Kevin Brownlow was a guest at the University of Antwerp last week. He gave a charming and inspiring talk about his career in silent film at Cinema Zuid. Brownlow’s tireless efforts to encourage students to discover the excitement and wonder of silent cinema reminded me of one of my most cherished books by the British film historian: Mary Pickford Rediscovered, his homage to the first queen of the silent screen. Leafing through the book once more, got me to think about Mary Pickford’s career both in silent film and in film history in general.

Everyone who has seen Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994) probably remembers the scene in which infant vampire Claudia (Kirsten Dunst) tries to cut off her curls in an effort to shed her doll-like features. If you do, you’ll also remember Claudia’s devastation to discover that the curls grow immediately back, that she cannot escape her looks of innocence and youth, which are rather ill-suited to her vampire personality.

Mary Pickford probably would have wished the same thing to happen to her curls after the cutting of her own doll-like curls in the late twenties turned out to precipitate the end of her illustrious career. Like Claudia, Pickford felt that the curls were a burden to her as a performer and that they truncated her real abilities as an actress. Yet, despite the curls being gone audiences could not quite forget about them. They were gone but not forgotten and the bobbed Pickford no longer seemed to match anyone’s expectations or desire. (Husband Douglas Fairbanks is reported to have burst into tears. Pickford, curiously, felt both frightened by and enjoyed his response.)

Yet, the curl-cutting/curl-growing scene from Jordan’s picture fits Pickford’s case for another reason as well, for it appears that the legacy and reputation of Mary Pickford, once America’s and the World’s Sweetheart and Hollywood’s most powerful woman (person, really), is likewise bothered (cursed?) by an excess of ever-returning ‘curls.’ In Pickford’s case, the ‘curls’ represent a convolution of associations, stories, images and clichés about the actress, which work to obfuscate our impression of the quite multi-facetted Mary. The (capitalized) Curls stand for our notion of Pickford as a child-impersonator, as an icon of the sentimental sob story, as an ideal of womanhood très passé. In response to this, various historians, archivists and connoisseurs have tried to disclose Pickford to the world, metaphorically cutting of the ‘curls’ to reveal a subtler, more complex portrait of the actress. They have tried hard for us to rediscover Pickford as she once was to the world. But the Curls have proven quite obstinate, as we will see.

The first to discover Pickford was David Belasco, a theatre impresario who was nicknamed ‘the Bishop of Broadway.’ Belasco had had the honour of finding an angelic yet insistent little girl named Gladys Smith showing up in his office one day. As the story goes, eagerly repeated by the Broadway producer himself in a 1915 Photoplay article, Belasco immediately spotted her talent (and ambition) and engaged her for his successful plays (some stories add that it was he that rechristened her ‘Mary Pickford.’)

Pickford was discovered anew when she moved from stage to screen, where she worked for D.W. Griffith at American Mutoscope & Biograph. Her recognizable curls and quality of restrained acting were quickly noted by audiences and critics and she became a favourite first and later a true star, moving on to become America’s sweetheart and the queen of the movies in the course of the teens. By 1920 she was married to Hollywood’s favourite hunk – Fairbanks – and had started her own independent company – United Artists. Yet, as it would turn out, Belasco’s, Griffith’s and the world’s discovery almost became one of the lost souls of the silent screen, for already in the early thirties movie audiences and critics started to wonder what ever they had seen in her. And since her films were not available for renewed acquaintance they had no way to find out.

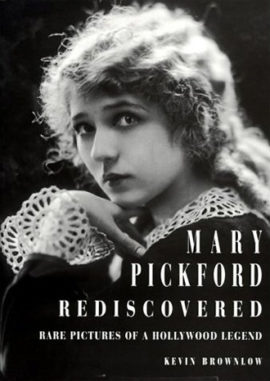

In 1999, Kevin Brownlow published Mary Pickford Rediscovered, a beautiful, lush collection of impossibly gorgeous photographs of a woman whose face had once been among the most recognizable in the world, accompanied by an insightful and generous reappraisal of her career. The book featured pictures ranging from behind the scenes production stills to personal photographs (often taken by the best still photographers of the day). Brownlow’s title made the breadth of his ambitions clear: to offer the chance to rediscover both the quality, versatility and importance of the star and her films. The book also served to revive the photographs themselves, which had been saved – painstakingly, suspensefully so – from a fate of untraceable dispersion and perhaps oblivion by the efforts of several film historians and archivists. (Among them the late Robert Cushman, archivist at Margaret Herrick Library, Joseph Yranski, David Sheppard and Brownlow himself.) A fascinating account of how much of the Pickford memorabilia almost did not make it to the Library of the Academy of Arts and Sciences can be found here.

Still one wonders why a woman like Pickford needed to be ‘rediscovered’ at all. Surely, I am not questioning Brownlow’s judgment here: Pickford indeed was in dire need of a rediscovery, but what I do wonder about is how she had become forgotten (and misunderstood) in the first place? And how she was overlooked for such a long time, even by, as Molly Haskell points out in her introduction to the most recent reappraisal of Pickford (Christel Schmidt’s Mary Pickford Queen of the Movies), ‘the staunch cinéphiles and feminists of the 70s’? If we look at those of Pickford’s contemporaries who can be said to have held similar positions of importance, relevance, fame, or popularity in their days, we find that Chaplin for example was never in want of (renewed) attention. Nor Keaton. Surely, Greta Garbo is not forgotten. Even Lillian Gish, the steely blonde muse of Griffith’s, is not quite forgotten (neither is Griffith for that matter). So why did it almost happen to Mary? Even if we disagree about the historical or aesthetic significance, cultural legacy or cinephiliac resonance of these individual personalities, no one would deny that Pickford’s achievements (from her role in the formation of the star system, her contributions to a new standard for modern film acting to the cofounding of United Artists) are beyond forgetting or overlooking, and thus demand to be rediscovered and written about. But let’s note that the term ‘rediscovery’ implies an explanation of what made her so important (even though that would seem to be quite obvious) and usually a rediscovery includes some sort of an apology for liking her. Brownlow for example acknowledges that Pickford is hard to sell to those who know her from her most popular films like The Poor Little Rich Girl or Little Annie Rooney (for an example, he cites his wife who also dislikes John Ford’s Irish films). Film scholar Gaylyn Studlar, in her essay on Pickford, ties the actress to a cultural gaze that to modern viewers can only be described as ‘paedophilic,’ reflecting unsettling and suspect sexual desires and uncomfortable notions of ‘ideal’ womanhood. So for reasons personal or cultural, we could have our reasons to be squeamish of this woman, but are they warranted?

Jeanine Basinger, whose Silent Stars (also from 1999) celebrates ‘a group of silent stars who are somehow forgotten, misunderstood or underappreciated,’ placed Pickford at the front. (But the cover went to Pola Negri.) The other rediscovered stars in the book, among which are the Talmadge sisters, Mabel Normand, Gloria Swanson and Negri, and Rin-Tin-Tin, were not of the stature of Pickford (Douglas Fairbanks who also features excepted I guess,), and it is odd to find Pickford in the line-up at all, as Basinger acknowledges. Yet she was selected, Basinger tells us, because it is rather ‘ironic that the biggest female star in history ends up being the most misunderstood.’ And here ‘misunderstood’ surely also implies a certain dislike. Basinger’s book is the work of a cinephile, guided but not biased by personal taste and amusement, curiosity, and enchantment. It is also excellent scholarship and a great read and it argues quite forcibly that there is a lot to like about the golden curled icon.

There had been previous attempts to rediscover Pickford of course. Two passionate texts on Pickford immediately come to mind, texts that tried to save Pickford from oblivion or from the well-worn stories about her (child impersonator! Sentimental! No friend of Charlie’s!). One was by Edward Wagenknecht (a chapter in his nostalgic Movies in the Age of Innocence from1962 recalling his childhood at the silent movies, an endeavour that to the author feels like ‘living my life over again’) and the other by James Card (in Image in 1959). It’s clear that Wagenknecht and especially Card tried to salvage Pickford from the maelstrom of oblivion and underappreciation that was to befall her (in part perhaps self-inflicted because she made the availability of good prints or her films rather rare).

James Card cites Iris Barry who asserted in 1926 that: ‘The two greatest names in the cinema are, I beg to reiterate, Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin . . . theirs are the greatest names in the cinema and from an historical point of view they always will be great.’ Yet, in the years that followed Barry’s assertion, Pickford’s status would change radically. Just four years later Paul Rotha already disparaged: ‘As of Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks I find difficulty in writing, for there is a consciousness of vagueness, an indefinable emotion as to her precise degree of accomplishment.’ Reducing Pickford to Mrs. Fairbanks… well, it was the first step in forgetting about her and her achievements.

James Card’s text focuses on the films as he tries to convince the sceptics to actually look at the films instead on being put off by vague reminiscences or blatant misconceptions. Card realizes that although Pickford has not been exactly omitted in critics’ or historians’ texts and overviews, most of them are unfamiliar with her films, which leads to further uninformed representation. Card complains: ‘Either out of some respect for Miss Pickford’s unassailable position as one of the cinema greats, or out of praise-worthy caution in view of their not having seen her films, many writers only circuitously imply that the Pickford performances were the epitome of saccharine banality, sweetness and light and all permeated with the philosophy of Pollyanna.’ But further implication was all her shaky reputation needed and Card was adamant to solve this in the best way he saw fit: by showing her films repeatedly to audiences of the Dryden Theatre of Eastman House. ‘The best part of the rediscovery of the Pickford films is that the measure of their greatness does not depend upon the isolated opinions of a few connoisseurs nor, worse, upon the cherished preciousness of the cultist’s infatuation,‘ he notes. So, thanks to Card’s efforts, the people in Rochester rediscovered Pickford for themselves in the early sixties. But what about the rest of the world?

Some of them may have rediscovered Pickford through Edward Wagenknecht’s beautiful evocation in his evocative and nostalgic Movies in the Age of Innocence(1962). Like, certain critics (Rotha for example), Wagenknecht also admits to a certain ‘difficulty’ in writing about her (‘her films encourage, and submit to, little analysis’) but he does not imply this is the result of questionable accomplishment as others did. Instead he places her firmly in an ‘age of innocence,’ pointing out that Pickford’s films and her role in them invite an enthrallment and strong emotional appeal that despite being difficult to put into words are valuable and significant. If anything, Wagenknecht would have put the blame with himself for his inability to praise and appraise her adequately.

At the time of Pickford’s death in 1971, she was eulogized and discussed quite aptly by Andrew Sarris (who stressed her working class appeal), but she was also covered (uncovered) quite subtly by Alexander Walker, who realized like Card before him that the best way to deal with Pickford was not by relying on fans’ memories but by actually looking at her films. If anything, the fond reminiscences of her fans would likely impress the Pickford neophyte (unfamiliar with the movies themselves) with that unwelcome idea of saccharine sentimentality that made her so suspect to modern tastes.

In the nineties, Pickford’s extraordinary life was done justice with two excellent biographies, one by Scott Eyman in 1990 and the other by Eileen Whitfield (1997), and Pickford featured prominently in Carrie Beauchamp’s biography of scenario writer Frances Marion, who wrote at least thirteen scripts for Pickford in the second half of the teens. These books were an excellent addition to Pickford’s own disappointing (too short) biography Sunshine and Shadow (1955) and a thin booklet by Robert Windeler (1975).

Christel Schmidt has edited the most recent book on Pickford, which again explains its relevance by pointing to the ways in which the star is still greatly misunderstood and misrepresented, and to the limited scholarship devoted to her. The book sheds light on Pickford’s many activities, qualities, and charms, and includes a focus on both well-trodden paths (her child impersonations, the curls, her marriage) as well as on areas that have received little attention (her costumes, Pickford’s relation to race). Schmidt’s own research is supported by work from Pickford biographer Eileen Whitfield, Kevin Brownlow, and reprints from Edward Wagenknecht and James Card. Pickford devotees like myself will gobble it up, but I still wonder whether this book will change the wretched misconception that despite recent efforts (of Brownlow’s, Basinger’s, Whitfield’s…) has persisted. The book is another rediscovery of Pickford’s and points the way to a different knowledge and assessment of film history, a hope of discovering Pickford again as once such large audiences did but, as in the story of the curls, how long will she stay in sight, how long before we settle back for the often-told story of the child impersonator whose pictures ridiculously and uncomfortably remind us of the rather quaint and slightly naive filmmaking of long ago?

If someone like Pickford is still in need of rediscovery every few years, what about that legion of other important, game changing, influential stars of the silent era? As research of recent years has shown, there is in fact a lot to be (re)discovered, dusted off in the archives and presented and reinterpreted, but in counterbalance to all this excitement, should we not, as Jane Gaines has argued, be a little wary, of so many discoveries, so many lost objects to cherish and perhaps overcook in our corrected film histories? Aren’t we, in our efforts to unveil, recover or restore forgotten (lost) stars or chapters in film history likely to overwrite other parts or threads? And aren’t we writing in invisible ink for the most part, because misremembered and oddly neglected figures such as Pickford are never really rediscovered (because they were never completely off the radar) and what is presented as new about them quickly rubs off in favour of what we already knew (or think we knew) about them anyway. Or as Alexander Walker noted: ’people generally remember not what they see on the screen, but what they wish to remember – and this, in turn, dictates what they wish to see.’ So truly rediscovering Pickford would appear to be a lost cause, because we are not really looking to find her.