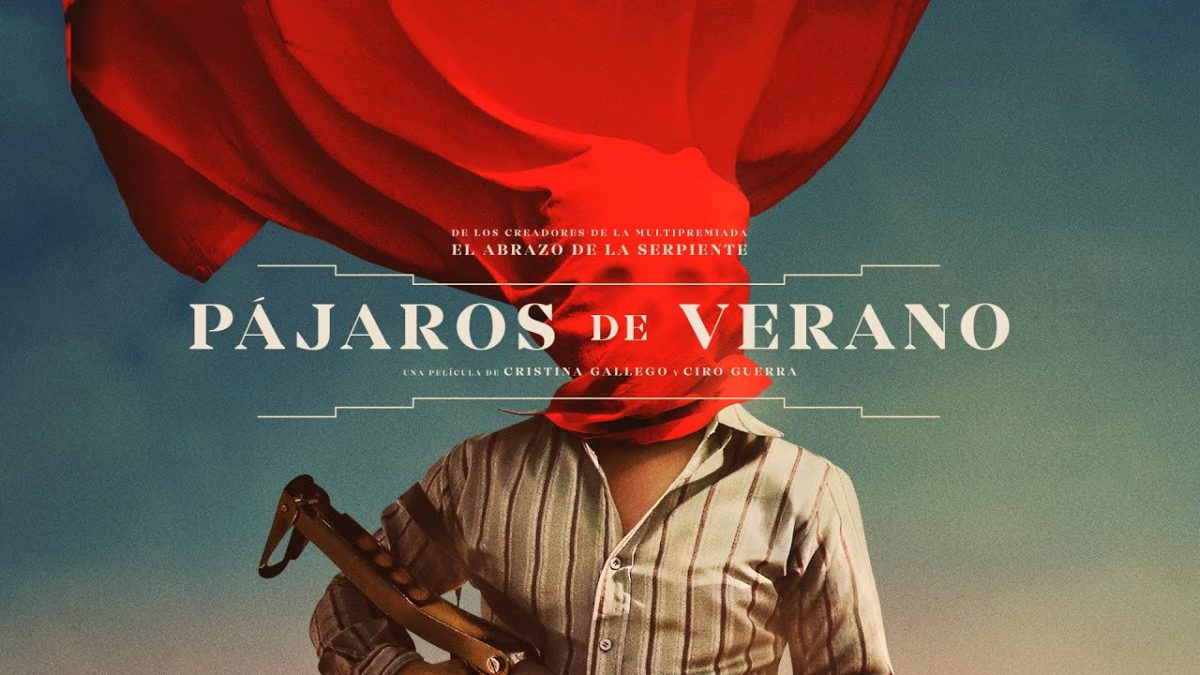

In 2015, the Colombian director Cristina Gallego collaborated with fellow filmmaker Ciro Guerra on El abrazo de la serpiente (2015), a film that was very well received internationally, won several awards—among them top prices at the Rotterdam and Cannes film festivals—and ended up being nominated for the Academy Awards in the ‘Best Foreign Language Film’ category. Three years later, the duo shares the directing honors for the powerful Pájaros de verano (2018) (internationally released as Birds of Passage). The movie serves as an intoxicatingly beautiful celebration of endemic cultural tropes, recalling the films of Pasolini and Parajanov in the way the rituals and local culture are embedded into the film’s narrative and formal language. Gallego and Guerra manage to merge a transcultural sense of classic tragedy with imagery that is dominated by the local landscapes and that rivals the pictorial quality of a John Ford western.

While the Peace Corps has taken issue with the way their volunteers are portrayed (buying and selling weed), the movie—while being critically lauded generally—has mainly been accused of being guilty of a latent ‘exoticism’ in the way it portrays the local Wayúu culture. These accusations fail to take a broader anthropological point of view into account and misinterpret Cristina Gallego’s statement that the use of the Wayúu culture made it easier to display the transformation of a traditional society. This process of cultural hybridization the director refers to is a deeper laying narrative that I believe serves as the true thematic core of Pájaros de verano.

Local Traditions and Cultural Hybridization

From the very first seconds onwards—a deep, primal display of sensuous colors—Pájaros de verano manifests itself as a movie possessing a forceful visual splendor. Its narrative underpinnings owe much to local elements, being anchored in the local endemic Wayúu culture in much the same vein as the literary masterpiece Cien anõs de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967) by the Nobel prize winning Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez. As was the case in the work of the celebrated author, the Wayúu traditions and communal structures are firmly embedded into the movie’s core—both thematically and visually.

The film starts with the ritual that guides the young local girl Zaida from childhood into womanhood, allowing her to be courted by the dashing youngster Rapayet. Rapayet’s marriage proposal is met by the request for a nigh unobtainable bridewealth. His quest to gather these riches sends him on a path towards drug trade and crime that will eventually lead to the small commune’s utter destruction. This prologue—the rest of the film is divided into five ‘chants’ by a local narrator—offers a powerful and enchanting initial view of the traditions and rituals that will dominate the story. Contrary to the objections raised by some critics, Pájaros de verano is a film that deals with the hybridization of local traditions and in no way attempts to link the story to actual local history (the only link is the statement that the relation between Wayúu heritage and the world at large has deeply transformed the former’s identity). It is this process of hybridization that serves as the real thematic core of the movie, as Gallego tries to convey in her statement about the use of the Wayúu culture.

As with every evolving contact between local traditions and a larger outside world, the interaction between the two entities changes both sides. However, the dominant cultural hegemony of the western world (a broad generalization I’m using here to convey the idea of a ‘cultura franca’ dominated by late capitalist values that run counter to those of most small local communities which harbor systems that are not based on the maximization of profit) painlessly appropriates and absorbs elements it encounters, while the absorbed party is usually drastically transformed when these different systems of authority, belief and stratification clash.

Witchcraft and Witches

A well-known African exampleThis chapter owes a lot to the research of anthropologist Prof. Koenraad Stroeken (University of Ghent).—while stemming from a different continent—is emblematic for the way this process of hybridization functions. African societies have always fostered the concept of ‘witchcraft’ and ‘witches’ living among the villagers. In the last two decades, media coverage has emphasized the fact that this ancient so-called superstition leads to violence, when persons are murdered if they are believed to be witches. What most of these writers fail to mention is that only in the second half of the twentieth century, the practice of murdering and physically punishing ‘witches’, has gained a foothold in African society.

The original concept of witchcraft demanded no such sanction and was never about exiling or punishing those who were believed to be witches. One of the most enduring canonical anthropological texts on this subject matter is still Evans-Pritchard’s 1937 Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande. Offering an in-depth look at the concept of witchcraft within Azande society, it also serves as a warning to western readers, not to confuse the Judean-Christian concept of witches that was upheld mostly during the European Middle Ages with the African idea of witchcraft. “Witchcraft is not an objective reality” the author states, clearly delineating the concept of witchcraft that can be found throughout Africa: witches and witchcraft are tied to ideas of guilt and a person who has certain leverage over you (in some societies even the guilt burden of marrying someone and separating them from their family is tied to the idea of a witch in the spouse’s family that haunts you). Knowing who that witch is—a task usually reserved for the medicine man—is enough to break the spell and liberate the haunted. This concept runs through every idea about witchcraft: there is no direct causal link for things that are believed to be witchcraft, a concept that is alien to our western culture that is dominated by ideas of cause and effect. This concept however is at the heart of African ideas about witchcraft and demands no such thing as punishment or retribution.

It is only when these traditions met new concepts about guilt and punishment, that the core of the rituals and traditions was altered and evolved into the violent mutations that run rampant in African societies nowadays. When the western view of justice was introduced in African society, it started to alter the existing concept of witchcraft. Gradually it was no longer satisfactory to have knowledge about the identity of your ‘witch’, but it became necessary to retaliate against the witch (crime deserves punishment, as the locals learned the harsh way), thus giving rise to a culture of violence that started to become associated with the concept of witchcraft. Journalists covering this topic often refer to these practices as being ‘embedded within the ancient customs of African societies’, neglecting the fact that they are actually addressing very recent and new incarnations of these practices, that have drifted further and further away from the role they once had within their native social groups. Similar processes of hybridization through contact or ‘contamination’ are also addressed in the context of the colonization of India in Arjun Apadurai’s book Modernity at Large (1996), director Djibril Diop Mambéty’s masterful Hyènes (1992) or in the upcoming documentary Sakawa (2018).

This hybridization process is also at the heart of Pájaros de verano. Just like the traditional role of the ‘witch’ was transformed when an external system of ‘guilt and punishment’ was introduced to the concept and paved the way for a mutation dominated by retaliation and revenge, Pájaros de verano also illustrates how local traditions were appropriated into a world, system and society in which they were never meant to function, thus giving rise to travesties that lead to violence and decline.

The most striking example in the film is the idea of the neutral ‘messenger’, someone who is to be respected and honored and whose neutral position can never be questioned or violated. The destruction of this symbol leads the characters in the film down an unstoppable spiral of violence and carnage, exactly because this traditional figure is introduced into a world that adheres to completely different rules and a different logic, in which the ‘messenger’ is nothing but a sad and almost laughable relic, helplessly clinging to a tradition that no longer exists in the new reality.

That new reality starts to form when anno 1968 Rapayet turns to selling a shipment of marihuana to a few Americans, in order to gather the necessary means to pay for his bridewealth. His gamble pays off and after marrying he decides to continue his criminal partnership with a friend and one of his uncles, who supplies the weed plants he harvests at his ranch.

The success of the illegal trade comes with changes within the small community, introduced to us through ingenious visual metaphors: the harsh, penetrating lights of the expensive Jeep that is paid for with drug money and that disturbs the slumber of the small village in the dead of night; or later in the posh postmodern house Rapayet builds for his family (reminiscent of the work of the Mexican architect Luis Barragán) and that dominates its desert surroundings in a most intimidating way. The exchange of gifts that we witness at the start of the film evolves into the exchange of weapons, further contaminating local traditions and eventually leading down a path that destroys the whole family and the small community. This destruction is grounded in the fact that a set of traditions and endemic rules that grew out of an ancient local culture and that was shaped by this culture, is no longer functional within the new reality that grows out of Rapayet’s drug trade. As with the African example, two non-compatible systems, built on completely different conceptions of the world and communal experience, are combined and mutate into new incarnations of the local traditions, which are no longer apt at dealing with a world they were never meant for. It is this process of hybridization that steers Pájaros de verano’s narrative and that seems to elude most critics when they claim the directors exploit the Wayúu culture.

Transcultural Narrative Forms

The concept of the family as a business (in the world of crime or otherwise), the link with local traditions and the structural form of a family chronicle that Gallego and Guerra employ, are obviously reminiscent of Marquèz’s work, but also bring to mind The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) or its Indian counterpart, Anurag Kashyap’s five hour epic Gangs of Wasseypur (2012). Referencing this broader transcultural context strengthens Pájaros de verano’s tragic power.

When Michael J. Witzel set out to chart the genealogy of the world’s oldest narratives in The Origins of the World’s Mythologies (2013), he proved that certain tales about the evolution of local groups and families have existed throughout the history of all the world’s narrative traditions. As Torben Grodal has stated, there are also neurobiological underpinnings for the endurance of certain types of storytelling devices and the worldwide spread of cinema has latched onto these tropes from the very beginning of its conception as a worldwide medium.

Not only is the narrative structure of Pájaros de verano entrenched in a transcultural (movie) tradition, the same holds true for its visual language, that owes as much to the local landscape as to the American ‘western’ tradition. As much as it is impossible not to ponder Pájaros de verano’s narrative as part of a larger set of tales about the evolution of groups and traditions, it is equally impossible to ignore the visual heritage of the western that runs through its pictorial veins. This visual language and the broader cultural context seamlessly merge with the ideas about local traditions and their new forms that are the core of the film, and precisely this merging is Pájaros de verano’s greatest cinematic strength.