“Is it in focus?” charismatic cult leader Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman) asks his follower-protégé-dupe Freddy Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), who is taking his picture with an authentic forties Crown Graphic camera. Freddy responds with an expression of world-weary insouciance (come on, really?), because photography – as we have seen in the movie – is one of the few things he actually can do with something approaching confidence (the other is mixing potentially lethal moonshine from paint thinner, dark-room chemicals and torpedo fuel). Freddy is a shell-shocked World War II veteran, a marine with post-traumatic-stress disorder who, rather than coming home a conquering hero, starts to drift from job to anonymous job, from migrant sharecropping to photographing happy families or august individuals in a snazzy department store. In this, he is a lot like Homer Parrish (played unforgettable by real-life veteran Harold Russell), the hero of William Wyler’s post-War social problem film, The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), who we see struggling to connect with his teenage sweetheart. And because of that department store, he also conjures up memories of another character in Wyler’s film, Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), the decorated Army Air Force Captain who, because of a severe lack of jobs for returning veterans, must go back to his old job working a soda fountain in a Sears. Like Derry, Freddy Quell learns in the course of the movie that his love has left him for another veteran. And like Al Stephenson (Fredric March), the last part of the central triumvirate in Wyler’s film, a former platoon sergeant who returns to his old job as a bank loan officer, Freddy has a hard time controlling his drinking and his anger.

Anderson has said that The Master is informed by a wave of post-War movies about returning veterans, mostly presented as villains or victims, many of which belong to the noir genre, movies like Crossfire, Cornered, The Blue Dahlia, The Fallen Sparrow, and some of which, Preminger’s Fallen Angel and Whirlpool, and Edmund Goulding’s Nightmare Alley, are centred on faux spiritualists. That The Master is at least partly a movie about the movies is something that we have come to expect from writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson, who burst upon the scene with Boogie Nights (1997) and Magnolia (1999), two films bursting at the seams with creativity and invention both borrowed and original. The problem with these movies, in my view at least, is their highlight-montage aesthetic, which tends to blur the character-based dramaturgy. That fault was largely remedied by Anderson’s follow-up, Punch-Drunk Love (2002), a movie conceived as an homage to Anderson’s father, comedian Ernie Anderson, host of the cult TV-show Shock Theatre, that was less flashy, less out to please DVD-generation cinephiles. Punch-Drunk Love, despite its flirtation with MGM-style musical romance, was a hard-to-like movie with a hard-to-like protagonist, so it makes sense that, this time around, Anderson chose to reference lesser-liked and lesser-known Altman-Scorsese movies: not Goodfellas but The King of Comedy, not Nashville but Popeye. By the time There Will Be Blood (2007) rolled in, Anderson had come of age, easily eclipsing Scorsese’s own brutal period movie starring Daniel Day Lewis that allegorizes the duality of greed and evangelism as the rock that America was built on. The Master is another allegory disguised as a small personal movie (or the other way around), another homage to his father, a War veteran struggling with the strain of re-adapting (if you doubt the importance of the father to Anderson’s filmmaking, just look at the succession of father-son dramas that starts with Hard Eight).

How had the shift occurred? How had Anderson’s movies become, well, great? I would argue that Anderson managed to overcome his, what David Bordwell calls, ‘belatedness,’ a sense of coming late, in his case both to the tradition of Hollywood studio filmmaking and the New American Cinema that revised it from the perspective of the European New Wave. Most filmmakers of Anderson’s generation suffer from this affliction, and it shines through in their constant allusionism. But whereas most of the young directors who got their start in the nineties and noughties emulate the great artists of the New American Cinema – Spielberg, Altman, Coppola, Malick, Scorsese, De Palma mostly – they seem to forget that these filmmakers were also trying to come to terms with the legacy of the great classical auteurs, Hawks, Ford, Hitchcock, Ray, Fleming, Minnelli. Part of the change in Anderson’s cinema is that he has recognized and thematized what you could call a ‘doubled belatedness.’ If all this sounds terribly postmodern, then so be it. All I want to say is that Anderson has brilliantly succeeded, in his last two movies, to stage a confrontation between classical and modern American filmmaking, triangulating the relationship by maintaining a conversation between classic movies and great books. These are ambitious, literate and literary movies, fully expressive of a new sincerity, but their weightiness is lightened by their self-consciousness as movies, as popular art. When Anderson adapts Upton Sinclair in There Will Be Blood, or Sinclair Lewis, John O’Hara or Robert Penn Warren in The Master, he does so by pointing out the similarities to the great Hollywood stories of Citizen Kane, Giant, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, creating parallels between the iconic characters of Dreiser and Steinbeck and larger-than-life Hollywood characters like Orson Welles and John Huston.

And while we’re on the subject of these titans of the movies: what bridges classical and modern Hollywood in Anderson’s balancing act is precisely the period in which The Master is set – the late forties and fifties were a time when Hollywood was questioning its old beliefs, was embracing (psychological and narrative) realism for both aesthetic and economic reasons. Expressive of this new turn to realism was Hollywood’s love affair with (left-wing) theatre groups like the Group Theatre, a trend culminating in the shaping influence of the Actor’s Studio on the re-outfitting of the dream factory’s star personnel. Several critics have pointed out that the relationship between Master and Freddy can be read as a variation on acting guru Lee Strasberg’s relationship to his students, and that the ‘processing’ treatment in the movie bears an uncanny resemblance to Strasberg’s emotional exercises (during the processing session that has Freddy walk back and forth between wall and window, Hoffman is rumoured to have said, “I feel like I’m playing an acting teacher”). Suffice it to say that Hoffman and Phoenix are both Method adepts and that they are having a blast in the movie playing around with the idea of the Method without losing its essence of emotional sincerity. Joaquin Phoenix’s incredibly odd but perfect performance, “a tangle of tics and urges” A.O. Scott has described it, has been compared to De Niro in Raging Bull, particularly the scene in which Freddy trashes a jail cell while Master calmly and methodically deals out verbal abuse in the cell next door. “Mr. Phoenix, his shoulders hunched, his speech barely intelligible, his face twisted,” Scott writes, “pushes his performance beyond the psychological gestures of the Method into a zone of pure, feral, improvisatory being.” When Phoenix moves “beyond the Method,” what his performance becomes is grotesquely real, theatrically honest, ironically sincere. Daniel Day Lewis did the same thing in There Will Be Blood, embracing the silliness and pastiche quality that seems inherent to Strasberg’s teachings by integrating in his performance a thematically salient but borderline mannered imitation of John Huston’s vocal rhythms and timbre. Anderson’s model for this style of acting, I would argue, is Kubrick, who pushed stars like Nicholson and Cruise to the verge of parody without losing their iconic expressive impact. The original behind this minor tradition of what you could describe rather loosely as Hollywood Brechtianism, is Orson Welles, whose huckster-personality and vaudevillian charm Philip Seymour Hoffman is constantly channelling in The Master.

That The Master is at least partly a movie about movies, has become obscured somewhat by the centrality of focus given to one, admittedly hard to ignore, aspect of its narrative: that the cult-leader-con-man-visionary Lancaster Dodd (he calls himself a philosopher, nuclear physicist and a human being) plays as a thinly veiled riff on L. Ron Hubbard, and that his generically labelled ‘Cause’ shares some its therapeutic practices and time-travel ideas with Dianetics or, as we know it, Scientology. I don’t know if Anderson deliberately set out to make a movie about Scientology, but if he did, The Master isn’t it. As Kent Jones has argued, if Scientology is part of the film, it is part of a much larger narrative that encompasses America’s love affair with self-actualization as much as with gurus and sectarian religion. If There Will Be Blood is Anderson’s Greed, as some overzealous critics have argued, then The Master is his Dr. Mabuse, to stay with the silent-allegorical context, a movie that pitches as core to the democratic experience blind belief, devotion and obedience (and Mabuse, in Lotte Eisner’s book at least, showed where that could lead). However, much like Lang and Stroheim, and like the characters he wants us to think about, Anderson is equal parts genius and huckster. Like their films, his allegory is essentially a human comedy.

But I was saying that the exposé/à clef part of the movie has overshadowed The Master being about the movies. Or has it? Just as much coverage as to the Scientology angle has been devoted to Anderson’s decision to shoot most of the movie in the large format 65mm film stock, a format only very occasionally revived and then mostly for particular special effects sequences (Inception and The Dark Knight Rises are cases in point). What is usually reserved for tech publications like American Cinematographer became a concern for the popular media: that Anderson had wanted to give his film the texture, the density, the super-saturated sharpness and sheen he associated with fifties movies shot in wide-gauge formats like VistaVision, movies like North by Northwest and Vertigo; that the techs had nudged him towards 5-perforation Super Panavision 70 instead; that he had employed the format in a weird way, electing to frame the film in an 1.85:1 aspect ratio instead of the wider 2.2:1 expanse native to it. Well, maybe that last point was reserved for the tech journals, but the point is that few critics have asked why Anderson went this route, taking a fundamental aesthetic decision as a mere polemical point against the digital revolution in cinema. The critical response to the movie has been overwhelmingly positive, but the reaction to the use of 65 has been split: detractors consider it mannerist overkill to shoot a feature on 65mm when you can get just the same result – meaning as sharp an image – if you shoot it digitally. Besides, only a small percentage of the movie’s potential audience would actually get to see it projected on 65mm. Most of us will see it as a 35mm reduction print or as a 4k digital projection. In my local cinema, I saw The Master in 4k. It looked fine though not spectacular (and they managed to get the framing wrong). And even if you did get to see it as Anderson intended, who would notice the finer-grained stock? Well, fans would, fans of either Anderson, film stock or 65mm. Although he had reservations about the movie’s plotting, David Bordwell was among the believers:

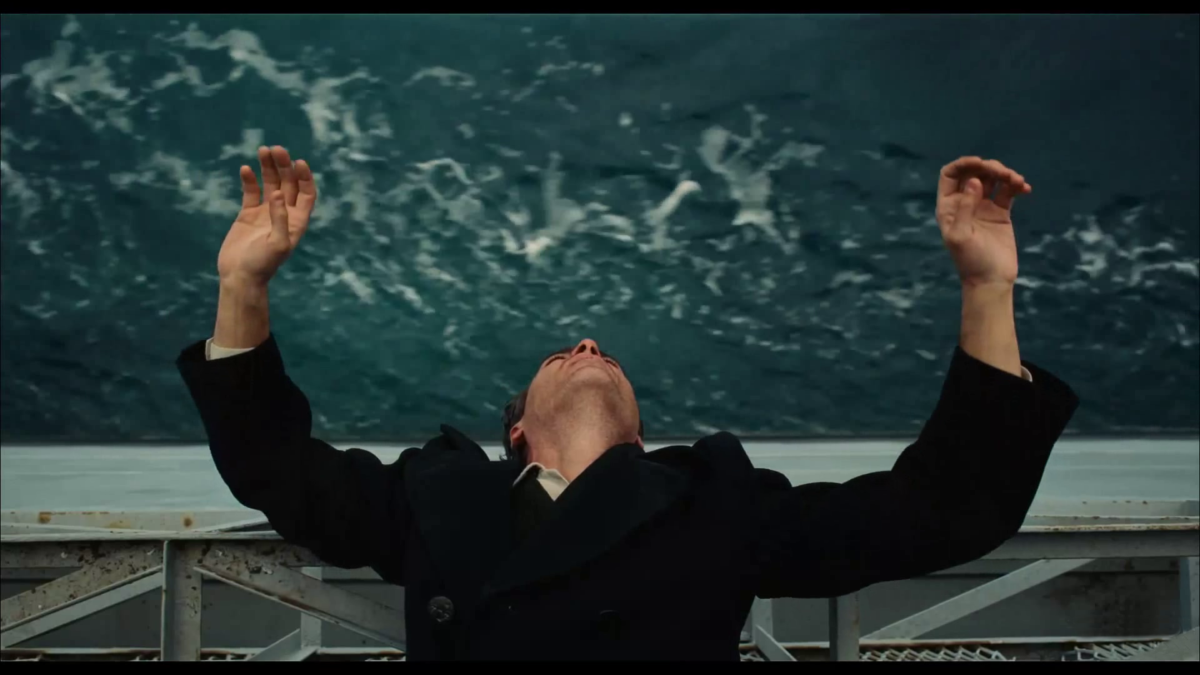

Sitting in the front row of Screen 1 at the Toronto International Film Festival Lightbox theatre, I was astonished at the 70mm image before me. Not a scratch, not a speck of dust, not a streak of chemicals, and no grain. So did it have that cold, gleaming purity that digital is supposed to buy us? Not to my eye. The opening shot of a boat’s wake, which will pop up elsewhere in the movie, was of a sonorous blue and creamy white that seemed utterly filmic. Now we know the way to make movies look fabulous: Shoot them on 65.

When The Master opened in Japan last week, Japanese director Toshiaki Toyodo took a solemn vow: “I vow, too, to film my next movie in 65 millimetres.” Seeing The Master on 70mm has become a cinephile’s wager, returning us to a time when you sometimes had to travel to see a movie at the exact moment it was playing somewhere, instead of merely downloading it (I did not join the Photogénie cinephile expedition to the Rotterdam Film Festival where The Master was to be screened on 70mm; the expedition ended on a downer because the print arrived damaged). The most entertaining of the skirmishes around Anderson’s decision to shoot on film in times of digital was signed Glenn Kenny and his perennial nemesis Armond White. You can find the whole thing here. What Kenny holds against White is not just the latter’s perplexing stance on digital but his alarming lack of tech knowledge, leading him to conclude that Anderson’s plentiful use of close-ups in The Master is completely opposite to the idea of 65mm cinematography. Kenny has a point, but he doesn’t develop it. Which brings us back to the question: why did Anderson decide to frame his movie in 1.85:1, the native framing of VistaVision that has become today’s standard Academy ratio? White implies that Super Panavision’s native aspect ratio of 2.2:1 is just too big for close-ups. But that’s discounting, say, Sergio Leone’s BIG close-ups in Techniscope, which has an aspect ratio of 2.33:1. In American Cinematographer, The Master’s director of photography Mihai Malaimare Jr. (familiar from Coppola’s Tetro and Twixt) said they went back and forth between 2.35:1, today’s standard anamorphic scope ratio, and 1.85:1, which Anderson felt was right for the period. Indeed, 1.85:1 was introduced as one of the first widescreen formats in the early fifties, the period that Anderson is dealing with in The Master. A more pragmatic reason is that Anderson originally planned to shoot only particular scenes of the movie in 65 and wanted to keep a consistent frame for both 65 and 35 throughout the movie. By cropping the 65mm negative with native 2.2:1 ratio (which was often projected at 2.40:1) to 1.85, the filmmakers lost the left and right sides of the frame. But given their emphasis on close-ups this matters less than in the case of widescreen directors like Minnelli, Mann or Preminger, who use every part of the frame. There isn’t a single shot in The Master that uses the extreme borders of the frame, so you won’t find a composition like this one from Lawrence of Arabia, shot in Super Panavision 70 and framed 2.2:1.

So why opt for a wider format when you are going to be shooting mostly close-ups?

Before tackling that question, allow me a short detour. In the spirit of Armond White’s detection of paradox in Anderson shooting ‘home-video close-ups’ in 65mm, J. Hoberman has called The Master “a panoramic chamber drama”. What is interesting about this nomenclature is that it opens up Anderson’s film to analysis usually applied to the rigorous and ascetic style of chamber piece auteurs like Dreyer and Ozu, or indeed Kubrick (Bergman and Altman are equally committed to chamber-art but less to its severe aesthetics). Given the restrictions imposed by setting the action in the relatively cramped interiors of the home, filmmakers exploring the aesthetics of the chamber piece tend to focus on exploring a number of set schemas and paradigms. One of these is lighting: as in the genre paintings by Vermeer and other Dutch masters by which these chamber pieces were either directly or indirectly inspired, light always falls on the figures from an adjacent window. This schema is exploited most extensively in the scenes set in the home in Philadelphia where Master and his acolytes temporarily set up camp, especially in the scenes with Freddy moving back and forth between window and wall during a new processing exercise, and in the scene when Dodd’s wife Peggy (Amy Adams) wakes Freddy in the middle of the night and the (moon)light shines through her translucent pyjamas from a window off-frame left.

In Lincoln, another instance of the panoramic chamber piece, Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski went all out in trying to come up with new and fresh variations on this classic schema.

Another important aspect of the chamber-art aesthetic is framing, especially as it relates to the idea of the tableau, the stable-space configuration that uses doorways and arches to create often quite complex layers of deep space. Since Anderson was celebrated mainly for his use of the mobile frame, for the showy Steadycam shots of Boogie Nights and Magnolia, it’s hard to think of him as belonging to the tableau-tradition, but it should be obvious that he devotes a lot of attention to laying out the space of his often quite lengthy shots (in this he is aided tremendously by the incredibly detailed period art design by Jack Fisk). The image under the title of this blog can serve as a an example, as can this image from There Will Be Blood:

The parameter or stylistic element Anderson most plays around with in The Master is focus.

Malaimare says that Anderson had the idea to try a larger format because when you think of iconic still photography from the period, you think of really shallow depth of field resulting from large format negatives. The idea was to shoot mainly portraits with 65mm, to reserve the format for “scenes when we really wanted to feel the depth-of-field as a strong point of the story.” But then they fell in love with the look of 65. Photography is a motif in the film, and Malaimare became involved in the film because of his love of portrait photography (that Crown Graphic camera Phoenix uses in the film is his). The three-point figure lighting Freddy employs in the movie refers back to the classical lighting scheme of the Hollywood studio film, which was somewhat disturbed by the arrival of new colour and widescreen systems: Technicolor was a slow stock that required a lot more lighting units than black and white, and when 65mm was commercialized during the fifties, the studio was similarly flooded with light to achieve the desired depth of field. Malaimare: “The slow 65mm stock has a voracious appetite for light, which gave The Master the feel of an old studio production.” The slowness of a larger-sized negative like 65mm film is complicated by the type of lens required: the larger you go qua film gauge, the bigger lens you need to get the perspective you want. In other words: a 50mm standard lens for 35mm would have to be something like a 100mm lens for 65mm. And, of course, the longer your lens, the shallower your depth of field. If you look at the list of classic 65mm films – Lawrence of Arabia, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, My Fair Lady, 2001 – only the latter uses relatively low lighting levels; the others are distinctly ‘high-key’ or, in the case of Lawrence, using a location with high levels of natural light. As you see here in two examples from My Fair Lady, the zones of focus are extremely limited (especially with the added day-for-night filters): notice how focus drops off quickly to the middle ground and edges of the frame in the first image, and on the foreground and background in the second example.

Let’s take as an example from The Master the scene in which we first see Freddy doing his job as a department store portrait photographer. The store – envisioned as a Mad Men-like paradise of consumerism – was built from the ground up in a vacant building in downtown Los Angeles. Malaimare explains they had floodlights blasting light through the windows and dozens of daylight-balanced lamps installed in the ceiling above the showroom floor where Amy Ferguson, as a store model, makes her unforgettable entrance in a swooning long take set to Ella Fitzgerald’s “Get Thee Behind Me Satan.” But even then it was hard to get any depth of field. The image you see her is a screen-grab from the trailer; it’s all I could get, but even here you see how only a single area of the camera view is in focus.

My question is: did they want depth of field? The luscious, dreamlike quality of the scene, and much of the movie as a whole, depends on the severely limited depth of field – especially on big close-ups taken at low light levels – you get with 65mm and widescreen formats in general: only Ferguson is in focus, the rest of the world is a blur; only when someone comes into her ‘zone’ they become part of this sliver of focus. Given that Ferguson is on the move throughout the scene, this is a focus puller’s nightmare (focus puller Erik Brown said he played largely by instinct since there was little or no blocking beforehand; playing by instinct was something he had picked up from working with Terrence Malick and Emmanuel Lubezki in similar circumstances on The Tree of Life). A beautiful instance of pulling or ‘racking’ focus, switching between a sharp and a blurred plane, is when Freddy catches sight of Dodd’s borrowed yacht, seen first as a defocused plane of glittering colour blots, then thrown into focus. Again, the effect occurs in a moving shot.

Selective focus is highlighted throughout the movie, as these examples illustrate in which focus, even in medium shots, is on a single figure or plane:

By referencing the extremely shallow depth of field in portrait photography of the period, Malaimare is merely stressing the importance of the tropes of photography and portraits in the movie. The unwritten law of shooting a movie close-up is that you open up the lens and use long lenses to blur out the background so the viewer’s attention stays on the speaker only. The Master plays around with this convention – using a 300mm (!) lens for most of its big close-ups –sometimes sinning against the rule that the character speaking in a close shot should always be in focus. So the question, “Is it in focus?” becomes more than an in-joke and quite salient in regard to the movie’s aesthetic.

To conclude this part, let’s point out that Anderson, like Kubrick, loves to exploit extremes of lens length, both long and short. For the opening scene of Freddy enjoying some R&R with his fellow seamen on a Pacific island beach (a scene highly reminiscent of the opening scene of Malick’s The Thin Red Line, although the homo-eroticism is Anderson’s alone), Panavision provided a special 19mm lens. In the shot below you see how the angle with the camera positioned low to the ground, accentuates the distortion effect on the straight lines near the edge of the frame, the poles of a canopy on the beach bowing outward. This effect is an exaggeration of the already drastic distortion produced by the shorter lens in classical widescreen processes.

The flattening effect of the long lens, squeezing planes together, is illustrated in many of Anderson’s characteristic ‘planimetric’ images lining up parallel planes perpendicular to the lens axis.

Next up for Anderson is the adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, which will again star Joaquin Phoenix. It’s unclear whether Anderson will be working with Malaimare on this film, or whether he will resume his long-time partnership with Robert Elswit. In any case, the selective-focus look of The Master would be perfect for Pynchon’s stoner noir universe, as another master cinematographer, Roger Deakins, has shown in a classic scene from the Coen Brothers’s A Serious Man, showing a young boy’s stoned point of view during his bar mitzvah. For this shot, Deakins used the tilt lens, a lens originally built for still photography that changes the plane of focus. As in much of The Master, focus is on the same narrow plane.