Since then I remain a recollection, an absence; condemned to be your memory.

— Sur (The South, Fernando Solanas, 1988)

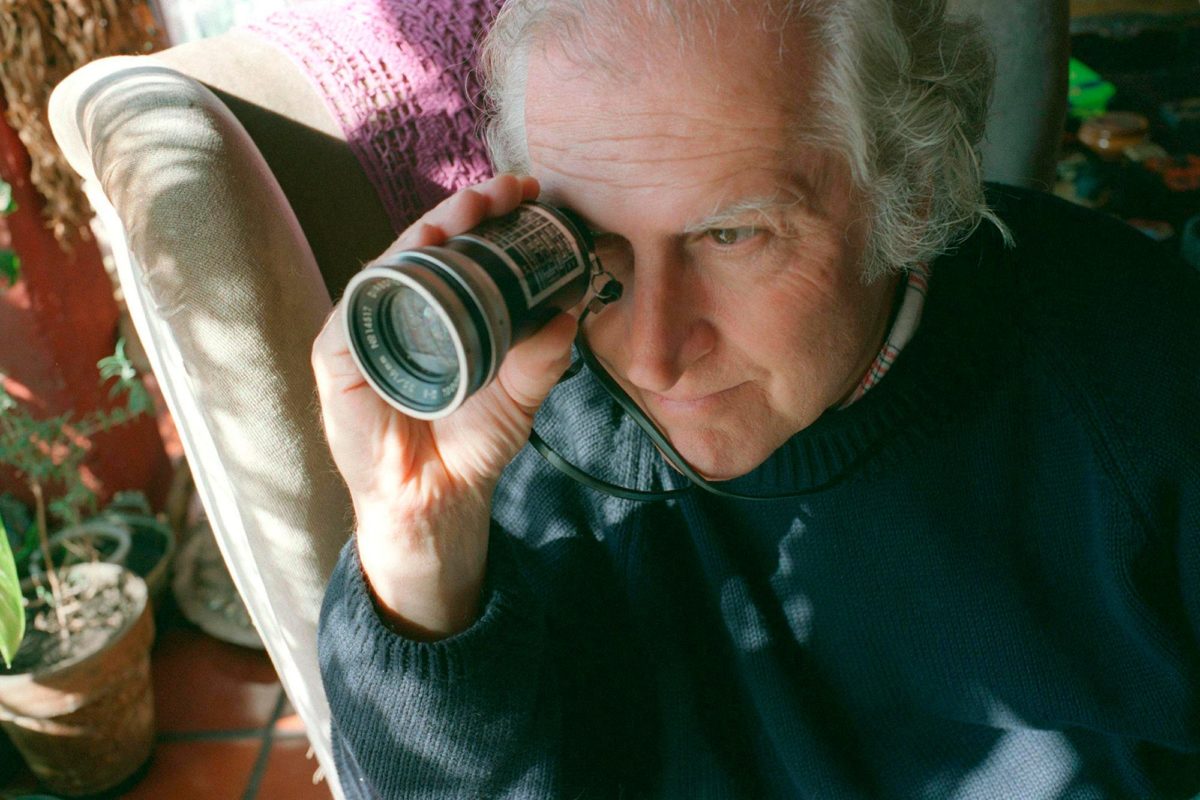

Filmmaker, politician, activist, writer. One could thoroughly recount any of these facets of Fernando “Pino” Solanas’ life and only scratch the surface of what really constitutes his legacy. Each role he had during his life came as a direct response to the state of affairs in Argentina and Latin America. There were moments for evocation and symbolism, times that merited a call to arms, and some instances when pushing for direct intervention seemed like the only way to really have an impact.

However dissimilar these approaches might seem, they are all tendrils of Pino’s greater project; small yet significant frames that when seen together showcase an ambitious bigger picture that can’t be contained within the confinements of a four-hour epic or a political stint. No matter how inventive he was as a filmmaker, or how integral his career in politics was for putting forward his principles, the resonance of his life-long commitment to the vindication of working-class struggles can only be grasped when all is seen in conjunction.

La hora de los hornos: Notas y testimonios sobre el neocolonialismo, la violencia y la liberación (The Hour of the Furnaces, 1968), his seminal work of activist cinema, famously stated that “in their rebellion, Latin American people regain their existence.” As a man whose modus vivendi meant constant revolt, Solanas was a living example of this. The political leanings in his works never aimed at subtlety, and still, they were always bereft of cheap demagoguery or half-hearted ideology. These were manifestations of a primal urge for change. Occasionally clumsy, constantly imperfect, but never without a beating heart.

In direct contrast with most of the self-proclaimed socialist expressions coming from Europe during the tumultuous 1960s, the drive behind Solanas’ incursion into the arts was not an intellectual one. Yes, he had studied theater, music and law during his youth, but the Argentina that gave him that opportunity was no longer the same once he was moved towards the moving image. Between his first short and eventual feature debut, he lived through two military coups and saw the de facto establishment of a right-wing dictatorship built on censorship, repression and neoliberal agendas. There simply wasn’t a place for abstraction or ruminations on “man as a concept” when students were muzzled by police batons.

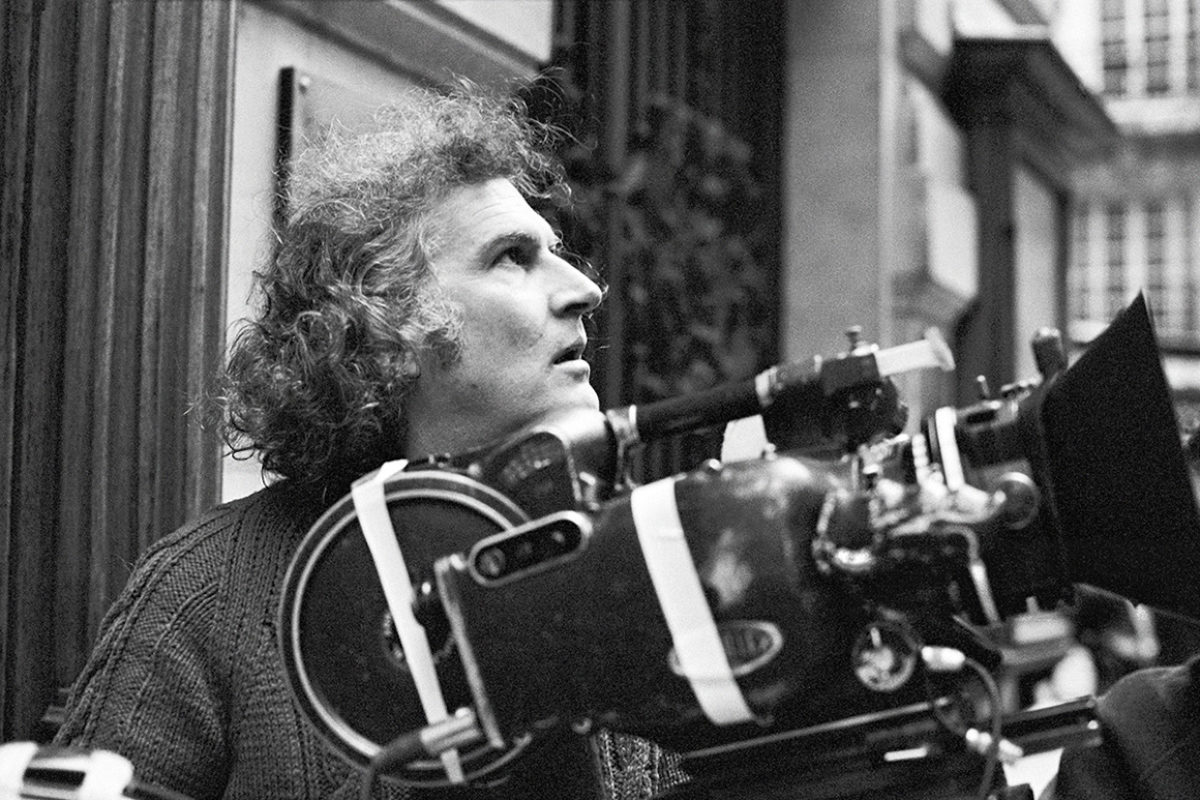

For Pino and his like-minded colleagues Octavio Getino and Gerardo Vallejo, cinema presented itself as a means for survival; a safety vault in which dissenting ideas and neglected memories could be registered and passed along. Rather than a consideration, creating became a need that exuded from every inch in their body, no matter the how’s and where’s dictated by canonical standards of production.

The hierarchy and detachment implicit in the role of a ‘director’ seemed counterintuitive to their goals, so it was rejected. They embraced being active parts of the world they recounted through images, and weren’t afraid to see it give back and permeate their work. Preconceived structures had no place in such an endeavor. This was vivid, marginal and dangerous, and precisely because of that, it felt crucial. When these filmmakers declared that “what’s real exists beyond the law,” they sought after it, even if it meant running a life-threatening risk.

The result was a paradigm shift that sent echoes all over the world, filmic and otherwise. Building on the work of fellow subversives like their Brazilian neighbor Glauber Rocha and his seminal ‘Aesthetics of Hunger’ (1965) essay, and first-world ally Gillo Pontecorvo’s ode to decolonization and resistance in La battaglia di Algeri (The Battle of Algiers, 1966), Solanas and Getino found their own clandestine ways to get their ideas across. It meant sneaking around, recording in the shadows and lying to those they held dear, which, in a context of persecution, seemed like the path to get away with the kind of provocation they were stealthily manufacturing.

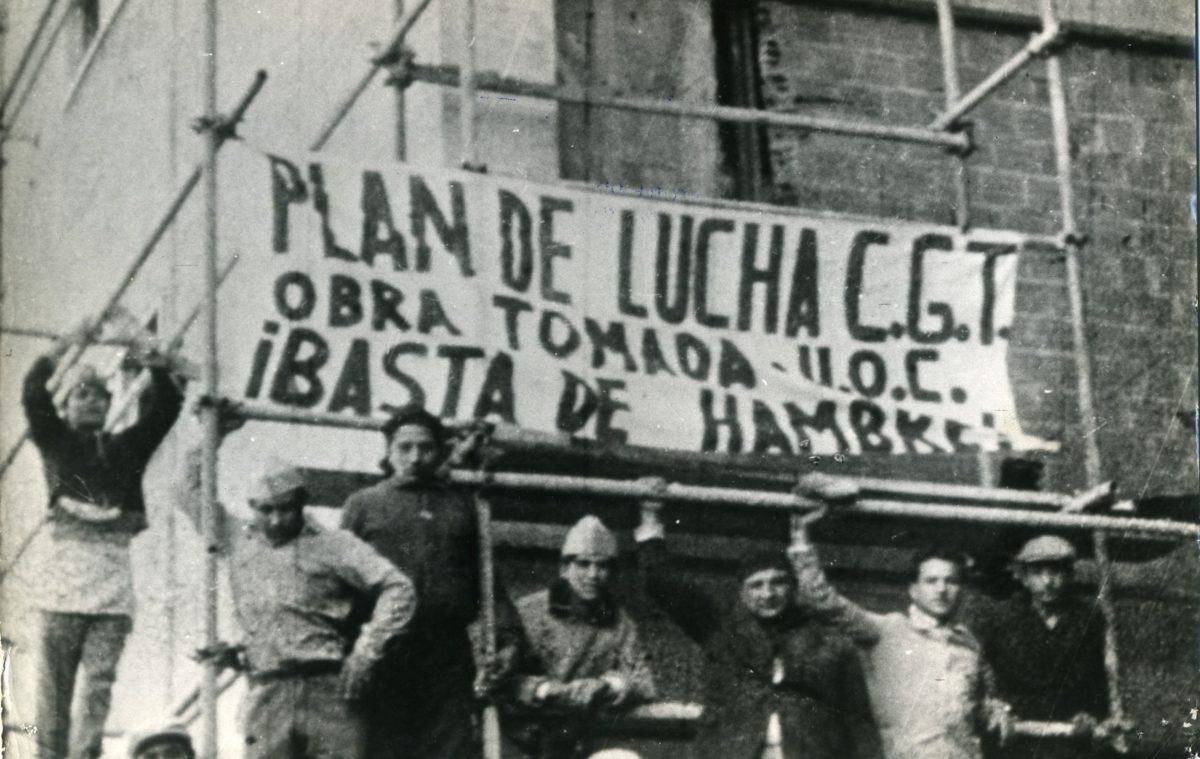

What they made, was The Hour of the Furnaces, a work so integral to the history of radical cinema and to the understanding of this particular moment of thunderous uproar in Latin America, that it transcended its intended aim and infiltrated some of the same circles of bourgeois film discourse it was actively mocking (“every spectator is either a coward or a traitor”). In many ways, the academic interest in this four-hour epitome of agitprop kept it alive within the progressively narrower realms of contemporary cinephilia, but seeing it in a vacuum has also overshadowed the rest of Pino’s oeuvre, and in some instances, it has even reduced it to a socialist curio and a one-hit-wonder.

The Hour of The Furnaces has never been just a time capsule or an instrument for social protest. Solanas and Getino stood side by side with those clamoring on the streets, sharing their outrage and letting it wash over every frame of what they recorded, while simultaneously infusing the material with their own ideals. Their project could mobilize worker organizations and student groups, and it could also spark a debate as an essay on neocolonization and its death grip on cultural identity. It was a living manifesto on the democratization of moving images, a filmic collage that wasn’t out of place playing to history students with no interest in audiovisual language.

The ramifications of such a landmark film are to this day still widespread and vast, and the same could be said about how they were felt throughout Solanas’ life. He raised the banner with his essay ‘Toward a Third Cinema’ (1969), and immediately felt support coming from Cuba, Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, Pakistan and Senegal. He became an international emblem for Peronism and political resistance, and, as it goes in the chaotic timeline of Latin American history, that soon meant there was a price on his head.

Pino’s allegiances were inseparable from his art. His life itself was part of the project, and no death threats nor attempted abductions could make him back down. The powers that be in the Onganía regime threw him out of his motherland, so he reshaped his vision to effectively reflect upon what was happening from a distance. Even if involuntary, his exile became his new disruptive method.

As he showed with his poetic unraveling of Argentine popular mythology in Los hijos de Fierro (The Children of Fierro, 1974), the political weight of his films was not predisposed to literal representation. His rage expanded beyond the incendiary stir of The Hour of The Furnaces (1968), and now coexisted with melancholy and grief.

He read about the burning streets of Buenos Aires in cold and indifferent Paris. His sense of longing could find no better embodiment than the mournful melodies of Astor Piazzolla’s bandoneon in El exilio de Gardel: Tangos (Tangos, the Exile of Gardel, 1985), his self-reflective musical on how to maintain one’s grasp with identity while adrift. He made his symbolic imprisonment a literal one in The South (1988), exploring the displacement felt by a recently released inmate roaming directionless through the night in search of his long lost love. Just as in his beginnings, Pino made sense of his environment in real time; his camera still positioned in the thick of it all, only then the place he was looking to transform also lay inwardly.

As it became quite apparent in his fable-like El viaje (The Journey, 1992), Solanas’ use of allegory wasn’t as effective or as clever as intended, but it always came from a place of sincerity. The youthful sense of wonder of his impressionable protagonist seemed to reflect a newfound joy in the old radical. His fictional works let him go beyond the scope of singular socio-political topics and address the concerns he felt on a more emotional level, letting loose his inventive imagery and unorthodox use of satire.

After all he went through, his conviction for a better world remained immovable. His later years saw him intertwine his career in politics with a renewed interest in the documentary form, now focused on shining light on environmental issues. Even if less formally adventurous than his earlier, more subversive films, the empathic way in which Pino framed anyone who came before his camera remained unmistakably his until the day he passed away.

Solanas’ reluctance to settle forced the cinematic world off of its high horse. He dared to dream of something better and then acted upon that belief, no matter what pre-established rules he was breaking in the process. To him, film being something plural and democratic was not so much about insurrection, as much as it was a possibility to explore new ground and let the medium recover its much-needed urge for discovery. Pino understood that in order for art to have any resonance, it had to be like the neighborhood he described in The South: “the one that loves you and bothers you.”