[editor’s note: this text was written before Angès Varda passed away]

Varda par Agnès was the name of a book of thoughts and anecdotes mixed with photography, published by the Belgian-born French filmmaker in 1994. Now, in 2019, she gave the same title to her newest film, a meta-exploration of her work in photography, cinema, and visual art to date, which comes close to what can be described as a masterclass. The film’s opening credits roll, written in blue, pastel pink and yellow, over blurred stills and sequences from her films, whose graininess bears testament to time past. In a colour scheme recalling Le bonheur’s (1965) vibrant opening, the journey into the world of Agnès Varda begins.

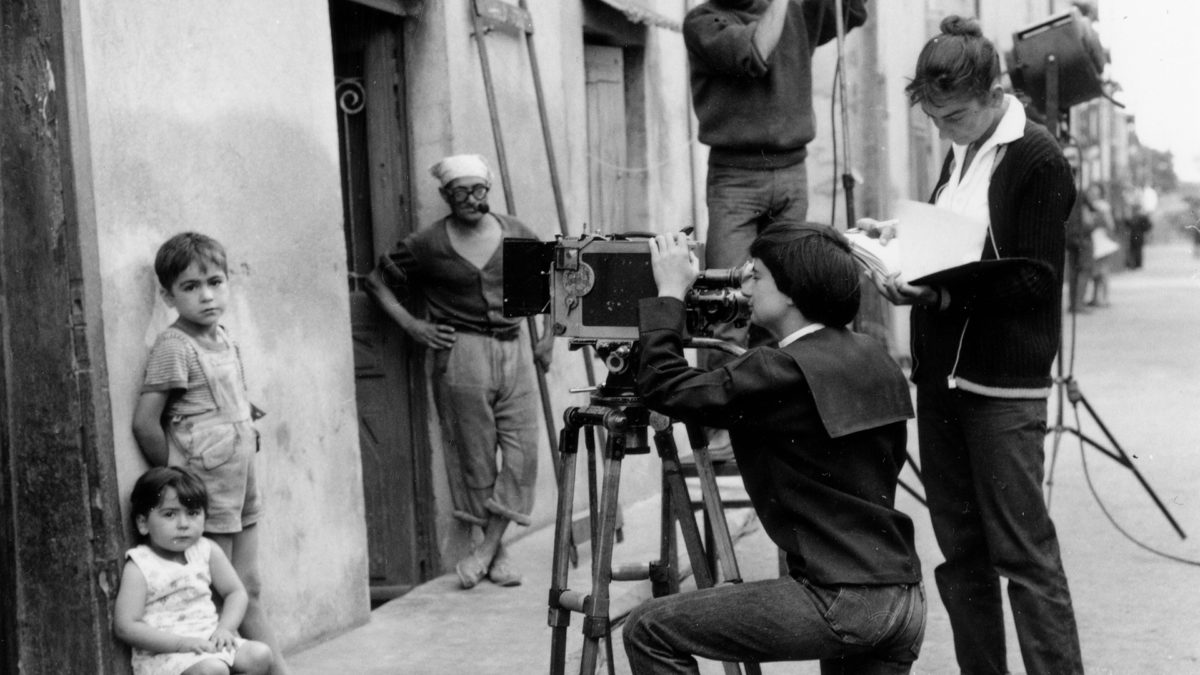

Like Varda’s artistic life, the film takes place in two different centuries; therefore, it is split in two parts. While the beginning covers the years between 1954 and 2000, the second part is set in the new millennium. The film is structured loosely around a talk Varda gives in a sold-out Paris Opera House, under the spectacular spotlights of this history-laden place in which one can step back from cinema and yet plunge deep into its essence. She shares the main tenets of her filmmaking: inspiration, creation, and sharing. Inspiration, she explains from the old-fashioned director’s chair that’s seen in the Opera and on a beach later on, is the kindling of a film—a combustive combination of motivation and the fluid material of ideas that pushes a film from the realm of thought and potentiality to that of actual existence. This actualization is creation: the way the film will be aesthetically assembled—with a strong or free-floating structure, in colour or black and white, etc.—, in Varda’s book, is the labour the filmmaker has to deliver in order to bring the film into reality. Yet, as she states numerous times, cinema exists on the fringes of the real; Varda’s films blend documentary and fiction, her fiction features accommodating elements of documented, unrendered life. Her favourite example is to be found in Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962), an exploration of inner life and what she calls “subjective time”, in a sequence where Cléo walks through the streets of Paris, unstaged daily life all around her. Fictional filmmaking set in a real place and time can play with the amazement of random passers-by and street performers, people who have become a part of Cléo’s world without even suspecting—the magic of the nouvelle vague was bringing cameras out on the streets of Paris.

Reading between the lines of Agnès Varda’s films from that period, starting with her debut La Pointe-Courte (1955), the possible precursor to the nouvelle vague set in the eponymous fishing village in south of France, one can find a subtle love letter to reality. As she recounts the process of filming, the people behind the faces appear more important to her than the film’s subsequent fame. In a sequence from Les plages d’Agnès (2008), the sons of a cast member participate in a procession that replicates once lost but now found footage of their father during the making of the film—the two men push a carriage that also serves as a film screen for the projected reel. At the same time, Varda shows much affection for both Silvia Monfort and Philippe Noiret, the stars of La Pointe-Courte, whom she knew from the Théâtre national populaire where she worked as a photographer. She tenderly recalls her days as a theatre photographer, being close to acting titans in their Shakespearean roles; a slideshow of her photos expresses the adoration and respect she held for these thespians. For her, the blurred line between documentary and fiction is reflected in the way she films people—with love and empathy.

No setting other than the filled to capacity Paris Opera could be more suited to encompass her devotion to art in all its richness, blurring the line between stage and audience, the abstraction of her talk interacting with the real faces of the audience, as the camera cuts from one to the other. It is no surprise that her previous film, Visages villages (2017), a collaboration with French mural artist JR, focuses on the existence of places in relation to individuals, real humans with their idiosyncratic personalities. A similar paean to humanity resonates through Varda par Agnès, which brings the filmmaker even closer to her audience in a retrospective, while revisiting the past of important people in Varda’s career and personal life. Sharing is the third, indispensable element in her filmmaking ‘guide’. “You make a film to show it”, she explains. For her, the meeting between filmmaking and the audience is “a perfect example of a miracle”.

Reaching out to the Other, forming an affectionate bond between filmmaker and spectator as if in intimate conversation, characterises her late documentary work, yet in the beginning of her career, she travelled to Cuba to document the revolution (Salut les Cubains, 1971), bore witness to The Black Panthers’ activism (Black Panthers, 1968), shot the hippy-themed American production Lions Love (1969), and even captured feminism in song in Réponse de femmes (1975). Parallel to these topical works, she filmed herself meeting a relative she didn’t know she had, on a fishing boat on the outskirts of San Francisco, in Uncle Yanco (1967). Encounters, both of groups and individuals, are life-affirming for Agnès Varda; no one is really a stranger, more like a part of a family you didn’t know you had before.

In the second part of Varda par Agnès, she leaves the opera stage to go to her favourite place: the beach. Amidst cardboard figures of birds, seated in her “Varda”-branded chair, she exclaims: “An empty cinema!” Her indispensable sense of humour recapitulates decades of cinephilia and a lifetime spent with filmmaking (she insists she was a photographer in her first life), founded on a stoic attitude towards the truth of cinema. Sandrine Bonnaire, once the fragile 17-year-old star of Varda’s award-winning Sans toit ni loi (1985), joins her on the sun-drenched beach under the shade of an umbrella, to discuss her role of almost forty years ago. A touching episode unfolds when Bonnaire recalls the blisters she had on her hands from playing the homeless Mona, to which Varda jokingly yet vulnerably replies that “she should have licked them”. A life in service of cinema demands sacrifices, and Varda concedes that cinema can, in that sense, be very humbling. With the same spicy humour she later recounts how she brought in Mr. Stardom, Robert De Niro, for the shooting of her comedic take on film history, Les cent et une nuits de Simon Cinéma (1995), to star alongside Catherine Deneuve. Laughing, she deconstructs a romantic scene where both ride on a boat. In real life, the lake was a pond, Robert De Niro learned his lines on the plane there, and he managed to fall in the water. Later on, she discloses the logistics behind the 13 unorthodox tracking shots she used to show Mona’s journey in Sans toit ni loi, by riding in a cart on tracks herself, passing the frames as they form a continuous panorama from right to left. She addresses the illusion of continuity and of fictional worlds in such playful ways, almost as if the sequence were a ‘behind the scenes’ spoof. This becomes a metaphor for the whole of Varda par Agnès itself, a deconstruction that elucidates not the technical decisions, but the magic that is interwoven between the frames, binding them into an inseparable unity. Laying bare the anatomy of a work of art has never been so gentle.

In a way, Varda sees her artistic life as a prelude, although that wasn’t the case in 2008 when Les plages d’Agnès was released, which she confesses took a toll on her, approaching her 80th anniversary. Now, ten years later, as she is 90 years old, it seems that age anxiety is not an issue anymore. Varda par Agnès is already rumoured to be her ‘swan song’, her final film in a long career as a visual artist. At the same time, the question of an ending is an indefinite one. Her new film is a comma, masked as a full stop by being past-oriented, saturated with intention, motivation, love, and remembrance; a work of memory, a memoir that has material objects to cling to—be it film, photographs, or installations. Faced with declining sight, Varda is able to see less and less of the world, which is why she wants to film it more and more; faces come to the forefront. Les plages d’Agnès might have been a similar exercise of remembering the past, but now Varda par Agnès is immortalising that act. Rather than reiterating the past, the films and talks revisited afresh now whisper the word “eternity”.

As the awards that both she and Jacques Demy won are shown buried in the sand of her favourite beaches, Varda whispers, “vanitas vanitatum…” Calling out the sin of vanity to strip away her own fame, she shows that the very aim of this new film is not her self-glorification, nor a simple retrospective, but a coming to terms with time’s passing. Just like the heart-shaped potatoes of her installation Patatutopia in the Venice Biennale 2003, the process of aging reveals beauty that was impossible to be seen before. Extending from the ageless art of cinema to the ageing of potato sprouts, the miracles of Agnès Varda’s vision point to a new way of seeing: seeing by gleaning, seeing through houses literally made from cinema (her Cinema Shacks built out of 35mm film)… All of it, a cine-writing (ciné-éctriture) signed Agnès Varda, a life’s work that is humanistic, empathetic, and more real than documentary and fiction put together.