‘Rage, rage against the dying of the light.’

Dylan Thomas

To the Spectator

Lose the body/without oneself

Darkness. To lose the body. To forget one’s material existence completely only to find the body once again. The desire to have been blind beforehand, to erase one’s memory and be entirely alone and without expectations.

No medium allows a spectator to be as completely disconnected from one’s reality and body as film. It offers the opportunity to be completely without oneself. In consequence, the cinemagoer is never part of an audience. Cinema is experienced in solitude. The solitude and the loss of the body stand in direct opposition to the experience of other art forms. The presence of the spectator’s body as well as the artists’ is central to theatre and performance. The space is fundamentally shared. Not in cinema. Film is anti-interactive and anti-empathetic. Cinephilia is solipsistic. One mustn’t touch or be touched while watching film. One mustn’t be talked too. Cinema comes into being between the screen and the spectator. In this process, one’s place in immediate reality must momentarily be suspended. Anything that may disturb this unilateral focus must be removed to keep intact the cinematic experience. While recent work in spectator studies has emphasized that this ‘dyadic relation between individual viewer and film is an artificial reduction [since] the collective constellation is always a triadic one between viewer, film, and the rest of the audience’ (Hanich 7), I personally feel this emphasis on the social or communicative aspects of cinema-going to be misguided; the attention given to it disproportionate to what the cinema experience effectually is. I adhere to the idea that the ideal viewing situation is one in which the viewer is largely oblivious of or indifferent to the presence of other spectators.

The desire to have been blind beforehand. A desire to erase one’s memory of all previous cinema, of more than 100 years of cinema; to erase one’s memory of all other art, culture and philosophy. Nothing should remain. Annihilate all platitudes, clichés, types, Hollywood in its entirety, ideas, high and low culture. A post-apocalyptic film—post-apocalyptic in its materiality, not in its subject matter. In fact, why not eradicate subject matter. This eradication is only possible through a hushed, invisible accumulation of all previous ways of seeing. The experienced tabula rasa is the result of a complete understanding of the medium and all its previous expressions—not necessarily on the part of the filmmaker, but on the part of the film.

Neither the erasure of memory nor the loss of the body point towards a cinema of escapism. Cinema and escapism are irreconcilable.

Rather than escapism,

Movement/towards

Cinema is defined by an absolute movement that disrupts a film’s linear progress. It can be a single moment in a 9 hour film. A composition in motion that seems to at once expand in all directions and be drawn together in a central gesture, unified mid-action. The movement can be infinitesimal or monumental; a shaking eyelash or a mass migration. It can exist in silence or only come into being through sound. For an instant it effectively erases all that came before. This movement transcends the film in its entirety, yet derives its effect only from the construction surrounding it, which falls away at its emergence. Plot, mise-en-scène, acting and style all serve the realization of this cinematic movement.

Cinema, in this instant of movement, suddenly pulls at your core. The equivalent of a rush of cold water on a previously numb face; the equivalent of the first gasp for air after a deep dive. It divides one from oneself only to compel a return. The cinematic moment consists of two movements and the instant in which the one catalyses the other; the absolute movement on the screen and the pull one feels at one’s core, shifting you towards the surface and the originless energy it seems to have imposed. Immediately its source seems lost. A transfer of kinetic energy minus the collision: the cinematic movement urging you to move, be, act.

You no longer gravitate between the movements, instead

Finding the body/life once again

In between the movement on the screen and the pull towards it, lies the realization that the anti-present state of the cinemagoer imposes a gentle and self-inflicted death. Freed from identity and the responsibility to act in the world, to engage, the cinemagoer enters an Oblomovist state. This is a necessity. Only thus can one be reawakened and compelled to reclaim oneself, one’s life. Hence, the cinematic moment becomes the reconstruction of the body, the reinsertion of the body in life.

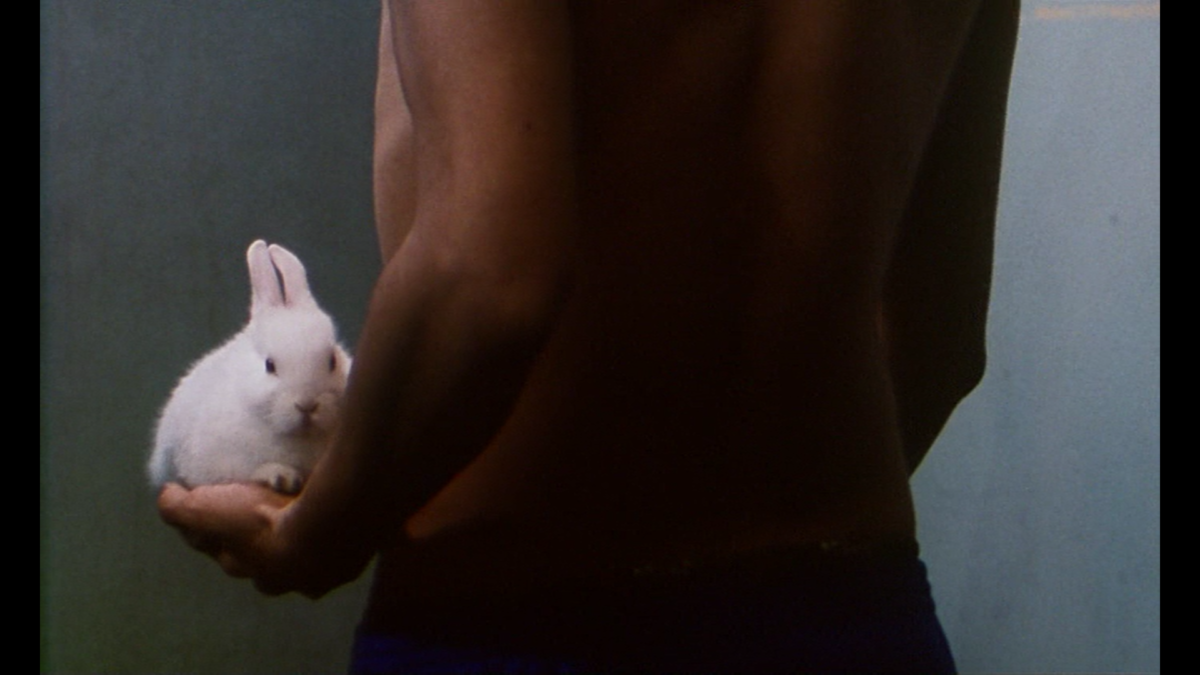

The cinematic moment acts as an impetus. With force it makes us attentive to the sensuality of our existence, our taking part in the world. It reasserts the possibility of movement, action, taste, life.

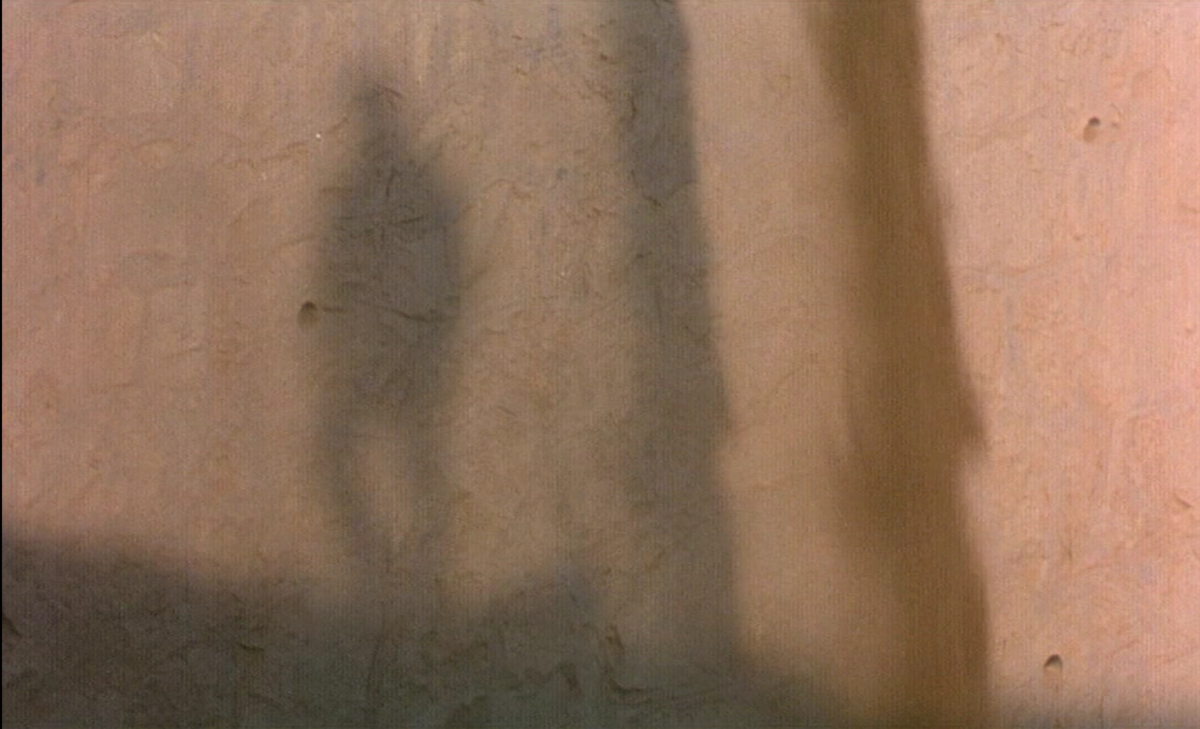

The essence of cinema is the blazing noon light falling onto your closed eyelids through the train window. The light pours through your skin, imprinting onto your retina ever-changing variations of bright coral in flashes, as the light is momentarily blocked by trees along the tracks, then, relentlessly, comes streaming, pushing forth again. The sight is simultaneously overwhelmingly dense and closed off, and translucent, a haze. Light in motion, the absolute minimum. A colour that is unidentifiable, non-existent besides in that particular moment. Light, motion, particularity: the materiality of life.

To the Filmmaker

Cinema must originate in a desire to recreate the moments in which life’s urgency and relentlessness arrests us—the light pouring through the eyelids. Moments that bring forth an impression of truth or insight into how we relate to our environments, others, ourselves, our bodies, our language, our thoughts, our complete and utter lack of comprehension. Occasionally, a confluence of mild paranoia and euphoria, the impression that all pieces of the puzzle are handed to us throughout our lives, that perhaps it is only sloth keeping us from a complete overview, enlightenment. The cinematic moment seems to tap into the residue of all the clues, all previous moments stranded in our memory.

The successful translation of these moments in cinema amounts to the opposite of sensationalism or escapism. Cinema revolts against banality, not through excess and fantasy but by recreating the small illusion of truth, which in turn becomes a truth in itself. Cinema is neither an instrument nor a product of ideology. Cinema creates idolized flecks of life by wresting moments from the cracks of the banal and infusing them with light, thus making life the ideology. Transposing some of the intensity of the human experience,

articulating the moment/rooting it in materiality

Cinema translates, articulates the absolute particularity of a given experience in such a way that it becomes intelligible to others. What the cinematic moment instigates is the recognition of something the spectator has never experienced, has not lived, essentially does not now and should not be able to understand beyond a cerebral level. The spectator experiences a type of primordial déjà vu. The cinematic moment has never been there yet has always been there. It forms the answer to an unasked question.

To achieve this, cinema becomes the reconstruction of the viewer’s body in a moment in which it was never present. This entails the creation of a relation to a hypothetical reality in its materiality. Through sound and image film must achieve the impossible, namely become physical, by imposing sense impressions in absence of their legitimate origins: the taste and smell of apricots, of skin after it’s been in the summer sun for hours, the texture of unfinished wood, spilled milk.

The strength of film as opposed to other media is that it (re-)places the moments distilled from life back into its fabric. Cinema is the worship of moments and the intricate and particular way they are woven into the fabric of everyday life, into life’s emptiness, the lack of memorability of its totality. Integrating these idolized flecks of life into a recognizable reconstruction of material reality, an elaborate, ideally synesthetic lie, creates the illusion of recognition that becomes actual recognition urging you to

act, be.

To the Manifesto Writer/ to Myself

All has been said.

All has been said.

To write an anti-manifesto!

To read all the other anti-, no-, non- manifestoes.

To write an ode to the cinema

(that is yet to be made)

To write an almost-ode, an ode-to-be.

Not to write

To not write

To wait/to be in waiting