A languid city symphony fashioned as an idyllic Georgian folktale. Aleksandre Koberidze’s sophomore feature, What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?, operates as a carte blanche carnival of obtuse situations among slight variations of the familiar. All individual elements of the film acquiesce to a tonal levity, threaded through the runtime by a narrator whose disposition flows with paternal warmth. Playful convalescence between the strange and the mundane ebb and flow with symbiotic rapport. Local canine soccer fanatics as petty as any two-legged schmuck. Delicious soft serve ice cream at a cafe! Sentient street intersections warning of the Evil eye in the wake of a fervently amorous meet-cute. Consume six cookies in under a minute and win a cash prize! Reconciling an irreversible physiognomic reconfiguration overnight. The World Cup! Everything is gravy as long as you’re able to avoid the Evil eye… and even then, a cast curse is merely a detour, not calamity; no matter what, you’re golden.

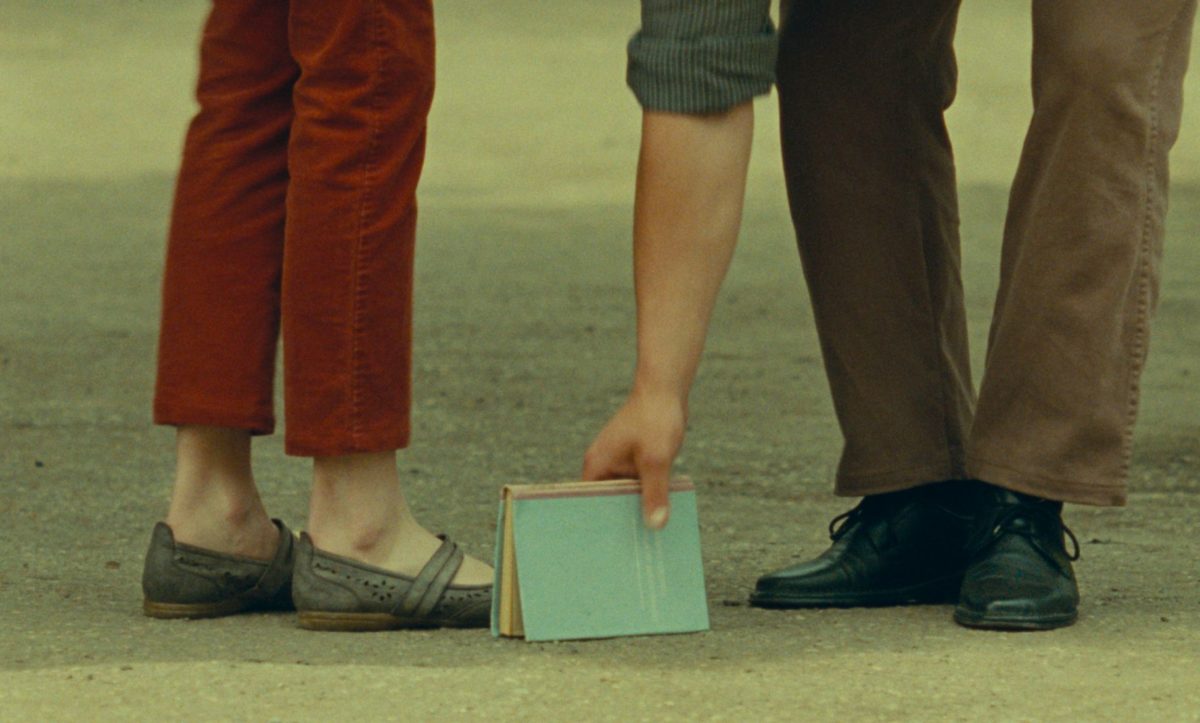

The film opens with an adorable fumbling of apologetic exchanges between Lisa (Ani Karseladze) and Giorgi (Giorgi Bochorishvili) as thrice they bump into each other (in the span of minutes) while traveling to their respective professions; Lisa a pharmacist and Georgi a soccer player. By the third run-in with each other, the expression “love at first sight” does occur, but Koberidze recontextualizes cliché through framing the camera at ground level to where only their lowers halves show. Withholding the countenance of the love’s conception foreshadows who we are and aren’t supposed to get familiar with. Uncharacteristic initiative sets a date at a cafe for the following day. As Lisa crosses an intersection walking home that night, a seedling, a street security camera and a rain gutter warn her, per the narrator, of an ill intent to cast an Evil eye on her, cursing her. She is informed that before the time of her date tomorrow she will experience a change to her physical appearance that renders her unrecognizable. Lisa is naturally skeptical, if not unconcerned; whether she wakes up appearing as a different person or not is irrelevant—if that’s the case she’ll simply explain what happened to Giorgi. The curse affects both of them, causing each to be unable to recognize the other at the cafe. Instead of instinctive horror at their new appearance, indignant refusal of being stood up grips Lisa and Georgi. Obsolescence of the physical form is perfectly within reason when concerning matters of the heart; bodies merely function as conduits for emotional Nirvana and if that manifests as a swap, so be it, not a second thought. Initially the couple feel like the center of the film but a fourth of the way in they actually settle into somewhat of a synecdoche for the city’s buoyant wavelength of the fantastic. Koberidze acclimates the viewer by way of the couple, insuring any potential for refusal to meet the film on its own terms is alleviated. The love involved here is too transcendent to deny—as Proust posits: “Love, even in its humblest beginnings, is a striking example of how little reality means to us.”

They both immediately abandon their careers and accept positions at the cafe where the date was set, each convinced that the other will eventually show up. The film blithely wanders off from the couple, as the world’s only international sport begins its biggest event. Koberidze’s pacing, courtesy of cutting the film primarily to the rhythm of shimmering, symphonic leitmotifs, gives the impression of a lacked urgency to arrive anywhere narratively. The soccer game’s on, what’s the rush? The 150-minute run time runs the risk of feeling arduous until you realize it’s by design, to provide all the space necessary for whoever needs it. The country side setting dresses the town with an anachronistic quality utterly untouched by modernity, and all of the headache that comes with it, i.e. capitalism. Koberidze constantly reinforces the idea that personal wellness determines the labor, or lack thereof, not the other way around. The idea only seems radical in a real-world space, but inside of DP Faraz Fesharaki’s sun dappled 16 mm textures, dripping in golden hour maximalism—the kind that would have Pooh Bear in a honey hangover for weeks—it only feels appropriate.

The title of the film is a question of relativity, an enormously blank canvas every person on the planet has to share. The sky is ephemeral the same way the physical form is for Lisa and Georgi; a projection of whatever a person’s needs may be at any given time. A hierarchy is absent among what abates our anxieties. The couple’s story is certainly present, but the linearity is optional, elastic. Having some ice cream, finding your way to your soulmate—what’s the difference?