A great film is one which cannot be done justice by linguistic means—a work which utilizes moving images in a way that cannot be fully translated to words alone, which does not merely turn a screenplay into a filmed play, and of which the best scenes often eschew dialog altogether. Moving images are interesting for their action (be it human movement, camera movement, the movement propelled via edits, etc.), an idea often summed up by the lackluster slogan “show don’t tell.” There’s truth even in this reductive phrase, but the greater truth has more to do with the ‘magic’ created by how you decide to show. To merely ‘show’, without any care taken as to how to show, is a surefire path to mediocrity.

How might one go about ‘telling how to show’? To an extent, there are some basic rules of visual grammar, such as the 180-degree rule and the rule of thirds; some basics of visual syntax, such as parallel and continuity editing, and one can learn or teach how to produce certain effects on screen, offer practical advice on operating a camera, placing lights, etc. Yet the mystery of the difference between why a particular shot works well and another, superficially similar shot does not, remains largely unscientific and subjective.

Filmmakers who have ventured to put into words how they created certain works tend to offer almost more spiritual and esoteric than practical advice, yet for the open mind ready to receive, such advice can radically re-wire one’s conception of image-making. Take for example Gregory Markopoulos’ assertion in ‘The Intuition Space’:

Theory: Time is a crystallization. A Universal particle: a particle in the long sentence which is the meaning of man.

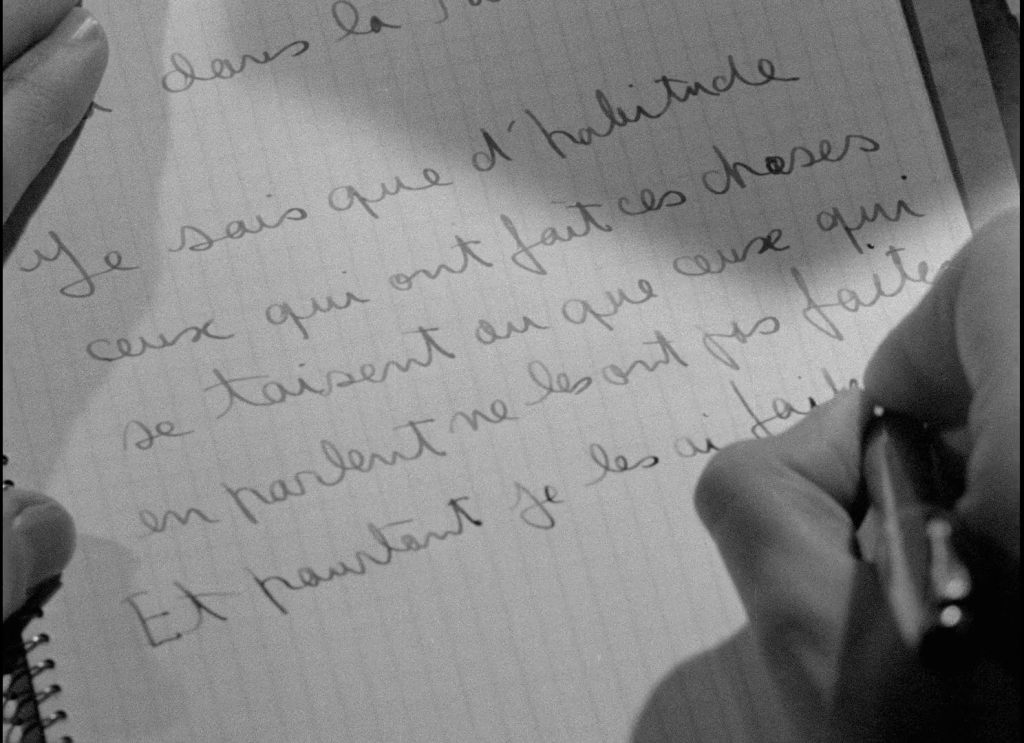

Or a selection from the countless one-offs of Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematograph:

Everything escapes and disperses. Continually bring it all back to one.

Or Lis Rhodes’ closing sentence from the essay ‘Noise of Memory’:

Despite the noise of memory, in the end, the necessity of movement will intervene—always.

I have always thought of filmmaking (or fiction prose, or musical composition, or painting, etc.) as its own kind of criticism—by choosing what to show (and how to show it), one engages in an affirmation or bucking of the norm. Thus, to write about what one has already made to a certain end could be difficult.

While there is no shortage of filmmakers who write or have written about film—their own films, critical writings about the work of others, or theoretical ideas demonstrated—those who forgo the esoteric in search of the concrete in their writing, there is a threat associated with self-analysis. As the critic Phil Coldiron recently mentioned, “Artists who write clearly about their work run a serious risk: that they will be taken at their word.”

Two of our essays focus on biographies outright. Cláudio Alves considers Ingmar Bergman’s The Magic Lantern, and all of its glaring omissions in regards to actual filmmaking: “Then I suddenly wrote twelve plays and an opera.” Ruairí McCann examines Josef ‘Jonas’ von Sternberg’s biography Fun in a Chinese Laundry, its irreverent name-calling, and its maverick author’s over-it attitude.

Instead of biography or film criticism, Luise Mörke has trained her sights on the prose fiction, specifically the short story ‘Making Love in 2003’, of director (and multimedia artist) Miranda July, examining the ways that it supplements her on-screen reach for an emotional core often dismissed as merely childish or quirky.

Ever the poet and philosopher, Michaël Van Remoortere contemplates Derek Jarman’s look at the beauty of living and coming to peace far from the cinema across several volumes. Taking this idea even further, Charlotte Wynant uses Chantal Akerman’s My Mother Laughs as a means of delving into the body, the self, and how one might reconcile either of these slippery and elusive ideas in the face of who we want to be and who we think others expect us to be.

These essays don’t contemplate texts in which filmmakers reveal their artistic ideas, but rather parse through what’s left unsaid and consider its meaning in tandem with their filmography. The goal of this issue is to look at the writing of filmmakers in the hopes not of unlocking hidden meaning in their film work, but understanding that an artist’s intentions with a work and the work itself are not a one to one ratio. That, just as a film, a filmmaker’s text must be actively read.