold on a farm, there is narration of what we see alongside memories of three-hour breakfasts, overflowing with pancakes.

In form, Quick Billy re-vitalizes techniques from Castro Street of multiple exposures. Here various tigers are superimposed over themselves, and Baillie’s fondness for ‘organic’ distortions re-appears as well, in the image of a man extending, ghosting, and stretching, as seen through a manipulated glass.

Almost as if to say “this is how the same film might look if made 50 years earlier,” the finale bizarrely twists into an old-timey would-be silent western, sepia toned and without direct dialog, yet still maintaining the occasional voiceover. The music plays directly off of the image as in silent film, aping and amplifying the exact motions and actions of the actors, and broadcasting tone shifts, alerting us when there is nothing but playfulness, or danger. This coda comes complete with separate title card and credits.

In conversation with Baillie at a 2011 screening at the New Museum, Apitchatpong Weerasethakul called Quick Billy the “real Tree of Life.” And in regards to its ending narrative shift, Weerasethakul says of Quick Billy, “it’s a reincarnation,” a significant influence on his own Tropical Malady (2004) and its ending.

“In order to understand, one must become one with the other,” says Baillie.

In the late decades of his career, Baillie’s output slowed considerably, but his desire to innovate and challenge himself and the media he worked with did not. In P-38 Pilot (1990), Baillie coaxes beauty out of VHS footage by merely shooting a birdhouse through a foggy window and mesh. And while it does give way to digital manipulation, it remains the type of gorgeous distortion one simply cannot parallel in an all-digital workflow.

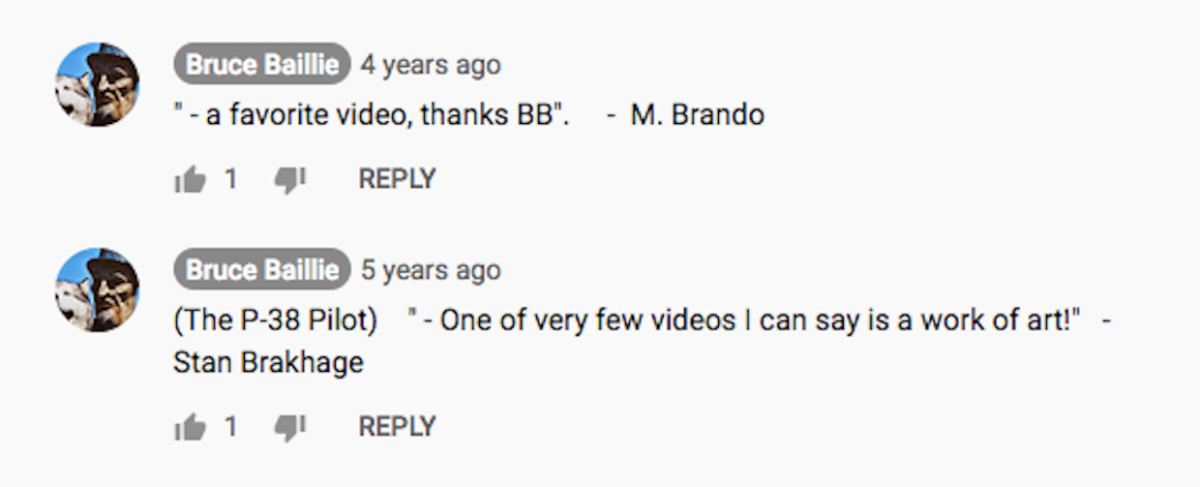

P-38 also includes two fascinating quotes, posted in the comments by Baillie himself:

Then there is The Holy Scrolls, an 11-hour archive of unfinished material, which supposedly has screened, though I haven’t been able to find much information about it apart from the 10-minute Introduction to the Holy Scrolls (1998).

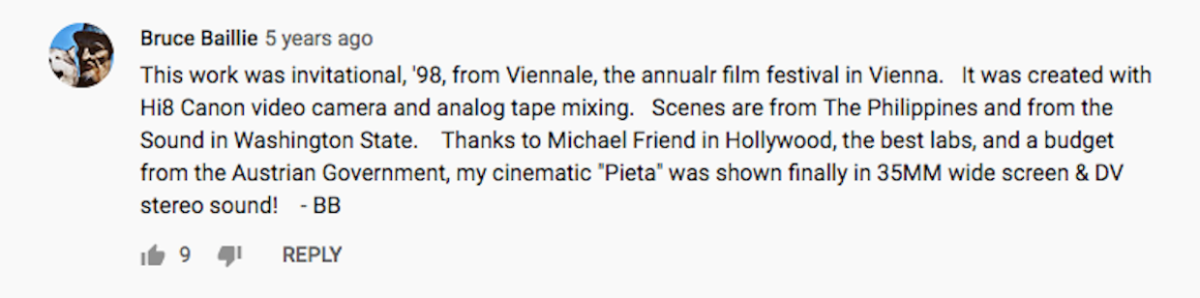

Finally, ‘all his life’ might be summed up by one final (one-minute) film: Pietà (1998). A trailer for the Vienna Film festival, it is one of the most profound compressions of childhood and the beauty of the natural world, and almost certainly the greatest one shot on Hi-8 Video. It can be seen here and includes a note from Baillie himself in the comments:

In losing Bruce Baillie, we have lost a folk hero and a visionary—that rarest of artists who simply sets out to do what they know they have to while entirely grounded, not to purposefully change the world, but sometimes accidentally doing so in the pursuit of simple pleasures.